|

There are 20 musical references in the script for Julius Caesar, 17 of which are diagetic stage directions:

Most common in Shakespeare's histories, the term alarum signals danger (an alarm), especially in the context of combat, that is often but not always musical in nature. Plenty of musical alarums exist in Shakespeare's stage directions, but plenty of not-necessarily-musical examples exist as well. In their exhaustive Music in Shakespeare: A Dictionary, Christopher R. Wilson and Michela Calore write, “The sounding of alarums by various instruments, especially trumpets, drums or bells is connected with military atmospheres” (p. 12). In Caesar, the term only appears in act 5, as the two armies battle. On the other hand, flourish indicates the entrance/departure of the most important characters. In the histories it typically designates royalty, but in Caesar it signals the title character, Brutus, and the soothsayer. Some confusion exists as to flourish instrumentation. Wilson and Calore write oxymoronically, “the flourish was invariably for trumpets or cornetts sometimes accompanied by drums. Some examples of flourishes for recorders and hautboys are also observed. In general, any instrument or instruments could play a flourish as a short (improvised) warm-up to a longer notated piece” (p. 179). Regardless, flourishes were “the most improvisatory and musically least structured” stage direction (p. 179). Edward Naylor, in his book Shakespeare and Music cites 68 instances of the term “flourish” as a stage direction in 17 of Shakespeare's plays: 22 for the entrance/exit of royalty, 12 for the entrance/exit of important non-royalty, 10 for the public welcoming of royalty or otherwise important characters, 7 to conclude a scene, 6 to indicate victory in battle, 2 to announce royal decrees, 2 to indicate entrance/exit of a governmental body (senate, tribune), and 2 to signal the approach of a play-within-the-play (p. 161). (How come that only totals 63?) “The most exclusive, least used signal in military and courtly contexts”, a sennet is similar to a flourish, but more standardized (less improvisatory) and longer in duration (Wilson and Calore, p. 376). According to Naylor, “sennet” occurs only 9 times in 8 plays – 3 to designate the entrace/exit of a Parliament, 3 for a royal procession, and 3 to signal the presence of royalty (p. 172). So there appears to be no set definition for these terms, only general patterns in their usage. It should also be noted that there is much debate whether or not Shakespeare actually wrote his own stage directions, or if they were added subsequently by editors. We will probably never know for sure, one way or the other. While most musical references in Caesar are stage directions and thus aren't necessarily Shakespeare's words, there are three other musical references scattered throughout the script that (presumably) did come from his pen:

While much music based on Julius Caesar exists, little of it bears any resemblance to Shakespeare's play. Georg Frederic Handel's Giulio Cesare, for instance, is the best-known and most frequently-performed, yet has nothing to do with Shakespeare.

Robert Schumann's 1851 Julius Caesar Overture, Op. 128 bears little resemblance to Shakespeare's play, either, though it was apparently inspired by it. In his essay 'Shakespeare in the Concert Hall', Roger Fiske articulates and addresses a two-fold challenge of programmatic music: On one hand, the composer is limited by the narrative functions s/he is supplementing; on the other, the composer must write compelling music, independent of any narrative connotations. “Only when a composer fails at both levels,” he writes, “as Schumann did in his overture to Julius Caesar, is descriptive music best left on the shelf” (p. 181). Ouch! Orson Welles famously spearheaded a 1937 production of Caesar with the Mercury Theater, featuring music by Mark Blitzstein. That production was adapted for a 11 September 1938 radio broadcast, retaining Blitzstein's score, which is available on Amazon for just $0.69. (The description falsely cites Bernard Herrmann, but the broadcast correctly credits Blitzstein.) Miklós Rózsa composed the score for a 1953 film adaptation of Shakespeare, directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz. Its entire soundtrack can be heard on YouTube. Giselher Klebe wrote a brief dodecaphonic opera titled Die Ermordung Cäsars [The Murder of Caesar], Op. 32 in 1959, with a libretto by August Wilhelm von Schlegel based on Shakespeare. In his essay 'Shakespeare and Opera', Winton Dean describes this work as “a projection of the moral disintegration of the Roman people, suggested perhaps by the collapse of the Nazi regime in Germany. Everything is concentrated on creating an impression of growing chaos” (p. 155). Winton Dean, Dorothy Moore, and Phyllis Hartnoll's 'Catalogue of Music Works Based on the Plays and Poetry of Shakespeare' also lists the following, which I have annotated, though I've been unable to find any further information:

Curiously, several songs from the pop world relate to Shakespeare's play. Phish's 1994 'Julius' draws on Shakespeare's account, according to The Phish Companion: A Guide to the Band and Their Music. The American rock band The Ides of March (of 'Vehicle' fame) is a direct reference to Shakespeare, stemming from their bassist, Bob Bergland, who read Julius Caesar in high school. There are also several pop recordings based on the ancient Roman dictator that might or might not relate to Shakespeare's play:

0 Comments

The 472-mile drive took 11 hours and 36 minutes, including stops. On March 7, I arrived back home in Indianapolis following a brief but grueling lecture tour through Illinois and Missouri in which I delivered seven presentations in four days. To keep me company through the endless rural landscapes of Interstate 70, I downloaded Jillian Keenan's 2016 memoir SEX WITH SHAKESPEARE. I'm not entirely sure why I chose that title – I've never been a fan of Shakespeare (I can't say the same for sex!), but I've always felt like I should be. So, having only the slightest idea what Keenan's book was actually about, I hit play as I left Kansas City, and the 10-hour audiobook concluded just before pulling into my garage. In short, SEX WITH SHAKESPEARE is Keenan's realization that she's a spanking fetishist, and how Shakespeare assisted her self-acceptance. “If I could find myself reflected in Shakespeare's world,” she confides in the opening chapter, “maybe that meant I wasn't as unnatural as I feared.” (p. 21) Though I had difficulty relating to either subject, I found her story and writing engaging and moving. I liked it so much that I bought a hard copy. Four days later, covid19 hit home: Both Ball State and Butler canceled all remaining in-person classes, and quarantine began. Since March 12, I've barely left the house. The first several weeks were extremely stressful, as all the courses I was taking and teaching suddenly switched to online formats. After that chaos settled and I acclimated to the new normal, I knew I had to find something new to engage with intellectually. Taking and teaching classes is, of course, extremely intellectually challenging (that's why I enjoy it), but I needed something more – something I'd never done before. I'd never read Shakespeare outside of school. My freshman high school English class studied ROMEO AND JULIET (for which I composed my opus 1, a piano solo that I'm still rather proud of), my sophomore class covered MACBETH, and I scrutinized HAMLET last fall for a doctoral seminar – all three of which I struggled with, but ultimately enjoyed. And so, inspired by Keenan and those three plays, I bought a used copy of THE RIVERSIDE SHAKESPEARE on Amazon for $12 and embraced my new-found quarantine-induced free-time. It took 69 days (of course it did!) and about 400 hours (estimating an average of 5-6 hours per day) to read all 38 plays at least once (8 of them twice). As I finished each one, I awarded entirely subjective ratings out 10. Below is my ranking system and initial thoughts (a mix of summary, explanation, and criticism) on all 38. 1/10 – Few redeeming qualities (1 play) 2/10 – A few standout qualities (1 play) 3/10 – Significant problems (4 plays) 4/10 – Slightly more bad than good (3 plays) 5/10 – Equal parts good and bad (3 plays) 6/10 – Slightly more good than bad (5 plays) 7/10 – Good, but with problems (9 plays) 8/10 – Very good (5 plays) 9/10 – Excellent (4 plays) 10/10 – Extremely compelling (3 plays) 1/10 – Few redeeming qualities (1 play) TROILUS AND CRESSIDA This was the only play that tempted me to give up. I found the story and characters bland. That combined with its length (3,592 lines makes it Shakespeare's seventh-longest play) made TROILUS a slog! It was also one of the most challenging plays to understand and least rewarding – I put more effort into deciphering TROILUS than any other, yet got less out of that effort than any other. 2/10 – A few standout qualities (1 play) ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA Objectively, this isn't a terrible play; but subjectively, I couldn't stand it – I hate all the main characters! Antony is a hollow shell of a man, never able to balance what he wants with he needs, and incapable of long-term planning; Cleopatra is an ancient example of manic/depressive bipolar disorder and its problems when not properly managed; Caesar cares mostly about public image (a true politician); Lepidus is feeble and out-matched by every other character, even though he's the eldest and most experienced; Pompey craves power yet refrains when opportunity knocks, not out of moral outrage but out of concern for what people will think of him. Clearly that's all part of Shakespeare's plan – it is a tragedy, after all – but I don't find terrible decision-making engaging. 3/10 – Significant problems (4 plays) TWO NOBLE KINSMEN I quote from this play in my “Baseball Before the Civil War” presentation (it references stoolball, a predecessor to modern day baseball, in V.ii.74), so I was quite eager to read the entire play and thus have a better understanding of the larger context in which that quote appears. But I was disappointed: The characters and plot make no sense! The title characters are cousins Palamon and Arcite. Captured in battle and imprisoned together, they swear enduring allegiance and mutual affection. “[H]ere being thus together,” comments Arcite with more than a hint of homoeroticism, “We are one another's wife” (II.ii.78-80). “You have made me / (I thank you, cousin Arcite) almost wanton / With my captivity”, Palamon immediately reciprocates. “What misery / It is to live abroad” (95-8). All of that changes, however, as soon as they spot Emilia. Both are immediately smitten and start competing to win her hand, despite her lack of interest in either man. For some reason, “The cause I know not” (222), Arcite is released from prison and “Banish'd. … [N]ever more / Upon his oath and life, must he set foot / Upon this kingdom.” (244-6) But, still infatuated with Emilia, he remains, and enlists in a foot race and wrestling tournament (wha?), where he wins both (wha??), and thus wins Emilia's hand in marriage (wha???). Meanwhile, the jailer's daughter (she's never given a name) falls in love with Palamon (even though he despises her), and busts him out of prison (even though that means her father will be executed for failing to retain his prisoners) in the hope that he'll love her in return. Instead, he ignores her, and immediately pursues Emilia, unaware that she's now betrothed to Arcite. Eventually, the cousins reunite and agree to fight to the death (wha????), with the winner wedding Emilia (wha?????). As they joust, the local Duke enters. “Save their lives,” he orders in III.vi.251, “and banish 'em”, apparently forgetting that he had banished Arcite already, just one scene prior! Shortly thereafter, Palamon and Arcite resume their scuffle, and Arcite proves victorious. With Palamon about to be executed, news arrives that Arcite has been fatally wounded in horse accident (wha??????) and so Palamon can marry Emilia after all. In the midst of all that, a wooer (he is never given a name, either) pretends to be Palamon in order to trick the jailer's daughter into marrying him (wha??????????????????). Clear as mud, right? And that's why KINSMEN is so problematic – nothing makes any sense! I associate this play with TWO GENTLEMEN OF VERONA (see below), which also features two young men jockeying for the love of a single woman. But VERONA is the better play because the characters and situations actually make some sense (until the very end – but I'll address that later). KING JOHN and HENRY VI, PART ONE My favorite part about reading Shakespeare's history plays was that I knew basically nothing about English political history, so every bit of information was new and stimulated my curiosity. I watched a dozen or so documentaries as I read through those ten plays, which greatly enhanced my understanding of the historical events on which they are based. That being said, my least favorite part was the asinine decision-making of the characters – these people were all idiots! And that inanity is highlighted in KING JOHN and HENRY VI, PART ONE, both of which revolve around differing interpretations of the royal line of succession. It begs the question: Why didn't somebody determine the rules of succession beforehand?! KING JOHN is most significant in the context of Shakespeare's other histories. It has little merit on its own, rather like how the STAR WARS prequels relate to the original trilogy. Its most important lines come at its close, which issue a stern warning against English civil war: This England never did, nor never shall, Lie at the proud foot of a conqueror, But when it first did help to wound itself. ... Come the three corners of the world in arms, And we shall shock them. Nought shall make us rue, If England to itself do rest but true. (V.vii.112-8) That prophesy unfolds most clearly in HENRY VI, PART ONE. “[W]hat a scandal is it to our crown”, King Henry VI berates his underlings in III.i.69-73, “That two such noble peers as ye should jar! … Civil dissension is a viperous worm / That gnaws the bowels of the commonwealth.” As foretold in JOHN, that civil disobedience has foreign ramifications as England loses control over France. HENRY VI, PART ONE might also be Shakespeare's least poetic play – the verse (or rather lack thereof) and imagery lacks depth and nuance (excepting IV.v). It's also not a terribly long play (2,931 lines), but it feels like it is given how little actually happens in it. THE WINTER'S TALE I know this is a favorite for many Shakespeare enthusiasts, but, like ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA, I find the characters (mostly Leontes) flat and obnoxious. Leontes' unfounded jealousy destroys his family and his kingdom, then he suddenly changes his mind when “Apollo's priest” tells him he's being an idiot (III.ii.127-36). “The heavens themselves / Do strike at my injustice”, he claims out of nowhere in III.ii.146-7 & 153-5. “Apollo, pardon / My great profaneness 'gainst thine oracle! I'll reconcile me”. Redemption is one of the most difficult character arcs to execute well. A good example comes from STAR WARS: Darth Vader is redeemed at the end of RETURN OF THE JEDI. In that case, though, Vader's redemption doesn't come out of nowhere (like Leontes'), but rather is the result of carefully planted seeds in the previous films that set up this transformation. Such seeds are nowhere to be found in THE WINTER'S TALE, thus Leontes' redemption is undeserved on the part of the character and clumsy on the part of the author. 4/10 – Slightly more bad than good (3 plays) ALL'S WELL THAT ENDS WELL If Leontes in THE WINTER'S TALE is the worst example in Shakespeare of unearned redemption, then Bertram in ALL'S WELL is the second-worst offender. He's forced to marry Helena (who genuinely loves him) at the start, even though he can't stand her. The middle of the play continuously establishes him as a terrible person, and then in the last few lines he suddenly repents. This transformation is not earned – it only happens as a way to end the story happily. That leads to the second major problem: If TWO GENTLEMEN OF VERONA (see below) exhibits the most egregious example of “tie it up in a bow” syndrome, then ALL'S WELL is the second-worst offender. The drama wraps up so abruptly, that it's almost like Shakespeare said, “Iunno how to end this, so I'll just throw in a happily-ever-after conclusion, and call it ALL'S WELL THAT ENDS WELL!” TWELFTH NIGHT Everybody loves this one, but I find it convoluted and tedious. Some of Shakespeare's plays read as if they took no effort at all to write – as if a complete and perfect idea flashed through his brain in a moment of profound inspiration, and all he had to do was write it down without changing a word. TWELFTH NIGHT is the opposite of that – I imagine Shakespeare had a brilliant but preliminary idea, then struggled to find a way to make that idea make sense, contorting this and tweaking that until he ended up with product that sort of makes sense, but not really. On the other hand, the strong theme of gender-bending (even more so than in other Shakespeare plays) makes this a much more interesting work in the 21st century than it could have been in the early 17th, even though women were legally barred from performing on stage at that time. Obviously, contemporary productions have much more freedom to play with these undercurrents of homoeroticism than actors had in Shakespeare's day. THE MERCHANT OF VENICE I will forever associate THE MERCHANT OF VENICE and TWELFTH NIGHT – both are highly regarded works that I struggle to enjoy. The horrors of the Holocaust inevitably give this play (which centers on the Jewish character Shylock) a different tone than it had in Elizabethan England (when practicing Judaism was illegal). It seems to me that Shakespeare never intended his audience to sympathize with Shylock, but instead view him as a laughingstock as he endures one devastating loss and humiliation after another. A more modern and empathetic interpretation makes Shylock sympathetic. Thus, like TWELFTH NIGHT, VENICE is also a play that has much more to offer in contemporary interpretation and production than it would've had when it was written. 5/10 – Equal parts good and bad (3 plays) CORIOLANUS Rather similar to Richard Wagner's opera RIENZI, CORIOLANUS tells the story of a valiant Roman soldier who, falsely accused by Rome's citizens and thus banished from the city, teams up with Rome's enemy, the Volscians, to destroy Rome in revenge. But after a visit and pleas from his wife and young son, Coriolanus cancels the attack. That ticks off the Volscians, who plan to kill Coriolanus for abandoning them, but the fickle Roman public beat them to it, killing the title character in the final scene for some reason that either I missed or is not clearly explained. It's really not a bad play, but it's really not good, either. But it does address several topics that remain relevant: wealth and its uneven distribution throughout society, and the capricious nature of public opinion. As a side note, it also includes some of Shakespeare's best insults in II.i:

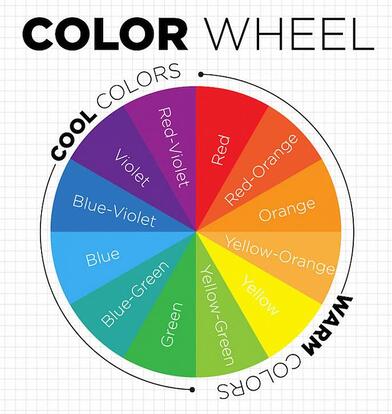

TIMON OF ATHENS Most Shakespeare plays either start better than they end, or end better than they start. TIMON is definitely the former. It begins with the title character throwing large parties, forgiving debts, and buying excessive gifts for his friends. In gist, Timon is generous to a fault, and his debts eventually ruin him. Never fear, he thinks, I have many friends who will help me out! But alas, all those who he thought were true friends abandon him, and Timon dies alone and resentful. There's so much more Shakespeare could have done with this premise – it feels like a missed opportunity! HENRY VI, PART TWO The bickering over who is the rightful king that started in HENRY VI, PART ONE (see above) continues in PART TWO. One of the major turning points in this civil war – and probably King Henry's biggest tactical error – comes when a small group of Henry's court turn him against his loyal uncle, Humphrey. “Thus King Henry throws away his crutch”, Humphrey spits ominously and presciently as he's hauled off to prison (III.i.189-90). This is similar to OTHELLO and JULIUS CAESAR in how characters are persuaded to act against another character who is close to them. After Humphrey's death, the court devolves into chaos as one character after another is murdered as the two rival factions compete for the crown. The play is left unresolved, setting up HENRY VI, PART THREE (see below). 6/10 – Slightly more good than bad (5 plays) THE MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR Legend has it that Queen Elizabeth, upon viewing HENRY IV, PART ONE, loved the character Falstaff so much that she personally requested a sequel. Shakespeare responded with THE MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR, in which Falstaff is the victim of three pranks orchestrated by the title characters. But the witty and engaging Falstaff from HENRY IV is almost unrecognizable from the bumbling idiot Falstaff from MERRY WIVES. Their characters are so different that, if not for the same name, I'm not sure I would have realized they are same person. That being said, it's enjoyable and engaging, if not terribly special. Verdi's opera, on the other hand, I found utterly uncompelling. OTHELLO Verdi wrote a much better opera based on OTHELLO, commonly regarded as one of Shakespeare's masterpieces, but I genuinely hate the title character. I have no sympathy for any husband who refuses to trust his wife. Instead, he succumbs to jealous suspicions, and murders her. The most compelling character is certainly Iago, the villain, who tempts Othello “into a jealousy so strong / That judgment cannot cure” (II.i.301-2). And I feel sorry for the other characters who suffer as a result of Othello's poor decisions – Desdemona in particular. But I certainly don't feel sympathy for Othello. If anything, I feel pity towards him: He made a string of ridiculously bad decisions, only recognizing his errors after it was too late. Dare I say Othello got what he deserved? For a more compelling story of a character coerced into murdering someone he really doesn't want to kill, see JULIUS CAESAR. HENRY VIII Written in 1613, ten years after Queen Elizabeth's death, HENRY VIII is clearly nostalgic for her reign. I don't know what Shakespeare thought of Elizabeth's successor, King James I, but based on this play I'm guessing he much preferred her over him. The Tudors (of which Queen Elizabeth was the last) are perhaps the most fascinating family of English monarchs, and Henry VIII, with his six wives, could've yielded a more interesting dramatic adaptation than this. Shakespeare instead glorifies Elizabeth – her birth being the climax of this play. It's drenched in nostalgia; unfortunately, that does not a compelling story make. THE TAMING OF THE SHREW As a child, whenever I heard of this play, I assumed it meant this kind of shrew... … and, being fascinated with all things nature, I was extremely disappointed when (not until high school, I'm embarrassed to admit) I finally figured it out the shrew was actually a tempestuous woman named Katherina. Reading it some twenty years later, I can appreciate the artistry of the script, but I have severe misgivings over its misogyny, as Katherina is literally and figuratively beaten into obedience by her husband. Many readers don't find SHREW misogynistic, but I have a hard time drawing any other conclusion. Like Shylock in THE MERCHANT OF VENICE, I suspect Shakespeare intended his audience to find Katerina's submission amusing – perhaps the Elizabethan equivalent of Adam Carolla and Jimmy Kimmel's THE MAN SHOW. MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING The original romcom, MUCH ADO is another play more highly regarded in consensus than by me personally. The play made more sense to me when I read somewhere that in Shakespeare's day, the word “nothing” was pronounced “noting”, which can refer to eavesdropping, which occurs frequently throughout MUCH ADO and leads to several humorous misinterpretations. It also opens up ADO to musical exploration – music being based on notes. Indeed, I count 21 musical references – some explicit, some subtle. Lastly, it has also been observed that the word “nothing” is Elizabethan slang for vulva. “Men have a 'thing' between their legs”, explains Jillian Keenan, “woman have 'no thing.'” (p. 128) Lastly, though I'm no fan of Hector Berlioz, his opera BEATRICE AND BENEDICK is surprisingly good! I love how Berlioz adds a musical rehearsal within the opera, much like how Shakespeare frequently (though not actually in this case) employs a “play within the play”. 7/10 – Good, but with problems (9 plays) HENRY IV, PART TWO The coming of age story of Prince Henry (aka Hal) that started in PART ONE (see below) naturally continues in PART TWO. By the end of the sequel, he has been crowned King Henry V, and rejects his unruly youthful behavior to assume his royal role. Along with his base nature, he rejects his base friends, most notably Falstaff, whom Henry brutally disowns in the final scene. That loss, however, is counterbalanced by the addition of a new character, who also serves as a father substitute: the Lord Chief Justice. Where Falstaff is a father figure for Hal, the Lord Chief Justice is a father figure to Henry V. And when base Hal transforms into noble Henry, Falstaff becomes irrelevant. PERICLES Where HENRY IV explores the father/son relationship, PERICLES explores that of the father/daughter. While several such relationships appear throughout, the main focus is on the title character and his daughter, Marina. Pericles, his wife Thaisa, and Marina are all separated shortly after Marina's birth; the play ends happily, when all three are reunited. Though an extremely quick read, there's a lot of plot to keep track of – maybe even rivaling CYMBELINE for Shakespeare's most plot-heavy work. TWO GENTLEMEN OF VERONA VERONA is one of Shakespeare's earliest plays, and his immaturity shows in the clunky characters and situations. It is guilty of the worst example of “tie it up in a bow” syndrome I've ever encountered – STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION has nothing on VERONA in that department! The title characters are friends Valentine and Proteus. Though Proteus is betrothed with Julia, he develops an interest in Valentine's girlfriend, Silvia. When Silvia rejects Proteus, he attempts to rape her. “I'll woo you like a soldier,” he threatens in V.iv.57-8. “And love you 'gainst the nature of love – force ye.” Valentine arrives just in time to stop the rape. “Who should be trusted, when one's right hand / Is perjured to the bosom?” he shames his former friend in V.iv.67-9. “I must never trust thee more”. But then, in a sudden reversal that comes out of nowhere and undermines the entire play up until this point, Valentine forgives Proteus, saying, “All that was mine in Silvia I give thee.” (83) But for some crazy reason, Proteus equally suddenly and equally out of nowhere decides that Julia is more beautiful after all (“What is in Silvia's face,” he questions in V.iv.114-5, “but I may spy / More fresh in Julia's”) and marries her, allowing Valentine to marry Silvia. And they all lived happily ever after. The end. (Wha???????????) Criticisms aside, I find this play most compelling in how the ideas at play would resurface in Shakespeare's subsequent work: cross-dressing, city vs. country, homoeroticism, characters lower in social status are higher in moral integrity, appearance vs reality, women as more logical than men, and forgiveness all feature prominently in VERONA and in his later plays. So by itself, TWO GENTLEMAN OF VERONA might not be compelling, but in the context of Shakespeare's entire career as a playwright, there's a lot to engage with. In that sense, we might think of VERONA as a counter-balance to CYMBELINE. CYMBELINE Where VERONA (written 1594) is a hodgepodge of aspects that would surface again in Shakespeare's subsequent plays, CYMBELINE (written 1609-10) does likewise but, coming at the end of his career, can be seen as a summation of his previous works. For that reason, I associate the two – neither are bad plays, but their ultimate contribution to Shakespeare's oeuvre is how they combine aspects of his other, more significant, accomplishments. THE TEMPEST Strong humanist and enlightenment values (ie: forgiveness) help make this one of Shakespeare's most mature works. I can't quite put my finger on it, but I sense strong similarities between Shakespeare's THE TEMPEST and Richard Wagner's last opera PARSIFAL. Prospero's words in I.ii.89-90 resonate with my own current quarantine situation: “I, thus neglecting worldly ends, all dedicated / To closeness and the bettering of my mind.” This passage also reminds me of LOVE'S LABOUR'S LOST (see below), in how the mind inevitably succumbs to the heart. “The strongest oaths”, observes Prospero in IV.i.52-3 “are straw To th' fire I' th' blood.” Those words would fit nicely in LLL IV.iii. KING LEAR Many readers consider LEAR Shakespeare's finest play, but I found it overly long and complicated. The highlight of this convoluted play is III.iv, in which Lear (who is genuinely going mad) meets and bonds with Edgar (who is pretending to be mad to protect himself from unwanted attention). Despite Lear's advanced age, this scene develops his nascent empathy as Edgard's antics resonate with Lear's equally nascent insanity, resulting in a most strange and wonderful understanding – even intimacy – between the two men. This set up has lots of potential, but it never earns the emotional payoff it seeks. RICHARD III Richard III's Machiavellian rise to power and prompt fall is ultimately about conscience, of which the title character has none until the final act, when all the ghosts of those he murdered (representing his conscience) return to haunt him. There are many parallels between Richard III and Donald Trump that make this 427-year-old play still applicable in 2020. Just last week, National Guard troops fired tear gas into a crowd of protesters near St. John's Episcopal Church in Washington D.C. to clear the way for a Trump photo op in which he was rumored to hold the Bible upside down. A similar scenario plays in III.vii of RICHARD III: He organizes a publicity stunt in which a crowd sees him as he appears to be praying. “[L]ook you get a prayer-book in your hand,” advises Richard's right-hand man, “And stand between two churchmen … Two props of virtue of a Christian prince, / To stay him from the fall of vanity; / And see a book of prayer in his hand” (III.vii.47-8 & 96-8). Despite its current relevance, the play suffers from a lack of subtlety (it's like Shakespeare doesn't trust his audience to make connections, and so spells everything out) and an excess of length (at 3,887 lines, only HAMLET is longer). TITUS ANDRONICUS TITUS clicked for me when I started imagining it as a Richard Strauss opera. It would make a better modernist companion to SALOME than ELEKTRA. How come Strauss never wrote it? HENRY VI, PART THREE Easily the best of the Henry VI trilogy, PART THREE delves into the mind of King Henry VI as he struggles to control the civil disputes that constituted the War of the Roses. And it's the psychological state of the king – not the physical war of his subjects – that makes PART THREE compelling. It opens with Henry brokering a compromise with his rival, Richard Plantagenet (not to be confused with Richard II, who is entirely unrelated, or Richard III, who is his son): They agree to let Henry's reign continue until his death, whereupon Richard (or his descendants) will assume power. While this truce puts a temporary end to the bloodshed, it pisses off both Henry's and Richard's subjects. Henry's queen, Margaret, is furious that Henry disinherited their son, Edward. “[T]hou prefer'st thy life before thine honor” she fumes in I.i.244-6. “Soldiers should have toss'd me on their pikes, / Before I would have granted to that act”. What's so fascinating is why Henry made this decision: Disinheriting Edward is his way of saving his son from experiencing the problems he himself has faced as king. “I'll leave my son my virtuous deeds behind,” Henry waxes in II.ii.49-50, “And would my father had left me no more!” Henry VI's reign has been so plagued with problems and infighting that he wishes he had never inherited the throne in the first place. By ensuring his son will not inherit the throne, Henry assures that his son will lead a better, if less historically important, life. 8/10 – Very good (5 plays) JULIUS CAESAR How similar OTHELLO and JULIUS CASEAR are! Both center on characters coerced into murdering someone who they really don't want to kill: Iago brainwashes Othello into uxoricide by spreading rumors of her infidelity; Cassius seduces Brutus into assassinating Caesar for being a tyrannical dictator. The problem: Neither claim is true – Desdemona is faithful to Othello; Caesar never displays the dictatorial ambition that doomed him (at least not in the play – maybe he did in real life). But here's the difference: All Othello had to do was trust his wife. Brutus' situation is far more subtle and complex because you can't just go up a dictator and ask him if he's a dictator! Cassius convinces Brutus that the people of Rome worry that Caesar will turn into a dictator, and thus want him dead. Brutus' job, as a public representative, is to act on behalf of the people he represents, even though he's friends with Caesar. So in Brutus' mind, he has to make a decision: Do my job and kill my friend, or save my friend and neglect my responsibilities? It's a far more compelling choice than Othello's. The other big difference is in structure and scope: Othello kills Desdemona in V.ii; Brutus kills Caesar in III.i. Where OTHELLO is the story of a lover deceived into believing his wife unfaithful, CAESAR is more about the aftermath of a fateful murder (similar to MACBETH). That said, I found the first three acts much more compelling than the last two. THE COMEDY OF ERRORS This one is not commonly regarded as among Shakespeare's best, but I quite enjoyed it – it's exactly what it's trying to be: a comedic romp. No more, no less. Like SOLO, ERRORS sets an admittedly low target, and hits that target dead center. It is exactly what it tries to be. It's not terribly sophisticated because it doesn't need to be. The exposition is slow (especially act one), but once the premise is set up, the writing is effortless and funny. MEASURE FOR MEASURE Highly relevant in the #MeToo era, MEASURE FOR MEASURE depicts Angelo, a high-ranking government official, who threatens to kill Isabella's brother unless she sleeps with him. “You must lay down the treasures of your body”, he intones in II.iv.96-97, “or else to let him suffer”. When Isabella threatens to expose his extortion, he resorts to sheer intimidation. “Who will believe thee, Isabel?”, he purrs mirthlessly. “My unsoil'd name, th' austereness of my life, / My vouch against you, and my place I' th' state, / Will so your accusation overweigh[.] … [M]y false o'erweighs your true.” (154-7 & 170) It's a study of how authority corrupts, or, as Shakespeare himself wrote, “If power change purpose” (I.iii.54). The play's problem is its ending. While the first several acts are gripping and intense, it concludes with several marriages (including Angelo's, though not to Isabella) and everybody lives happily ever after. Simply put, the ending doesn't match the start. That beginning is so powerful that the play as a whole is still very compelling, but it prevents me from ranking higher than 8/10. A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM This one clicked for me when I realized the city of Athens represents the intellectual side of humanity, while the forest represents the emotional side. Lysander and Hermia's flee “to that place the sharp Athenian law / Cannot pursue us” (I.i.162-3) can thus be seen as a flee from the overly-controlled city life to a more lax rural existence. And from there, it's easy to interpret the play as emphasizing the emotional side of human nature over the rational. The rest of the play, with its magical fairies and love potions, fits solidly in the realm of fantasy, including Puck's concluding soliloquy: You have but slumber'd here While these visions did appear. And this weak and idle theme, No more yielding but a dream (V.i.425-9) Thus, the play as a whole seems to support the emotional/fantastical/whimsical side of human nature over the rational/practical/routine. As an intellectual in Trump's America, I have major problems when this “emotion over reason” principle is overdone. But it's also a reminder (like LOVE'S LABOUR'S LOST) that too much emphasis on the rational can also have severe consequences. And that's my ultimate takeaway from MIDSUMMER: the need for balance between the intellectual and emotional sides of human nature. HENRY IV, PART ONE Though King Henry IV is the title character, this is more the story of his son, Prince Henry (nicknamed Hal). Where PERICLES centers on the father/daughter dynamic, both parts of HENRY IV center on the father/son dynamic. Hal is a rambunctious and irresponsible playboy at the start of PART ONE, stoking his father's jealousy. “Thou mak'st ... me sin / In envy”, laments the king in I.i.78-88, “that my Lord Northumberland / Should be the father to so blest a son[.] ... O that it could be prov'd / That some night-tripping fairy had exchang'd / In cradle-clothes our children”. Fed up with his biological father and the royal responsibilities that accompany him, Hal finds a makeshift father figure in Falstaff, a portly and witty knight who encourages Hal's boisterous behavior. The famial tension comes to a head in III.ii, as biological father and son meet on stage for the first time. “[T]hou hast lost thy princely privilege / With vile participation”, the elder Henry reprimands the younger. “Thy place in Council thou hast rudely lost, / Which by thy younger brother is supplied” (86-7 & 32-3). Thereupon Hal oaths atonement through the killing of Lord Northumerland's son, Percy, who is helping lead a rebellion against King Henry. “I will redeem all this on Percy's head,” the younger swears, “[T]he time will come / That I shall make his northren youth exchange / His glorious deeds for my indignities.” (132 & 144-6) Indeed, Hal kills Percy in V.iv, marking his first major rite of passage toward what will ultimately be his own reign as King Henry V. 9/10 – Excellent (4 plays) ROMEO AND JULIET This was the first Shakespeare play I ever read, back in high school. It was also the first I read for my “Complete Shakespeare Quarantine Challenge”, back on April 2. It clicked for me when I discovered a connection with STAR WARS. Attack of the Clones features the musical theme Across the Stars, the title of which references the “star-crossed lovers” of R&J's famous prologue (6). Plus, the notion of forbidden love so prominent in R&J is also present between Anakin Skywalker and Padme Amidala. Furthermore, R&J features extensive space imagery (sun, moon, stars most obviously, but also clouds, night, light and darkness, eyes, dreaming, fire), all of which further the parallels with science fiction. Lastly, R&J might be Shakespeare's most poetic play – or at least the most poetic of the tragedies. In no other is his use of text painting (how the words and verses Shakespeare implemented relate to and help convey their semantic meanings) more effective than in I.v, where Romeo and Juliet meet for the first time and suddenly speak synchronously in flawless Shakespearean sonnet structure. LOVE'S LABOUR'S LOST King Ferdinand of Navarre seeks fame and fortune by starting a school. (Wha???) To ensure strict and proper focus solely on academic pursuits, all teachers must renounce sex for three years. “The mind shall banquet,” trumpets one instructor in the opening scene, “though the body pine” (I.i.25). Yeah, no – that doesn't last long! Even before the first scene concludes, another character predicts problems: “Such is the simplicity of man to hearken after the flesh.” (217-8) By the second act, “Navarre is infected … With that which we lovers entitle 'affected.'” (II.i. 230-2); and by the fourth act, they all agree to abandon the no sex rule, “For none offend where all alike do dote.” (IV.iii.124) But the joke is on them, for the women who inspired this mass exodus from promise refuse their amorous advances in the fifth act! It's not all bawdy jokes, however. The underlying message is a warning against overly academic pursuits. In other words, don't let the heart suffer for the head. The schoolmaster Holofernes is an obvious and amusing symbol of the pointlessness of pedantic academic discourse for its own sake – a warning that many academics have failed to heed! It's also one of Shakespeare's most poetic plays – what ROMEO AND JULIET is to the tragedies, LOVE'S LABOUR'S LOST is to the comedies. The problem with poetic language, of course, is intelligibility. Certain passages required re-re-re-reading to figure out what was being said. LLL also has structural problems, and at times is unnecessarily long (like when the guys dress up as Russians in V.ii for some hair-brained reason). It's as if Shakespeare sketched out the entire play, then decided it wasn't long enough, and so padded. HENRY V Where its two predecessors focus on young Hal's coming of age, HENRY V shows the title character in full maturity as he valiantly leads his country to victory in the Battle of Agincourt. The play shines brightest when Henry is alone on stage, soliloquizing on his anxieties as leader. It is in those scenes that he, temporarily unconcerned about maintaining his royal image, appears most vulnerable, most human, most intimate, and most compelling. “What have kings, that privates have not too, / Save ceremony?” he ponders in IV.i.238-40. “And what art thou, thou idol ceremony? … But for ceremony, such a wretch, / Winding up days with toil, and nights with sleep, / Had the forehand and vantage of a king.” In other words, the biggest difference between himself and his subjects is mere pomp and circumstance – ultimately meaningless. Henry's conclusion (that he's not inherently better than any of his subjects) culminates in his famous St. Crispin's Day speech and the best-known lines of the play: “We few, we happy few, we band of bothers; / For he to-day that sheds his blood with me / Shall be my brother” (IV.iii.60-2). And that's my main takeaway from this play: That all people are created equal. Shakespeare said it 177 years before Thomas Jefferson. HAMLET Though I mildly disagree, the consensus regards HAMLET as Shakespeare's best work (some have even claimed it's the greatest literary accomplishment ever in English). Rather like Henry V, Hamlet's psychological anxieties are highlighted – the whole play revolves around him trying to figure out how to revenge his father, but of course there is no right way to commit murder! He's entrenched in a true dilemma: damned if he does, damned if he doesn't. It seems that those who find Hamlet's existential quandary compelling rate this play extremely highly, while those (like myself) who find him a touch whiny and annoying rate it slightly lower. 10/10 – Extremely compelling (3 plays): How curious that I ranked onetragedy, one history, and one comedy 10/10. MACBETH If MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING is the original romcom, then MACBETH is the original horror. (The 2010 film starring Patrick Stewart did a fantastic job of taking the horror this play must have for audiences four hundred years ago and translating it for a modern audience.) Shortly after murdering Duncan, Macbeth delivers one of my all-time favorite Shakespeare quotes: “Will all great Neptune's ocean wash this blood / Clean from my hand? No; this my hand will rather / The multitudinous seas incarnadine, / Making the green one red.” (II.ii.57-60) It took me a while to figure it out why Shakespeare used the color green here. Rather, I've always thought of the ocean as more blue. Then I realized that green and red are complementary colors – opposites on the color wheel. So choosing green over blue in this context emphasizes the severity of Macbeth's crime. RICHARD II On the surface, RICHARD II chronicles the 1399 deposition of the title character. Yet it is more a vehicle for Shakespeare's ruminations on the nebulous nature of grief than the story of a monarch overthrown – the plot is merely the means through which its deeper meaning is manifest. “Grief boundeth where it falls,” observes the Duchess of Gloucester in I.ii.58 & 61, “For sorrow ends not when it seemeth done.” She illustrates how challenging it can be to acknowledge, pinpoint, and address depression, and the difficulty in recognizing when the grief cycle has completed. Before I had ever read this play, I quoted II.ii.14 as the epigraph to my book FROM THE SHADOW OF JFK: “Each substance of a grief hath twenty shadows”. I found that quote while perusing the internet, and it fit the book perfectly. I didn't realize at the time that the whole play (not just that one line) was centered around those words. As Richard looses authority, his guilt and regret over his political mishandlings equally grow. Inversely reflecting this demise, Shakespeare writes progressively more poetic and insightful verse for him. Richard's sorrows – and thus his poetics – culminate in IV.i.295-302, when he is overthrown, and proclaims the most important passage of the play: My grief lies all within; And these external manners of laments Are merely shadows to the unseen grief That swells with silence in the tortur'd soul. There lies the substance; and I thank thee, king, For thy great bounty, that not only giv'st Me cause to wail, but teachest me the way How to lament the cause. AS YOU LIKE IT Love is often problematic in Shakespeare. And love at first sight all the more so. (How deep can Romeo and Juliet's love really be, when they only spoke to each other four times?) But in AS YOU LIKE IT, Shakespeare finds an ingenious way around the problem of love at first sight: Having Rosalind, disguised as a man, train Orlando how to be a good lover allows their mutual attraction to develop into a more realistic relationship. Thus, when Rosalind reveals her true identity, their professions of love are actually based on their own substantial shared experiences. Nowhere else does Shakespeare offer such a compelling celebration of the diverse and often messy romantic preferences of human beings. So, quarantine challenge complete, now what? I've been considering starting a Shakespeare blog. I already have several other blogs (The Beatles, pop music, Star Wars, and origami). My standard reasoning behind whether or not I start a new blog is if I have anything original to say. If yes, a blog is a perfect way to develop my ideas; if not, a blog seems like more work than it's worth. In this case, I have nothing original to say, yet with this post it is launched.

“If you don't know where you are going,” quipped New York Yankees catcher Yogi Berra in a witticism worthy of Shakespeare, “you might end up some place else.” Wherever my current Shakespeare obsession takes me, this blog will be a road that helps me get there. |

Shakespeare BlogA workshop for developing thoughts on William Shakespeare's writings. ArchivesCategories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed