|

I've made no attempt to hide my admiration for Richard II. One reason I find it so compelling is for how its musical imagery helps tell the story. In his essay Music of the Elizabethan Stage, John Stevens notes “an increasing subtlety in the use of music to ... reinforce the weakness, the inner collapse of Richard” (p. 17). At the start of the play, Richard, as king, wields authority – both political and musical. “The trumpets sound” for “his Majesty's approach” in 1.3. And just as Bullingbrook and Mowbray are about to battle, “A charge sound[s]” as “the King hath thrown his warder down” (line 18). “Let the trumpets sound”, Richard orders, “While we return these dukes what we decree”, followed by “A long flourish” (121-2). When he returns, he speaks of “boist'rous untun'd drums, / With harsh-resounding trumpets' dreadful bray” before banishing both combatants (134-5). The musical symbolism of Richard's jurisdiction is furthered by Mowbray, who protests, now my tongue's use is to me no more Than an unstringed viol or a harp, Or like a cunning instrument cas'd up, Or being open, put into his hands That knows no touch to tune the harmony (161-5). In each of these instances, Richard imposes his will – and his music – on others. But by the end of the play, when Richard has lost all power, this musical symbolism is reversed. Shortly before his murder in 5.5, Richard laments, “Music do I hear? / Ha, ha, keep time! How sour sweet music is / When time is broke, and no proportion kept” (41-3). One of music's fundamental components, rhythm refers to the duration of sounds and the proportional relationships between them. When those proportions aren't properly maintained, rhythmic chaos reigns. The most interesting part about this scene, however, is questioning if this “sour music” is real: Is Richard actually hearing poorly performed music, or is the music perfectly played and thus its distortion is only in his mind? (This has obvious parallels to the ghost in Hamlet.) If the former, then Richard's (and Hamlet's) grasp on reality is still strong; if the latter, it implies Richard's (and Hamlet's) descent into insanity. The handling of this scene and is one of the important musical choices a director must make. Three of the six productions I've found have employed music that does keep time properly. I have not been able to find a single production in which the “sour music” is actually sour (meaning clearly rhythmically problematic), though two of the six (described momentarily) are rhythmically ambiguous. In the YouTube video below (Brussels Shakespeare Society, 2012, directed by Charles Bouchard, composer unknown), solo guitar music is heard at 2:13:22, and is well-performed (clearly with correct and well-proportioned rhythm). In this second YouTube video (a 1960 audio drama, neither director not composer specified), the music starts about 2:24:31, and is also well-performed. In The Hollow Crown (2012, directed by Rupert Goold, with music by Dan Jones), the music commences at 2:16:10, and is likewise well-performed. Curiously, Deborah Warner's 2016 direction, starring Fiona Shaw as the title character, does not include any music during this scene (seen at 2:03:44), perhaps implying that everything is in Richard's mind. Lastly, two productions employ a solo monophonic instrument: The Royal Shakespeare Company's 2014 production uses a recorder at 2:26:06; and the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre's audio recording a bassoon at 2:40:38. In both, the rhythms and meters are ambiguous – only the performer knows for sure how s/he is counting it mentally, but no obvious metric pattern is discernible to the audience. Richard's perception (real or imagined) of this disproportioned music inspires his ruminations on a connection between music and life: So is it in the music of men's lives. And here have I the daintiness of ear To check time broke in a disordered string; But for the concord of my state and time Had not an ear to hear my true time broke. I wasted time, and now doth time waste me (44-49). Richard sees the music as symbolic of his political mishandlings, which led to his deposition and current imprisonment. But, in true tragic form, it's too late – Richard, like the Marley brothers in Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol, recognizes his mistakes only when their rectification is beyond his grasp. Just as Richard destroyed a mirror that accurately allowed him to see himself in 4.1, he likewise calls for the music, which also provides genuine insight into his problematic self, to cease. This music mads me, let it sound no more, For though it have holp mad men to their wits, In me it seems it will make wise men mad (61-3). But music, being immaterial, cannot be as easily shattered as a tangible mirror. Moreover, even if music could be shattered, Richard no longer posses the authority to command it. “Whereas as king he had power over his trumpets, and made them express his royal will,” continues Stevens, “now another man's wish imposes this unroyal music on him and puts him into its power” (p. 18). Though Shakespeare specifies exactly where “The music plays” (line 41), he does not specify where the music stops. It seems unlikely that the music, which began with no input from Richard, would conclude upon his command, yet the script offers no explicit commentary to either support or deny that notion. The turning point for Richard's musical command – and the turning point for his power in general – comes when his uncle, John Gaunt, dies in 2.1. Prior to Richard's entrance, Gaunt comments how the tongues of dying men Enforce attention like deep harmony. … More are men's ends mark'd than their lives before. The setting sun, and music at the close As the last taste of sweets, is sweetest last (5-6 & 11-3). In other words, that which occurs at the end of something often receives more attention than that which occurs at its beginning. In this context, Gaunt means that his criticisms at the end of his life should receive more weight than any previously mentioned. But this “sweetest last” idea applies to music, too. Though not yet true in Shakespeare's day (he died in 1616), this is an accurate summary of common practice functional harmony (ca. 1650-1900). Indeed, the entire discipline of Schenkerian analysis is predicated on an elaborate prolongation of tonic that ultimately leads to a predominant-dominant-tonic cadence. The ending is where the harmonic action is – that which comes before the cadence is often of significantly less harmonic interest. After Richard's entrance, Gaunt savagely berates the king. “Thy death-bed is no lesser than thy land, / Wherein thou liest in reputation sick,” he cautions. “A thousand flatterers sit within thy crown … Which art possess'd now to depose thyself.” (95-6, 100, 108) “This scene might prove a new beginning or Richard,” writes Ted Tregear in his 2019 essay Music at the Close, “however dissolute his career so far” (p. 697). But the self-centered Richard, offended that anybody would dare criticize him, instead rejects Gaunt as “A lunatic lean-witten fool / Presuming on an ague's privilege” and proceeds to intercept Gaunt's inheritance (115-6). Failing to heed Gaunt's warning proves to be the point of no return for Richard. From then on, he suffers one breakdown after another, until he winds up imprisoned and murdered in the final act. Richard II is the story of a king's gradual loss of jurisdiction. And along the way, musical imagery is constantly present to help tell it. And here's all the boring (but important) statistical stuff. Music in Shakespeare's plays assumes three distinct roles: (1) stage directions, (2) lyrics, and (3) dialog. I've found 26 explicit musical references in the script of Richard II. Of those, exactly half are stage directions.

None of the 26 are lyrics. That leaves 13 musical references in the dialog (many of which were considered above).

Lastly, what composers throughout history have written music for Richard II, as a music drama, as incidental music to accompany a performance, or as concert works inspired by it?

There is a somewhat surprising dearth of music for Richard II. I have not been able to find any operas or musicals (or even references to them) whatsoever, though that doesn't mean none exist. Perhaps the most historically important composer to write music for RII was Englishman Henry Purcell (1659-95), who, according to Charles Cudworth in his essay Song and Part-Song Setting of Shakespeare's Lyrics, 1660-1960, composed “Retired from any mortal's sight” for Nahum Tate's 1681 Bowdlerized adaptation of Richard II re-titled The Sicilian Usurper, even though it contains “not a line by Shakespeare” (p. 56). I also stumbled upon a 2019 article from The Guardian describing the premiere recording of Ralph Vaughan-Williams' score for a radio production of RII, though I've not been able to actually hear it. The only other composer of note I've been able to connect with RII (ever so tangentially) is Aaron Copland, who collaborated with Orson Welles in 1939 on The Five Kings, an adaptation of several of Shakespeare's history plays. According to aaroncopland.com, however, the manuscript remains unpublished.

0 Comments

In his book Shakespeare: His Music and Song, A.H. Moncur-Sime writes of the Comedy of Errors, "This seems to be one of the very few plays in which music bears not the slightest part." (p. 99) And John H. Long, in his book Shakespeare's Use of Music, hypothesizes that the lack of music might have been "because there was no dramatic purpose to be served by music. He could have inserted an extraneous song or two, as was often done in the plays of the period, but he did not choose to do so." (p. 52) But while there are no specific songs in the script, there are four explicit musical references - and they do serve dramatic purposes. The first comes 2.2. Unbeknownst to him, Antipholus of Syrause (hereon abbreviated AofS) has been mistaken for his identical twin brother, Antipholus of Ephesus (AofE) by Adriana, AofE's wife. “The time was once, when thou unurg'd wouldst vow / That never words were music to thine ear … Unless I spake,” she admonishes who she thinks is her husband. “[H]ow comes it, / That thou art then estranged from thyself?” (113-14 & 119-20) The musical reference in this case emphasizes AofE's affection for his wife, and thus contributes to her sense of betrayal that her “husband” no longer seems to recognize her. The second occurrence is in 3.2. Not understanding the situation, AofS plays along (pretends to be Adriana's husband) until he spies Adriana's sister, Luciana, whereupon he falls in love with her. Once AofS and Luciana are alone together for the first time, he admits his romantic interest. “Your weeping sister is no wife of mine,” he says honestly, though Luciana doesn't believe him. “Nor to her bed no homage do I owe: / Far more, far more, to you do I decline.” (42-4) How curious that he says “decline” when “incline” is the more obvious word choice – he is inclined (motivated) to love Luciana over Adriana, not declined (politely refusing). But of course this is no error on Shakespeare's part: Decline in this instance might also mean “lay down” (ie: in a bed together). And if we instead define decline as “go down”, there might even be a whiff of cunnilingus in this linguistic choice. Anyway, Luciana, still thinking that AofS is AofE and thus her brother-in-law, is horrified by the suggestion that she would so betray her sister. But AofS persists. “[T]rain me not, sweet mermaid with thy note, / To drown me in thy sister's flood of tears”, he urges. “Sing, siren, for thyself, and I will dote” (45-7). Alluding to mermaid and siren singing symbolizes the extent of his ardor and stiffens his seduction. The third instance comes at the end of the same scene. AofS rendezvouses with his servant, Dromio of Syracusa (DofS), who is stuck in a similar situation: Though he's also unaware of the error, DofS has been mistaken for his identical brother, Dromio of Ephesus (DofE), by Nell, DofE's fiance. In comparing their situations, DofE and AofE both agree that the city is cursed, and so promptly plan their departure. But in doing so, he must abandon Luciana. Oh well, he thinks, “I'll stop mine ears against the mermaid's song.” (164) Where earlier in the scene AofS referred to Luciana as both a mermaid and a siren, now he only refers to her as a mermaid. This is because sirens' song is supposedly so beautiful that anybody who heard it couldn't resist it – that's why Odysseus famously incapacitated himself before approaching the sirens in The Odyssey. AofS's resolve to leave has overruled his lust, obviously Luciana does not have the sirens' power of persuasion. Fourth and finally, in act 4.3, DofS refers to a problematic law enforcement officer as “like a base-viol in a case of leather” (23). The viol is a Renaissance- and Baroque-era ancestor to the modern violin. The bass-viol is akin to the modern cello. But Shakespeare writes base – not bass. Like the decline vs. incline pun described above, this “typo” is not an accident – it contributes to our understanding of the scene. In this context, base means inferior quality, while leather symbolizes superior quality. So describing a public safety official as such illustrates how his shady behavior has been shielded through a veneer of legitimate authority. Apparently all cops were bastards even 400 years ago! There might or might not be additional, less obvious, musical references. Russ W. Duffin observes one potential connection in Shakespeare's Songbook, pointing out that four Shakespeare plays – including Errors – might allude to the Elizabethan song 'Loath to Depart' (p. 256).

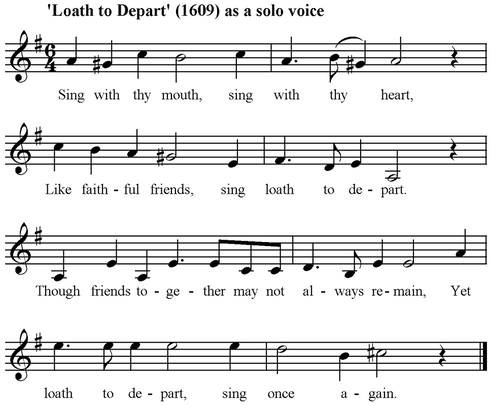

Interestingly, Duffan also notes that 'Loath to Depart' is a four-part round, which in theory could continue ad infinitum, musically capturing the hesitancy to exit articulated by the title (p. 257).

In the opening scene of Errors, Egeon utters a phrase nearly identical to that song's title while describing his unfruitful search for his missing sons: Five summer have I spent in farthest Greece, Roaming clean through the bounds of Asia, And coasting homeward, came to Ephesus; Hopeless to find, yet loath to leave unsought Or that, or any place that harbors men. (132-6) It's hardly conclusive, but certainly a possibility that Shakespeare intended this connection. And even if he never intended it, the parallel is still present Though none of them have secured a spot in the standard repertoire, history contains several operas and musicals based on The Comedy of Errors. Among the better-known adaptations are Stephen Storace's 1786 opera buffa Gli Equivoci, Henry Bishop's 1819 opera The Comedy of Errors, and Richard Rodgers' and Lorenz Hart's 1938 musical The Boys From Syracuse. It appears that the main reason Storace's opera is still remembered today has less to do with its own merits than the fact that he was a pupil of Mozart, and the libretto was written by Lorenzo Da Ponte, who collaborated with Mozart on Don Giovanni, The Marriage of Figaro, and Cosi Fan Tutte – all of which have entered the standard rep. Bishop's opera is peculiar because its overture and 14 musical numbers draw from Shakespeare's writings (and one Marlowe poem – apparently Bishop falsely attributed it to Shakespeare), but has no apparent connection to The Comedy of Errors except for its title and character names (but not character actions):

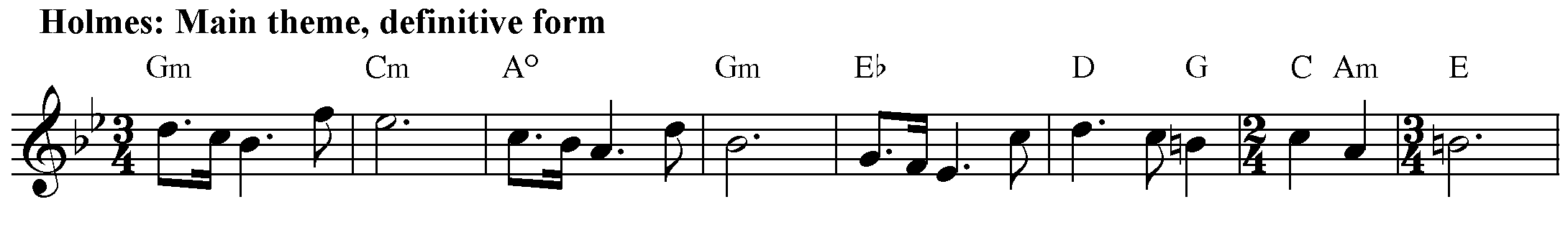

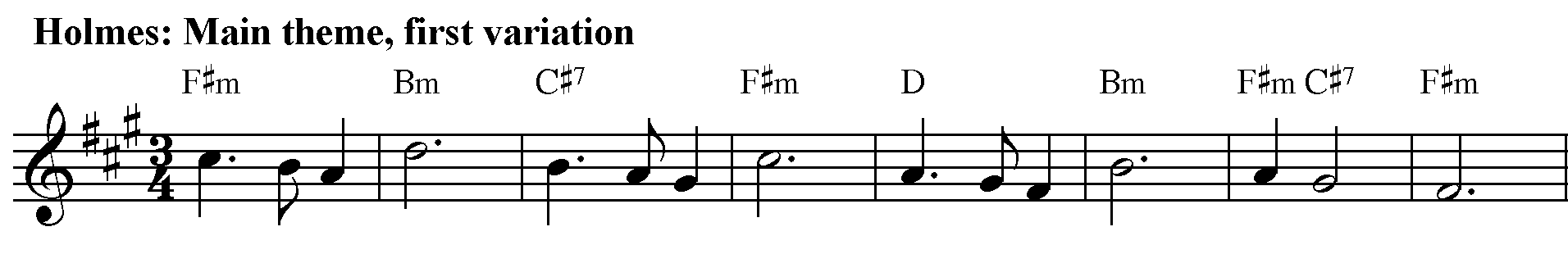

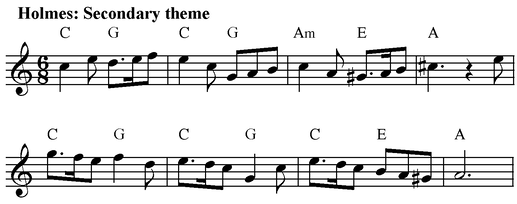

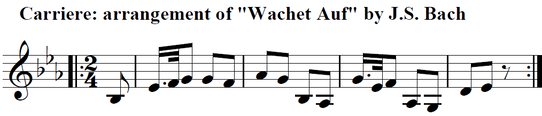

Third, Rodgers and Hart's The Boys From Syracuse is clearly based on The Comedy of Errors. Though it takes some significant departures from Shakespeare, it also adds some interesting symbolism absent from the original. As Irene Dash writes in Shakespeare and the American Musical, Hart's lyrics to 'Falling in Love with Love' features “love's blindness intrud[ing] on the romantic notion. … [L]ove makes us unable to see a lover clearly; we must struggle for hints of his reality” (p. 29): I fell in love with love one night When the moon was full I was unwise with eyes Unable to see I fell in love with love With love everlasting But love fell out with me Though Shakespeare explores the “love is blind” notion elsewhere (The Merchant of Venice: 2.6.36, A Midsummer Night's Dream: 1.1.234 & 5.1.4-22, Romeo and Juliet: 2.3.67-8, and Sonnet 148) he somewhat surprisingly does not pursue that idea in Errors, where it could nicely supplement the themes of romantic attachment and mistaken identity. Lastly, how have composers written music to accompany performances of The Comedy of Errors? Obviously, with covid19 quarantine in place, I can't attend any live performances. But, I discovered and watched two video recordings: The first was the BBC's 1983 production, directed by James Cellan Jones, with music by Richard Holmes; the other a 1989 performance by The Stratford Festival of Canada, directed by Richard Monette, with music by Berthold Carriere. Holmes' score employs two recurring themes. His main theme is heard only three times in its definitive form (at the very beginning, during the scene change from 4.4-5.1, and at the very end). However it resurfaces in disguise frequently. The first variation – clearly related in rhythm and harmony, though it has a completely different cadence – is heard between 1.2-2.1, and as intermission segues to 4.1. A second variation is heard as 3.1 transitions to 3.2. There's also a Rennaissnace-esque secondary theme that shares similarities in its cadences to the definitive version of the main theme. It is heard three times: From 2.1-2, as 3.2 segues to intermission, and from 4.3-4. Less creative, elaborate, and involved – but no less effective – than Holmes, Carriere's score is based on arrangements of J.S. Bach. While several of Bach's most famous melodies are heard throughout, a swung up-tempo rendition of the tune from his Cantata 140 “Wachet Auf” serves as the play's principal theme. Were I to compose music for Errors, I'd write a memorable main theme in two distinct tonalities – perhaps E major after Ephesus and E-flat major after Syracuse (S being German for E-flat) – to capture the whimsical nature of the story and its theme of mistaken identity. But I wouldn't try to do to much – the music would be limited to scene changes, and there'd be little underscoring. The danger of doing anything more sophisticated is that the play is already confusing enough – there's no reason to complicate further! I'd write snippets based on that main theme for each of the following:

|

Shakespeare BlogA workshop for developing thoughts on William Shakespeare's writings. ArchivesCategories

All

|

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed