|

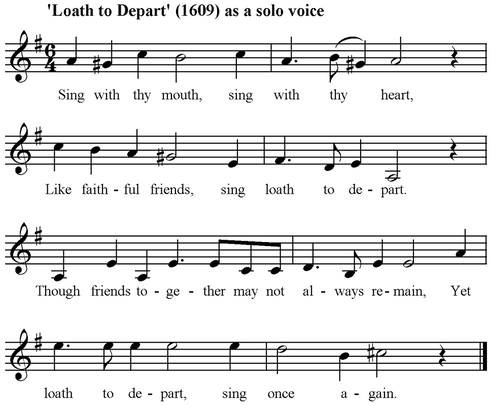

In his book Shakespeare: His Music and Song, A.H. Moncur-Sime writes of the Comedy of Errors, "This seems to be one of the very few plays in which music bears not the slightest part." (p. 99) And John H. Long, in his book Shakespeare's Use of Music, hypothesizes that the lack of music might have been "because there was no dramatic purpose to be served by music. He could have inserted an extraneous song or two, as was often done in the plays of the period, but he did not choose to do so." (p. 52) But while there are no specific songs in the script, there are four explicit musical references - and they do serve dramatic purposes. The first comes 2.2. Unbeknownst to him, Antipholus of Syrause (hereon abbreviated AofS) has been mistaken for his identical twin brother, Antipholus of Ephesus (AofE) by Adriana, AofE's wife. “The time was once, when thou unurg'd wouldst vow / That never words were music to thine ear … Unless I spake,” she admonishes who she thinks is her husband. “[H]ow comes it, / That thou art then estranged from thyself?” (113-14 & 119-20) The musical reference in this case emphasizes AofE's affection for his wife, and thus contributes to her sense of betrayal that her “husband” no longer seems to recognize her. The second occurrence is in 3.2. Not understanding the situation, AofS plays along (pretends to be Adriana's husband) until he spies Adriana's sister, Luciana, whereupon he falls in love with her. Once AofS and Luciana are alone together for the first time, he admits his romantic interest. “Your weeping sister is no wife of mine,” he says honestly, though Luciana doesn't believe him. “Nor to her bed no homage do I owe: / Far more, far more, to you do I decline.” (42-4) How curious that he says “decline” when “incline” is the more obvious word choice – he is inclined (motivated) to love Luciana over Adriana, not declined (politely refusing). But of course this is no error on Shakespeare's part: Decline in this instance might also mean “lay down” (ie: in a bed together). And if we instead define decline as “go down”, there might even be a whiff of cunnilingus in this linguistic choice. Anyway, Luciana, still thinking that AofS is AofE and thus her brother-in-law, is horrified by the suggestion that she would so betray her sister. But AofS persists. “[T]rain me not, sweet mermaid with thy note, / To drown me in thy sister's flood of tears”, he urges. “Sing, siren, for thyself, and I will dote” (45-7). Alluding to mermaid and siren singing symbolizes the extent of his ardor and stiffens his seduction. The third instance comes at the end of the same scene. AofS rendezvouses with his servant, Dromio of Syracusa (DofS), who is stuck in a similar situation: Though he's also unaware of the error, DofS has been mistaken for his identical brother, Dromio of Ephesus (DofE), by Nell, DofE's fiance. In comparing their situations, DofE and AofE both agree that the city is cursed, and so promptly plan their departure. But in doing so, he must abandon Luciana. Oh well, he thinks, “I'll stop mine ears against the mermaid's song.” (164) Where earlier in the scene AofS referred to Luciana as both a mermaid and a siren, now he only refers to her as a mermaid. This is because sirens' song is supposedly so beautiful that anybody who heard it couldn't resist it – that's why Odysseus famously incapacitated himself before approaching the sirens in The Odyssey. AofS's resolve to leave has overruled his lust, obviously Luciana does not have the sirens' power of persuasion. Fourth and finally, in act 4.3, DofS refers to a problematic law enforcement officer as “like a base-viol in a case of leather” (23). The viol is a Renaissance- and Baroque-era ancestor to the modern violin. The bass-viol is akin to the modern cello. But Shakespeare writes base – not bass. Like the decline vs. incline pun described above, this “typo” is not an accident – it contributes to our understanding of the scene. In this context, base means inferior quality, while leather symbolizes superior quality. So describing a public safety official as such illustrates how his shady behavior has been shielded through a veneer of legitimate authority. Apparently all cops were bastards even 400 years ago! There might or might not be additional, less obvious, musical references. Russ W. Duffin observes one potential connection in Shakespeare's Songbook, pointing out that four Shakespeare plays – including Errors – might allude to the Elizabethan song 'Loath to Depart' (p. 256).

Interestingly, Duffan also notes that 'Loath to Depart' is a four-part round, which in theory could continue ad infinitum, musically capturing the hesitancy to exit articulated by the title (p. 257).

In the opening scene of Errors, Egeon utters a phrase nearly identical to that song's title while describing his unfruitful search for his missing sons: Five summer have I spent in farthest Greece, Roaming clean through the bounds of Asia, And coasting homeward, came to Ephesus; Hopeless to find, yet loath to leave unsought Or that, or any place that harbors men. (132-6) It's hardly conclusive, but certainly a possibility that Shakespeare intended this connection. And even if he never intended it, the parallel is still present Though none of them have secured a spot in the standard repertoire, history contains several operas and musicals based on The Comedy of Errors. Among the better-known adaptations are Stephen Storace's 1786 opera buffa Gli Equivoci, Henry Bishop's 1819 opera The Comedy of Errors, and Richard Rodgers' and Lorenz Hart's 1938 musical The Boys From Syracuse. It appears that the main reason Storace's opera is still remembered today has less to do with its own merits than the fact that he was a pupil of Mozart, and the libretto was written by Lorenzo Da Ponte, who collaborated with Mozart on Don Giovanni, The Marriage of Figaro, and Cosi Fan Tutte – all of which have entered the standard rep. Bishop's opera is peculiar because its overture and 14 musical numbers draw from Shakespeare's writings (and one Marlowe poem – apparently Bishop falsely attributed it to Shakespeare), but has no apparent connection to The Comedy of Errors except for its title and character names (but not character actions):

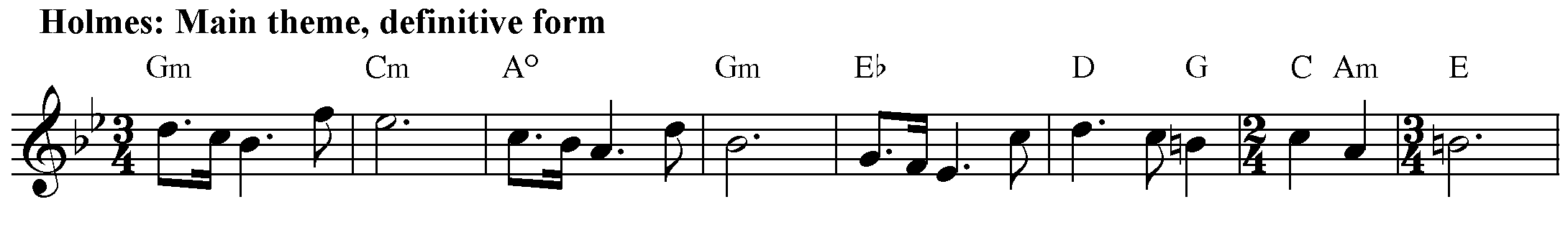

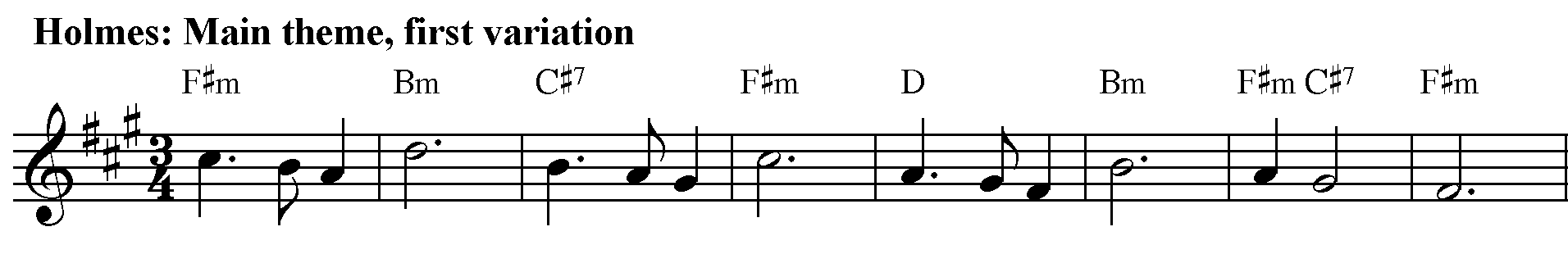

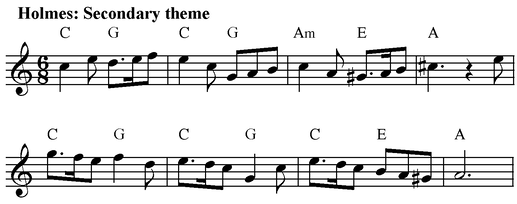

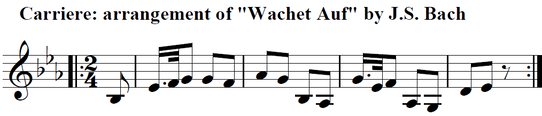

Third, Rodgers and Hart's The Boys From Syracuse is clearly based on The Comedy of Errors. Though it takes some significant departures from Shakespeare, it also adds some interesting symbolism absent from the original. As Irene Dash writes in Shakespeare and the American Musical, Hart's lyrics to 'Falling in Love with Love' features “love's blindness intrud[ing] on the romantic notion. … [L]ove makes us unable to see a lover clearly; we must struggle for hints of his reality” (p. 29): I fell in love with love one night When the moon was full I was unwise with eyes Unable to see I fell in love with love With love everlasting But love fell out with me Though Shakespeare explores the “love is blind” notion elsewhere (The Merchant of Venice: 2.6.36, A Midsummer Night's Dream: 1.1.234 & 5.1.4-22, Romeo and Juliet: 2.3.67-8, and Sonnet 148) he somewhat surprisingly does not pursue that idea in Errors, where it could nicely supplement the themes of romantic attachment and mistaken identity. Lastly, how have composers written music to accompany performances of The Comedy of Errors? Obviously, with covid19 quarantine in place, I can't attend any live performances. But, I discovered and watched two video recordings: The first was the BBC's 1983 production, directed by James Cellan Jones, with music by Richard Holmes; the other a 1989 performance by The Stratford Festival of Canada, directed by Richard Monette, with music by Berthold Carriere. Holmes' score employs two recurring themes. His main theme is heard only three times in its definitive form (at the very beginning, during the scene change from 4.4-5.1, and at the very end). However it resurfaces in disguise frequently. The first variation – clearly related in rhythm and harmony, though it has a completely different cadence – is heard between 1.2-2.1, and as intermission segues to 4.1. A second variation is heard as 3.1 transitions to 3.2. There's also a Rennaissnace-esque secondary theme that shares similarities in its cadences to the definitive version of the main theme. It is heard three times: From 2.1-2, as 3.2 segues to intermission, and from 4.3-4. Less creative, elaborate, and involved – but no less effective – than Holmes, Carriere's score is based on arrangements of J.S. Bach. While several of Bach's most famous melodies are heard throughout, a swung up-tempo rendition of the tune from his Cantata 140 “Wachet Auf” serves as the play's principal theme. Were I to compose music for Errors, I'd write a memorable main theme in two distinct tonalities – perhaps E major after Ephesus and E-flat major after Syracuse (S being German for E-flat) – to capture the whimsical nature of the story and its theme of mistaken identity. But I wouldn't try to do to much – the music would be limited to scene changes, and there'd be little underscoring. The danger of doing anything more sophisticated is that the play is already confusing enough – there's no reason to complicate further! I'd write snippets based on that main theme for each of the following:

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Shakespeare BlogA workshop for developing thoughts on William Shakespeare's writings. ArchivesCategories

All

|

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed