|

My freshman high school English class read Romeo and Juliet. Each student had to make a final project of our choice. My final project for that unit was to compose a piano solo theme for the play. And my friend Sean Braunhausen (Sean, if you ever read this, get in touch!), who was also musically inclined, made a soundtrack of different pieces that were not composed with Shakespeare in mind, but nevertheless captured the personalities of the characters. If/when I ever teach a “Music and Shakespeare” class, one of the first assignments will be to create a similar soundtrack. Though it's a relatively low-level task, it forces you to think about character motivations and identities, and how those traits might be portrayed musically. Here is my soundtrack for A Midsummer Nights Dream, with one piece of music per major character:

0 Comments

To document and track how music is employed in Shakespeare plays, I've designed a "scene chart" for each one (according to The Riverside Shakespeare's number of scenes), to be printed and filled in by a viewer/listener:

1.1

Theseus, Duke of Athens, will marry Hippolyta in four days. Their marriage might or might not be consensual on her part. “I woo'd thee with my sword,” Theseus explains ominously and ambiguously, “And won thy love doing thee injuries; but I will wed thee in another key” (16-8). It seems their relationship has had a problematic past, yet an optimistic future. This will tie in to the secondary plot of the four lovers. Meanwhile, Egeus is furious with Hermia (his daughter), who refuses to marry Demetrius (the man Egeus wants her to marry), instead preferring Lysander. Egeus accuses Lysander of “bewitch[ing] the bosom of my child. … With cunning hast thou filch'd my daughter's heart, / Turn'd her obedeience (which is due to me) / To stubborn harshness.” (27, 36-8) He calls upon “the ancient privilege of Athens” that “she is mine, I may dispose of her; / Which shall be either to this gentleman, / Or to her death” (41-4). Egeus' motivation (why would he prefer his daughter's death over her marrying the man of her choice?) is not clear. “I would my father look'd but with my eyes” (56), Hermia complains, foreshadowing Oberon's elixir that will has power to do just that. But Theseus sides with Egeus. “Rather your eyes must with his judgment look”, he insists. “[P]repare to die / For disobedience to your father's will, / Or else to wed Demetrius” (57, 86-88) After all but Lysander and Hermia exit, he tries to comfort her with one of the most famous lines of the play: “The course of true love never did run smooth” (134). But no amount of consoling can mitigate her pain. “Oh hell, to choose love by another's eyes” (140), she moans, again foreshadowing Oberon's magic potion. Facing either their loss of love or her loss of life, Lysander proposes they runaway together. He talks of his wealthy widowed aunt, who lives about 25 miles away. “There, gentle Hermia, may I marry thee”, he plans. “And to that place the sharp Athenian law / Cannot pursue us.” (161-3) This quote helps us understand why Shakespeare set Midsummer in Athens – because Athens has a long and storied history of intellectual thought and process of law. Plato's The Laws (ca. 350 BC), for example, remains a classic read on political philosophy, more than two millennia after its writing. But it's precisely that history and process that impinges upon the young lovers, thus they flee Athens to get away from its impositions. They hatch a plan to “Steal forth thy father's house to-morrow night, / And in the wood … There will I stay for thee. (164-8) In this play (and many other Shakespeare plays, including As You Like It and The Merchant of Venice), the rural provides a much-needed emotional counterbalance to urban rationality. As Hermia and Lysander finalize their escape plan, Helena (Hermia's childhood friend) enters. Helena is in love with Demetrius (who despises her), and begs Hermia to “teach me how you look, and with what art / You sway the motion of Demetrius' heart.” (192-3) Their rapid fire couplets reveal the arbitrary (to outsiders) ardor that afflicts many young lovers: Hermia: I frown upon him; yet he loves me still. Helena: O that your frowns would teach my smiles such skill. Hermia: I give him curses; yet he gives me love. Helena: O that my prayers could such affection move! Hermia: The more I hate, the more he follows me. Helena: The more I love, the more he hateth me. Hermia: His folly, Helena, is no fault of mine. Helena: None by your beauty; would that fault were mine! (194-201) In a moment of feminine confidentiality, Hermia informs Helena of her plan to elope with Lysander. During a scene-concluding monologue, Helena hatches her own plan: She will tell Demetrius of Hermia's escape in an effort to attract Demetrius' amorous attention. 1.2 In a tertiary plot commonly called “the rude mechanicals” (as Shakespeare calls them in 3.3.9), Peter Quince leads his friends Snug, Bottom, Flute, Snout, and Starveling in a discussion as they brainstorm ideas “to play in our enterlude before the Duek and the Duchess, on his wedding-day” (5-7). In one of many “plays within the play” to be found in Shakespeare, they agree to perform The most lamentable comedy and most cruel death of Pyramus and Thisby for the occasion, and assign the roles: Bottom will play Pyramus, Flute will play Thisby, Starveling will play Thisby's mother, Snout will act Pyramus' father, Quince takes Thisby's father, and Snug will play a lion. They all agree to convene “in the palace wood, a mile without the town, by moonlight; there will we rehearse; for if we meet in the city, we shall be dogg'd with company” (101-4). Just as Hermia and Lysander wished to avoid the city, so, too, do these amateur actors. Their paths, of course, will soon cross. 2.1 The quaternary and final plot line introduces the fairies of the woods. The first to appear is Robin Goodfellow, nicknamed Puck. He speaks with an unnamed fairy colleague, explaining that fairy king Oberon and fairy queen Titania are fighting over possession of “A lovely boy stolen from an Indian king” (22). King and queen soon enter, and continue their bickering on stage. “I do but beg a little changeling boy, / To be my henchman” (121-2), bellows Oberon. Titania explains the child is an orphan, and she has adopted him. “I will not part with him”, she replies, infuriating Oberon, “Not for thy fairy kingdom.” (137, 144) It is never explained why Oberon wants such a boy to be his henchman. He has, after all, far more capable servants in his fairy underlings, including Puck. In any case, Oberon now seeks revenge on his wife for refusing his demands, and he commands Puck to fetch a magic flower, “The juice of it on sleeping eyelids laid / Will make or man or woman madly dote / Upon the next live creature that it sees.” (170-2) Oberon plans to paint Titania's eyes with the potion while she sleeps, causing her to fall hopelessly in love with whatever she sees upon waking, “Be it on lion, bear, or wolf, or bull, / On meddling monkey, or on busy ape” (180-1). While she's distracted, he can steal the child. Suddenly, Demetrius enters, followed closely by Helena. She has followed her plan to tell him about Hermia and Lysander's flee from Athens, and, just as she predicted, Demetrius is now searching for his betrothed. But her plan to be alone with him as they wander through the forest backfires. “[G]et thee gone, and follow me no more”, he says in no uncertain terms. “I do not nor I cannot love you” (194, 201). In one of the most complicated and uncomfortable passages of the play, Helena reveals masochistic proclivities: And even for that do I love you the more: I am your spaniel; and, Demetrius, The more you beat me, I will fawn on you. Use me but as your spaniel; spurn me, strike me, Neglect me, lose me; only give me leave, Unworthy as I am, to follow you. … I'll follow thee and make a heaven of hell, To die upon the hand I love so well. (202-7, 243-4) How are we to make sense of these words? One novel interpretation is found in Jillian Keenan's 2016 memoir Sex with Shakespeare. Keenan wonders if Helena is sexually kinky, while Demetrius is vanilla – and that's why they are incompatible. “What if this portion of Helena's dialogue isn't silly self-debasement?” Keenan writes in her opening chapter. “What if it is instead the most explicit and brave declaration of sexual consent in the Shakespearean canon?” (p. 19). Oberon, overhearing their confidential conversation, decides to use some of his potion to help. “[A]noint his [Demetrius'] eyes,” he instructs Pucks, “But do it when the next thing he espies / May be the lady [Helena].” (261-3) What could possibly go wrong? 2.2 In another part of the forest, Titania's fairy servants sing her to sleep, and Oberon applies the potion to her eyelids, with the words “Wake when some vile thing is near.” (34) Just then, Lysander and Hermia enter, exhausted, and prepare to sleep. After they drift off, Puck applies potion to Lysander's eyelids, mistaking him for Demetrius. Then Helena and Demetrius enter and find Lysander and Hermia still snoozing. Worried Lysander might be dead, Helena wakes him, whereupon the potion takes effect, and Lysander falls in love with Helena. “[N]ature shows art,” he serenades Helena, “That through thy bosom makes me see thy heart. … Not Hermia, but Helena I love. / Who would not change a raven for a dove?” (104-5, 113-4) Unaware of the magic at play, Helena is offended that Lysander would so betray Hermia. “[I]s't not enough, young man,” she scolds him, “That I did never, no, nor never can, / Deserve a sweet look from Demetrius' eye, / But you must flout my insufficiency?” (125-9) 3.1 Meanwhile, the rude mechanicals debate how to best present their performance. Puck stumbles upon them and decides to have some fun by turning Bottom's human head into that of an ass. Unaware of his new donkey noggin, he can't understand why his friends all run away from him in terror. Left alone, he sings to himself and wanders through the forest, where he stumbles upon the sleeping Titania, and rouses her. “What angel wakes me from my flow'ry bed?”, she asks, as the potion does its job. I pray thee, gentle mortal, sing again, Mine ear is much enamored of thy note; So is mine eye enthralled to thy shape; And thy fair virtue's force (perforce) doth move me On the first view to say, to swear, I love thee. (129, 137-41). At first, Bottom is confused by this amorous attention. “Methinks, mistress, you should have little reason for that”, he admits. “And yet, to say the truth, reason and love keep little company” (142-4) And so, not one to refuse the romantic advances of a beautiful woman, he plays along. 3.2 Oberon wonders aloud what happened to Titania, and with what creature she has fallen in love. Puck arrives, telling him, “My mistress with a monster is in love. … Titania wak'd, and straightway lov'd an ass.” (6, 34) And when Oberon asks about Demetrius, Puck claims, “I took him sleeping (that is finish'd too)” (38), neither yet realizing Puck's error. But the truth comes out when Demetrius and Helena enter. “This is the woman”, Puck confirms, “but not this the man.” (42) Lysander and Helena arrive a moment later, and the four bicker back and forth at some length, while the two fairies, hidden from view, observe their banter. Oberon resolves to use the potion again to restore order. “When they next wake,” he says, “all this derision / Shall seem a dream”. (370-1). 4.1 At some point between acts 3 and 4, Oberon asks Titania for the changeling boy off stage, whom she readily gives up. On stage, Titania, still governed by the potion, continues doting on Bottom, whose head is still that of a donkey's. “Her dotage now I do begin to pity”, Oberon admits, as he watches from a distance. “Now I have the boy, I will undo / This hateful imperfection of her eyes.” (62-3) He also instructs Puck to restore Bottom's human head. A moment later, Theseus, Hippolyta, and Egeus appear and spot the four young lovers still asleep on the ground. “[I]s not this the day”, Theseus addresses Egeus, “That Hermia should give answer of her choice?” (135-6) They wake them, and Theseus demands Hermia's decision, but Demetrius (who was just potioned) intervenes. “[M]y love to Hermia / Melted as the snow”, he concedes, potion taking effect. “The object and the pleasure of mine eye, / Is only Helena.” (165-6, 170-1) Pleasantly surprised at his sudden change of heart, Theseus invites both young couples to join his own wedding celebration: “[I]n the temple, by and by, with / These couples shall eternally be knit.” (180-1) Everybody exits except the still-sleeping and now human-headed Bottom. He wakes, uncertain of how he got here, and wonders if the fantastical events he remembers were real or imagined. He assumes the latter, and that nobody could make sense of it. “Man is but an ass,” he concludes, “if he go about t' expound this dream.” (206-7) He gives it no more thought, and exits in search of his friends. 4.2 Meanwhile, in Quince's house, the other rude mechanicals worry about Bottom, since nobody has seen him since their rehearsal in 3.1. They will not be able to perform Pyramus and Thisby without him. When he shows up safe and sound, everybody is overjoyed, and they all agree to perform as originally planned. 5.1 In the aftermath of the three off-stage weddings, Theseus calls for entertainment. “What revels are in hand?”, he asks. “Is there no play / To ease the anguish of a torturing hour?” (36-7) Why Theseus considers his own wedding torturous is unclear. He selects the rude mechanicals' Pyramus and Thisby from a list of options, and the lengthy “play within the play” commences. “This is the silliest stuff that ever I heard” (210), Hippolyta comments as she watches – a phrase that could just as easily describe A Midsummer Night's Dream. Play complete, everybody engages in a celebratory dance. After the human characters exit, the fairies enter one last time and launch into their own song and dance, and Puck offers a concluding soliloquy: “You have but slumber'd here / While these visions did appear. / And this weak and idle theme, / No more yielding but a dream” (5.1.425-9). King Henry: "What treasure, uncle?" Exeter: "Tennis balls, my liege." William Shakespeare, Henry V, act 1, scene 2 Using that quote as a springboard, I interrupt my considerations of Shakespeare's plays to visit the ever-so-tangentially-related topic of tennis. The other day I recorded myself throwing tennis balls, serving tennis balls, and throwing baseballs at distances of 10, 15, 20, and 25 feet. Knowing the footage was shot at 30 frames per second (I did confirm that by recording a stopwatch) allows me to calculate the speed with reasonable accuracy. The slides below can serve as an example: The ball traveled 20 feet (note the measuring tape) in 5 frames (1/6 of a second), equating to 120 feet per second (20*6), or about 82 mph (120/1.467). Here is a summary of the results:

And here's the spreadsheet, with all the hard data:

It's astonishing to think professional baseball pitchers can throw twice as fast, or that elite tennis players regularly serve 50% faster - and both with far more accuracy than I'll ever have!

Obviously, this test not flawless - it does not address aim (a tennis serve is worthless if it doesn't land in the service box), and footage with more frames per second would increase the precision of the math - but it gives a pretty good estimate. 1.1 The play begins with the wealthy title character, Antonio, depressed. “I know not why I am so sad” is his famous opening line. His friends Salerio and Solanio attempt to comfort him. “Your mind is tossing on the ocean” (8), observes Salerio, foreshadowing the sinking of Antonio's fleet in 3.1. Solanio wonders if he might be in love, though Antonio quickly dismisses the notion (46-8). But, as we'll see (and as is played up in many modern productions), there is a strong current of homoeroticism between Antonio and Bassanio throughout Merchant (and many other Shakespeare plays) that cannot be so easily refuted. Might Antonio's quick denial of being in love mask homosexual desires that he doesn't want to admit? Shortly after Solanio's amorous inquiry, Bassanio, Antonio's “most noble kinsmen” (57), enters along with friends Lorenzo and Gratiano, who invite Antonio to dinner later that evening (70-71). A moment later, Antonio and Bassanio are left alone on stage. “To you, Antonio,” Bassanio admits, “I owe the most in money and in love,” (130-1). There is no explicit evidence that “love” in this case means anything other than “Platonic friendship”, though it's not difficult to infer implicit intimacy into this scene. However, Bassanio then reveals his romantic interest in Portia, a wealthy heiress in Belmont. It is unclear to what extent Bassanio's interest in Portia is genuine affection vs. gold digging – is he sincerely in love, or just after her fortune? We learn in the following scene (1.2.112-21) that they have met at least once before, and recall each other fondly. But Bassanio also frames his courtship as a plan for “How to get clear of all the debts I owe.” (130-4). Straightforwardly or otherwise, if Bassanio is to pursue Portia, he'll need more money to compete with her many other suitors. “[B]e assur'd”, consoles Antonio, “My purse, my person, my extremenst means / Lie all unlock'd to your occasions” (137-9). However, “all my fortunes are at sea / Neither have I money nor commodity / To raise a present sum; therefore go forth / Try what my credit can in Venice do.” (177-80) 1.2 The scene switches to Belmont, where Portia and her attendant, Nerissa, discuss her marital situation. “I may neither choose who I would, nor refuse who I dislike”, she complains. “[S]o is the will of a living daughter curb'd by the will of a dead father.” (23-5) Before his death, Portia's father devised a game in which potential spouses must guess between three caskets – one gold, one silver, one lead. Hidden in one of them is Portia's portrait (note the similarity between those words). If guessed correctly, he wins Portia as a wife. Nerissa lists several suitors from all over Europe, whom Portia mocks mercilessly, until Nerissa asks, “Do you not remember, lady, in your father's time, a Venetian, a scholar and a soldier[?]” (113). “Yes, yes, it was Bassanio”, Portia responds enthusiastically. “I remember him worthy of thy praise.” (115-6 & 120-1) Why does Nerissa mention Portia's father in this context? Might Bassanio have been Portia's father's choice to marry her? But Portia's momentary relief at the mention of Bassanio is short-lived, for just then a servant enters to notify Portia that “the Prince of Morocco … will be here to-night.” (125-6) Reminded again of her lack of marital choice, she hangs her head in disappointment and sulks off stage. 1.3 Back in Venice, Bassanio negotiates with Jewish moneylender Shylock. They agree to a loan of “Three thousand ducats for three months, and Antonio bound.” (9-10). The term “bound” in this case has multiple meanings: Not only is Antonio agreeing to pay back the money, but it also foreshadows his physical binding in 4.1 after he fails to pay. Antonio enters, prompting an aside from Shylock. “I hate him for he is a Christian[.] …He hates our sacred nation[.] … Cursed be my tribe if I forgive him!” (42, 48, 51-2). Clearly they have a history of animosity, as Antonio is extremely antisemitic. “You call me misbeliever, cut-throat dog, / And spet [spit] upon my Jewish gaberdine”, he accuses Antonio. But “now it appears you need my help.” (111-4) What is going through Shylock's mind in this scene? His easiest and safest choice would be refusing to lend the money in the first place. After all, he admits “I cannot instantly raise up the gross[.] … Tubal, a wealthy Hebrew of my tribe, / Will furnish me.” (55-8) Shylock's lack of immediate access to the money results in a chain of borrowing: Bassanio borrows from Antonio, who borrows from Shylock, who borrows from Tubal. But Shylock does accept the bond – and the extra work that comes along with it. Why? What's in it for him? The obvious answer is revenge. At what point does revenge dawn on Shylock? Is it right away, at the start of the scene? Or might Antonio inadvertently instigate this vengeance? “I am as like to call thee so again,” Antonio retorts sardonically to Shylock's accusations, “To spet on thee again, to spurn thee too.” (130-1) One way or the other, Shylock responds with insincere amity. “I would be friends with you, and have your love,” he insists. “Forget the shames that you have stain'd me with” (138-9). Only when Antonio defaults do we come to realize that Shylock's friendly words were deceptive – he never had any friendly intent, only retribution. Under the guise of humorous absurdity, Shylock suggests as most unusual and cruel punishment should Antonio fail to reimburse: If you repay me not on such a day, In such a place, such sum or sums as are Express'd in the condition, let the forfeit Be nominated for an equal pound Of your fair flesh, to be cut off and taken In what part of your body pleaseth me. (146-51) And Antonio is more amused than fearful at the proposition. “Content, in faith, I'll seal to such a bond,” he assents, “And say there is much kindness in the Jew.” (152-3) Antonio will be much less jovial in 4.1, when Shylock actually sharpens his knife! Shylock has been the most dynamic character in the long history of performances of The Merchant of Venice. The Royal Shakespeare Company details that history, and how Shylock has been portrayed over the centuries. What started as a comedic role assumed more dramatic and compelling interpretations, especially after the horrors of the Holocaust in the mid-twentieth century. 2.1 Back in Belmont, the Prince of Morocco arrives. “[L]ead me to the caskets / To try my fortune” (23-4), he confidently proclaims. (Ironic that he uses the word “lead”, when the correct casket is the one made of “lead”!) But before she does so, Portia raises the stakes of the game. “[I]f you choose wrong,” she warns, “Never to speak to lady afterward / In way of marriage” (40-1) Undaunted, the Prince proceeds. 2.2 The clown Launcelot Gobbo appears on stage, alone. He speaks of “this Jew my master” (2), meaning Shylock, who consistently mistreats him. When his father, Old Gobbo enters, they together discuss the pros and cons of abandoning his master. “Certainly the Jew is the very devil incarnation,” Launcelot concludes. “I will run … for I am a Jew if I serve the Jew any longer.” (27-8, 31, 112-13) From now on, he will work as Bassanio's servant, instead. Meanwhile, Gratiano wishes to travel with Bassanio to Belmont. Bassanio consents, though not without a stern warning “To allay with some cold drops of modesty / Thy skipping spirit, lest through thy wild behavior / I be misconst'red in the place I go to, / And lose my hopes.” (186-9) 2.3 Shylock's daughter, Jessica, is the last major character to be introduced. Apparently she and Launcelot have been talking candidly off-stage, for her scene-opening line expresses sorrow over his decision that “thou wilt leave my father so. / Our house is hell, and thou, a merry devil, / Didst rob it of some taste of tediousness.” (1-3) Launcelot's abandonment of Shylock might inspire Jessica's own, for she gives him a letter to deliver to Lorenzo, her secret lover. “O Lorenzo,” she pleads in a brief scene-ending monologue, “If thou keep promise, I shall end this strife, / Become a Christian and thy loving wife.” (19-21) 2.4 Launcelot dutifully delivers Jessica's letter to Lorenzo. “She hath directed”, he explains upon reading it, “How I shall take her from her father's house” (29-30). 2.5 Shylock, having been invited to dinner by Bassanio, leaves Jessica home alone, with strict restrictive orders: Lock up my doors, and when you hear the drum And the vile squealing of the wry-neck'd fife Clamber not you up to the casement then, Nor thrust your head into the public street To gaze on Christian fools with varnish'd faces; But stop my house's ears, I mean my casements; Let not sound of shallow fopp'ry enter My sober house. (29-36) Shylock's anti-music proclivities correlate him with other anti-music Shakespearean characters, most notably Cassius from Julius Caesar, who “loves no plays, … hears no music; [and] Seldom he smiles” (1.2.203-5). This will resurface in 5.1. “Farewell,” Jessica bids her father in a scene-concluding couplet, “and if my fortune not be cross'd / I have a father, you a daughter, lost.” (56-7) 2.6 Lorenzo, with assistance from Gratiano and Salerio, arrives at Shylock's house, where Jessica, disguised in boys' clothing, is awaiting rescue. She takes a “casket” full of her father's most precious valuables as she flees. In one of the most interesting passage of the whole play, she comments, “I am glad 'tis night, you do not look on me, / For I am much asham'd of my exchange.” (34-5) But what does she mean by “exchange”? She could be referring to her eloping – the illegitimate exchange of her residence. Or perhaps to her theft of her father's jewels. Or maybe to her “gender exchange”, being a female character dressed as a male. Or possibly all of those things at once. “But love is blind, and lovers cannot see / The pretty follies that themselves commit,” she continues. “For if they could, Cupid himself would blush / To see me thus transformed to a boy. (36-9) Jessica is self-conscious about her love for Lorenzo while cross dressing, as they would appear to be a gay male couple to any unknowing observer. This gender bending and homophobia reinforces the homoerotic tension already present between Antonio and Bassanio. 2.7 Portia presents the Prince of Morocco with the three caskets, instructing him to make his choice. Each is adorned with an inscription. The gold reads, “Who chooseth me shall gain what many men desire” (5); the silver reads, “Who chooseth me shall get as much as he deserves” (7); the lead, “Who chooseth me must give and hazard all he hath” (9). He chooses gold, but departs in agony when it turns out to be incorrect. 2.8 Salerio and Solanio mock Shylock's misfortunes and discuss “A vessel of our country richly fraught” (30) that “miscarried” (29) in the English Channel, foreshadowing the fate of Antonio's own ships. 2.9 Yet another suitor, the Prince of Arragon, arrives in Belmont. He selects the silver casket, and departs disappointed. The scene closes with news of Bassanio's arrival, with “Gifts of rich value” (91), which brightens Portia's mood considerably. 3.1 Solanio and Salerio are talking once more, this time “that Antonio hath a ship of rich lading wrack'd on the Narrow Seas” (1-3), fulfilling the foreshadowing we saw in 1.1 and 2.8. Shylock enters, lamenting the loss of his daughter. “She is damn'd for it”, he wails, “My own flesh and blood to rebel!” (31, 34) It's hard for an audience not to feel sympathy for him, especially as Solanio and Salerio ridicule him ruthlessly. “There is more difference between thy flesh and hers than between jet and ivory,” the latter taunts, “more between your bloods than there is between red wine and Rhenish [white wine].” (39-42) Their conversation quickly moves on to Antonio and his recently lost ship. “I am sure if he forfeit thou wilt not take his flesh”, Salerio proclaims. “What's that good for?” (51-2) “[I]f it will feed nothing else, it will feed my revenge” (53-4), Shylock responds ominously, before launching into one of the most famous speeches of the play, and one of the most poignant speeches in all of Shakespeare: He hath disgrac'd me, and hind'red me half a million, laugh'd at my losses, mock'd at my gains, scorn'd my nation, thwarted my bargains, cool'd my friends, heated mine enemies; and what's his reason? I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes? Hat not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions; fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, heal'd by the same means, warm'd and cool'd by the same winter and summer, as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh?If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you teach me, I will execute (54-72). It's this scene – and this passage specifically – that precludes a completely comedic or thoroughly villainous interpretation of his character.

Fellow Jew Tubal (who, you'll recall, Shylock mentioned in 1.3) arrives with news of Jessica. “Your daughter spent in Genoa, as I hard, one night fourscore ducats,” he relates, as Shylock cringes. “One of them show'd me a ring that he had of your daughter for a monkey” (108-9, 118-9). It's unclear if the term “monkey” refers to a literal animal, for which she exchanged the ring, or if that is a metaphor – perhaps Elizabethan slang, the significance of which is lost on modern audiences. In any case, the only comforting news Tubal bears to Shylock is confirming that Antonio's ships have indeed sunk, and thus “Antonio is certainly undone.” (124) 3.2 Having witnessed the Prince of Morocco choose the gold casket in 2.7, and the Prince of Arragon select silver in 2.9, we the audience know the correct casket must be the lead one. But Bassanio doesn't know that, as he prepares to make his decision. As he deliberates, Portia orders, “Let music sound while he doth make his choice” (43). Curiously, the song sung while Bassanio deliberates opens with three lines, all of which rhyme with the correct answer: Tell me where the fancy bred, Or in the heart of in the head? How begot, how nourished? (63-6) Portia made no such command for either of the previous suitors, and she clearly wishes to marry Bassanio, so might this be her way of tilting the odds in her favor? Whether or not Bassanio heeds her hint, he correctly selects the lead casket, and thus wins Portia's hand in marriage. Ecstatic, Portia gives Bassanio a ring, “Which when you part from, lose, or give away, / Let it presage the ruin of your love” (172-3). Gratiano, meanwhile, has developed a parallel affection for Nerissa. “My eyes, my lord, can look as swift as yours”, he asserts. “You saw the mistress, I beheld the maid.” (197-8) Nerissa happily reciprocates his ardor, and at some point gives him a ring, too (it comes up in 4.2), though apparently off stage. But their celebration is cut short when a telegram arrives notifying Bassanio that Antonio has failed to pay back their loan. “Here are a few of the unpleasant'st words / That ever blotted paper!” (251-2), he bemoans to Portia. When she realizes the amount is only three thousand ducats, she's shocked that it's so low. “What, no more?”, she asks. “Pay him six thousand, and deface the bond. … First go with me to church and call me wife, / And then away to Venice to your friend” (298-9, 303-4). 3.3 Meanwhile, back in Venice, Antonio attempts to reason with Shylock to avoid the harsh penalty for failing to pay back the loan. But Shylock will have none of it. “I'll have my bond”, he insists, “I will not hear thee speak.” (12) And Antonio realizes that Shylock's friendly face from 1.3 was just a facade. 3.4 Portia gets the zany and legally dicey idea to impersonate the judge adjudicating between Shylock and Antonio, thereby saving Antonio's life. She sets her plan in motion by lying to Lorenzo: I have toward heaven breath'd a secret vow To live in prayer and contemplation, Only attended by Nerissa here, Until her husband and my lord's return. There is a monast'ry two miles off, And there we will abide. (27-32) She also instructs her servant Balthazar to deliver a letter she has written to one Doctor Bellario in Padua. 3.5 In perhaps the most unnecessary scene of the play, Launcelot warns Jessica that she might have trouble getting into heaven because “the sins of the father are to be laid upon the children” (1-2), despite her conversion to Christianity. Lorenzo arrives and tells Launcelot to back off, rebuking him for impregnating a black woman out of wedlock. After Launcelot exits, Jessica speaks of her deep admiration for Portia, though they have only met once (in the previous scene). 4.1 In a Venetian courtroom, the Duke encourages Shylock to “show thy mercy” (20), yet he refuses. When Bassanio also encourages mercy, Shylock answers, “I am not bound to please thee with my answers.” (65) And when Bassanio offers six thousand ducats – double the original amount – Shylock still declines. “How shalt thou hope for mercy, rend'ring none?” (88), asks the Duke, foreshadowing that the tables will soon turn on Shylock. But again he refuses. “What judgment shall I dread,” Shylock responds, “doing no wrong? … If you deny me, fie upon your law!” (89, 101) Meanwhile, Nerissa, disguised as a lawyer's clerk, brings a letter from Doctor Bellario “commend[ing] / A young and learned doctor to our court. … His name is Balthazar.” (143-4, 154). But Balthazar (not to be confused with Portia's servant of the same name) is actually Portia impersonating a legitimate lawyer. She, too, first attempts to talk Shylock into mercy, then into accepting several times the loan amount. But Shylock refuses every offer. “There is no power in the tongue of man / To alter me” (241-2), he maintains. Quickly realizing that any such attempts to talk sense into Shylock will fail, Portia changes tactics, instead adopting a paralyzing hyper-literal interpretation of the contract: Since the bond makes no mention of blood, she says, should Antonio bleed “one drop” during the flesh-ectomy, “thy lands and goods / Are by the laws of Venice confiscate” (310-1) on the grounds that Shylock has failed to follow the contract. Furthermore, she continues, since the contract explicitly states “a pound of flesh”, should Shylock should remove any more or less than exactly one pound, “Thou diest, and all thy goods are confiscate.” (332) Realizing his sticky situation, Shylock reluctantly agrees to accept the reimbursement of the original three thousand ducats. But Portia shoots him down again. “He shall have merely justice and his bond.” (339), she declares. Shylock, defeated and dejected, prepares to leave. But Portia intervenes yet again. If it be proved against an alien, That by direct or indirect attempts He seek the life of any citizen, The party 'gainst the which he doth contrive Shall seize one half his goods; the other half Comes to the privy coffer of the state. And the offender's life lies in the mercy Of the Duke only. ... Thou hast contrived against the very life Of the defendant. … Down therefore, and beg mercy of the Duke. (347-63) In an ironic twist, Portia forces Shylock to do precisely what she begged of him only moments earlier. Shylock is stunned at the sudden and severe change of events. “You take my house when you do take the prop / That doth sustain my house”, he complains. “[Y]ou take my life / When you do take the means whereby I live.” (375-8) But the back-breaking blow comes a moment later, when Antonio adds “He [must] presently become a Christian” (387). Having lost his daughter, his valuables, and his loan, he now looses his religion, too. He loses everything dear to him. In short, he loses his integrity and reasons for living. It appears that Shakespeare intended this scene (indeed, the whole play) to be funny. After all, it was listed as a comedy when published in the First Folio in 1623. Moreover, Judaism was illegal in England at the time this play was written (ca. 1596-97), and had been since King Edward I's Edict of Expulsion in 1290 – one reason why the play is not set in England. There are reports of Jews living (or at least practicing) secretly in England at this time, but it seems unlikely that Shakespeare ever met any Jewish people, much less sympathized with their struggles, though no concrete evidence exists to either confirm or deny that. Courtroom drama over, Antonio and Bassanio meet with Balthazar (whom they still don't realize is actually Portia) to thank him (her), and offer gifts in thanks (nevermind the obvious conflict of interest). At first he (she) refuses any gifts, saying, “He is well paid that is well satisfied” (415). But after reconsidering, he (she) requests Antonio's gloves, and Bassanio's wedding ring. At first, Bassanio refuses to part with the ring, and Balthazar (Portia) exits. But Antonio coerces him into changing his mind. “Let his [Balthazar's] deservings and my love withal”, he coaxes, “Be valued 'gainst your wive's commandement.” (450-1) And so Bassanio gives the ring to Gatiano, with instructions to deliver it to Balthazar (Portia). 4.2 Gratiano catches up with Balthazar (Portia) and hands over the ring. Seeing Portia's manipulative power, Nerissa wonders if she can pull off the same stunt. “I'll see if I can get my husband's ring,” she confides to Portia, “Which I did make him swear to keep for ever.” (12-13) We find out in the next and final scene that she was indeed successful, albeit off stage (as was her giving of the ring in the first place). 5.1 Back in Belmont once last time, Lorenzo and Jessica sit together in the moonlight, comparing their love to famous couples throughout history. (Oddly, all the lovers mentioned end in tragedy!) Lorenzo calls for music, and declares, “The man that hath no music in himself / Nor is not moved with concord of sweet sounds, / Is fit for treasons[.] … Let no such man be trusted” (83-5, 88). This is a clear reference to Shylock's diatribe against music in 2.5.29-36. Portia and Nerissa (no longer in disguise) enter and comment favorably on the music. When Bassanio, Gratiano, and Antonio arrive a moment later, Nerissa pranks her husband by asking what happened to the ring she gave him. “I gave it to a youth,” Gratiano stammers, still not realizing the joke. “No higher than thyself, the judge's clerk, / A prating boy, that begg'd it as a fee. / I could not for my heart deny it him.” (161-5) Portia joins the ironic marital fun by saying that her man would never part with his ring. To which Bassanio sheepishly confesses, also not realizing the joke. Portia and Nerissa give “new” rings to Bassanio and Gratiano, who are shocked to find they are the same rings in question. In one final joke, the two women claim that they obtained back the rings by having sex with the doctor and his clerk, rendering both men cuckolds. But enough is enough, and they finally reveal the truth: That Portia was the doctor, and Nerissa the clerk. Finally recognizing the gag, Gratiano takes the play's final lines: “[W]hile I live I'll fear no other thing”, meaning another man, “as keeping safe Nerissa's ring.” (306-7) I've made no attempt to hide my admiration for Richard II. One reason I find it so compelling is for how its musical imagery helps tell the story. In his essay Music of the Elizabethan Stage, John Stevens notes “an increasing subtlety in the use of music to ... reinforce the weakness, the inner collapse of Richard” (p. 17). At the start of the play, Richard, as king, wields authority – both political and musical. “The trumpets sound” for “his Majesty's approach” in 1.3. And just as Bullingbrook and Mowbray are about to battle, “A charge sound[s]” as “the King hath thrown his warder down” (line 18). “Let the trumpets sound”, Richard orders, “While we return these dukes what we decree”, followed by “A long flourish” (121-2). When he returns, he speaks of “boist'rous untun'd drums, / With harsh-resounding trumpets' dreadful bray” before banishing both combatants (134-5). The musical symbolism of Richard's jurisdiction is furthered by Mowbray, who protests, now my tongue's use is to me no more Than an unstringed viol or a harp, Or like a cunning instrument cas'd up, Or being open, put into his hands That knows no touch to tune the harmony (161-5). In each of these instances, Richard imposes his will – and his music – on others. But by the end of the play, when Richard has lost all power, this musical symbolism is reversed. Shortly before his murder in 5.5, Richard laments, “Music do I hear? / Ha, ha, keep time! How sour sweet music is / When time is broke, and no proportion kept” (41-3). One of music's fundamental components, rhythm refers to the duration of sounds and the proportional relationships between them. When those proportions aren't properly maintained, rhythmic chaos reigns. The most interesting part about this scene, however, is questioning if this “sour music” is real: Is Richard actually hearing poorly performed music, or is the music perfectly played and thus its distortion is only in his mind? (This has obvious parallels to the ghost in Hamlet.) If the former, then Richard's (and Hamlet's) grasp on reality is still strong; if the latter, it implies Richard's (and Hamlet's) descent into insanity. The handling of this scene and is one of the important musical choices a director must make. Three of the six productions I've found have employed music that does keep time properly. I have not been able to find a single production in which the “sour music” is actually sour (meaning clearly rhythmically problematic), though two of the six (described momentarily) are rhythmically ambiguous. In the YouTube video below (Brussels Shakespeare Society, 2012, directed by Charles Bouchard, composer unknown), solo guitar music is heard at 2:13:22, and is well-performed (clearly with correct and well-proportioned rhythm). In this second YouTube video (a 1960 audio drama, neither director not composer specified), the music starts about 2:24:31, and is also well-performed. In The Hollow Crown (2012, directed by Rupert Goold, with music by Dan Jones), the music commences at 2:16:10, and is likewise well-performed. Curiously, Deborah Warner's 2016 direction, starring Fiona Shaw as the title character, does not include any music during this scene (seen at 2:03:44), perhaps implying that everything is in Richard's mind. Lastly, two productions employ a solo monophonic instrument: The Royal Shakespeare Company's 2014 production uses a recorder at 2:26:06; and the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre's audio recording a bassoon at 2:40:38. In both, the rhythms and meters are ambiguous – only the performer knows for sure how s/he is counting it mentally, but no obvious metric pattern is discernible to the audience. Richard's perception (real or imagined) of this disproportioned music inspires his ruminations on a connection between music and life: So is it in the music of men's lives. And here have I the daintiness of ear To check time broke in a disordered string; But for the concord of my state and time Had not an ear to hear my true time broke. I wasted time, and now doth time waste me (44-49). Richard sees the music as symbolic of his political mishandlings, which led to his deposition and current imprisonment. But, in true tragic form, it's too late – Richard, like the Marley brothers in Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol, recognizes his mistakes only when their rectification is beyond his grasp. Just as Richard destroyed a mirror that accurately allowed him to see himself in 4.1, he likewise calls for the music, which also provides genuine insight into his problematic self, to cease. This music mads me, let it sound no more, For though it have holp mad men to their wits, In me it seems it will make wise men mad (61-3). But music, being immaterial, cannot be as easily shattered as a tangible mirror. Moreover, even if music could be shattered, Richard no longer posses the authority to command it. “Whereas as king he had power over his trumpets, and made them express his royal will,” continues Stevens, “now another man's wish imposes this unroyal music on him and puts him into its power” (p. 18). Though Shakespeare specifies exactly where “The music plays” (line 41), he does not specify where the music stops. It seems unlikely that the music, which began with no input from Richard, would conclude upon his command, yet the script offers no explicit commentary to either support or deny that notion. The turning point for Richard's musical command – and the turning point for his power in general – comes when his uncle, John Gaunt, dies in 2.1. Prior to Richard's entrance, Gaunt comments how the tongues of dying men Enforce attention like deep harmony. … More are men's ends mark'd than their lives before. The setting sun, and music at the close As the last taste of sweets, is sweetest last (5-6 & 11-3). In other words, that which occurs at the end of something often receives more attention than that which occurs at its beginning. In this context, Gaunt means that his criticisms at the end of his life should receive more weight than any previously mentioned. But this “sweetest last” idea applies to music, too. Though not yet true in Shakespeare's day (he died in 1616), this is an accurate summary of common practice functional harmony (ca. 1650-1900). Indeed, the entire discipline of Schenkerian analysis is predicated on an elaborate prolongation of tonic that ultimately leads to a predominant-dominant-tonic cadence. The ending is where the harmonic action is – that which comes before the cadence is often of significantly less harmonic interest. After Richard's entrance, Gaunt savagely berates the king. “Thy death-bed is no lesser than thy land, / Wherein thou liest in reputation sick,” he cautions. “A thousand flatterers sit within thy crown … Which art possess'd now to depose thyself.” (95-6, 100, 108) “This scene might prove a new beginning or Richard,” writes Ted Tregear in his 2019 essay Music at the Close, “however dissolute his career so far” (p. 697). But the self-centered Richard, offended that anybody would dare criticize him, instead rejects Gaunt as “A lunatic lean-witten fool / Presuming on an ague's privilege” and proceeds to intercept Gaunt's inheritance (115-6). Failing to heed Gaunt's warning proves to be the point of no return for Richard. From then on, he suffers one breakdown after another, until he winds up imprisoned and murdered in the final act. Richard II is the story of a king's gradual loss of jurisdiction. And along the way, musical imagery is constantly present to help tell it. And here's all the boring (but important) statistical stuff. Music in Shakespeare's plays assumes three distinct roles: (1) stage directions, (2) lyrics, and (3) dialog. I've found 26 explicit musical references in the script of Richard II. Of those, exactly half are stage directions.

None of the 26 are lyrics. That leaves 13 musical references in the dialog (many of which were considered above).

Lastly, what composers throughout history have written music for Richard II, as a music drama, as incidental music to accompany a performance, or as concert works inspired by it?

There is a somewhat surprising dearth of music for Richard II. I have not been able to find any operas or musicals (or even references to them) whatsoever, though that doesn't mean none exist. Perhaps the most historically important composer to write music for RII was Englishman Henry Purcell (1659-95), who, according to Charles Cudworth in his essay Song and Part-Song Setting of Shakespeare's Lyrics, 1660-1960, composed “Retired from any mortal's sight” for Nahum Tate's 1681 Bowdlerized adaptation of Richard II re-titled The Sicilian Usurper, even though it contains “not a line by Shakespeare” (p. 56). I also stumbled upon a 2019 article from The Guardian describing the premiere recording of Ralph Vaughan-Williams' score for a radio production of RII, though I've not been able to actually hear it. The only other composer of note I've been able to connect with RII (ever so tangentially) is Aaron Copland, who collaborated with Orson Welles in 1939 on The Five Kings, an adaptation of several of Shakespeare's history plays. According to aaroncopland.com, however, the manuscript remains unpublished. There are 20 musical references in the script for Julius Caesar, 17 of which are diagetic stage directions:

Most common in Shakespeare's histories, the term alarum signals danger (an alarm), especially in the context of combat, that is often but not always musical in nature. Plenty of musical alarums exist in Shakespeare's stage directions, but plenty of not-necessarily-musical examples exist as well. In their exhaustive Music in Shakespeare: A Dictionary, Christopher R. Wilson and Michela Calore write, “The sounding of alarums by various instruments, especially trumpets, drums or bells is connected with military atmospheres” (p. 12). In Caesar, the term only appears in act 5, as the two armies battle. On the other hand, flourish indicates the entrance/departure of the most important characters. In the histories it typically designates royalty, but in Caesar it signals the title character, Brutus, and the soothsayer. Some confusion exists as to flourish instrumentation. Wilson and Calore write oxymoronically, “the flourish was invariably for trumpets or cornetts sometimes accompanied by drums. Some examples of flourishes for recorders and hautboys are also observed. In general, any instrument or instruments could play a flourish as a short (improvised) warm-up to a longer notated piece” (p. 179). Regardless, flourishes were “the most improvisatory and musically least structured” stage direction (p. 179). Edward Naylor, in his book Shakespeare and Music cites 68 instances of the term “flourish” as a stage direction in 17 of Shakespeare's plays: 22 for the entrance/exit of royalty, 12 for the entrance/exit of important non-royalty, 10 for the public welcoming of royalty or otherwise important characters, 7 to conclude a scene, 6 to indicate victory in battle, 2 to announce royal decrees, 2 to indicate entrance/exit of a governmental body (senate, tribune), and 2 to signal the approach of a play-within-the-play (p. 161). (How come that only totals 63?) “The most exclusive, least used signal in military and courtly contexts”, a sennet is similar to a flourish, but more standardized (less improvisatory) and longer in duration (Wilson and Calore, p. 376). According to Naylor, “sennet” occurs only 9 times in 8 plays – 3 to designate the entrace/exit of a Parliament, 3 for a royal procession, and 3 to signal the presence of royalty (p. 172). So there appears to be no set definition for these terms, only general patterns in their usage. It should also be noted that there is much debate whether or not Shakespeare actually wrote his own stage directions, or if they were added subsequently by editors. We will probably never know for sure, one way or the other. While most musical references in Caesar are stage directions and thus aren't necessarily Shakespeare's words, there are three other musical references scattered throughout the script that (presumably) did come from his pen:

While much music based on Julius Caesar exists, little of it bears any resemblance to Shakespeare's play. Georg Frederic Handel's Giulio Cesare, for instance, is the best-known and most frequently-performed, yet has nothing to do with Shakespeare.

Robert Schumann's 1851 Julius Caesar Overture, Op. 128 bears little resemblance to Shakespeare's play, either, though it was apparently inspired by it. In his essay 'Shakespeare in the Concert Hall', Roger Fiske articulates and addresses a two-fold challenge of programmatic music: On one hand, the composer is limited by the narrative functions s/he is supplementing; on the other, the composer must write compelling music, independent of any narrative connotations. “Only when a composer fails at both levels,” he writes, “as Schumann did in his overture to Julius Caesar, is descriptive music best left on the shelf” (p. 181). Ouch! Orson Welles famously spearheaded a 1937 production of Caesar with the Mercury Theater, featuring music by Mark Blitzstein. That production was adapted for a 11 September 1938 radio broadcast, retaining Blitzstein's score, which is available on Amazon for just $0.69. (The description falsely cites Bernard Herrmann, but the broadcast correctly credits Blitzstein.) Miklós Rózsa composed the score for a 1953 film adaptation of Shakespeare, directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz. Its entire soundtrack can be heard on YouTube. Giselher Klebe wrote a brief dodecaphonic opera titled Die Ermordung Cäsars [The Murder of Caesar], Op. 32 in 1959, with a libretto by August Wilhelm von Schlegel based on Shakespeare. In his essay 'Shakespeare and Opera', Winton Dean describes this work as “a projection of the moral disintegration of the Roman people, suggested perhaps by the collapse of the Nazi regime in Germany. Everything is concentrated on creating an impression of growing chaos” (p. 155). Winton Dean, Dorothy Moore, and Phyllis Hartnoll's 'Catalogue of Music Works Based on the Plays and Poetry of Shakespeare' also lists the following, which I have annotated, though I've been unable to find any further information:

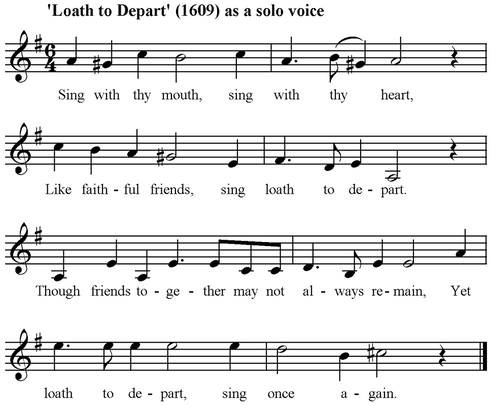

Curiously, several songs from the pop world relate to Shakespeare's play. Phish's 1994 'Julius' draws on Shakespeare's account, according to The Phish Companion: A Guide to the Band and Their Music. The American rock band The Ides of March (of 'Vehicle' fame) is a direct reference to Shakespeare, stemming from their bassist, Bob Bergland, who read Julius Caesar in high school. There are also several pop recordings based on the ancient Roman dictator that might or might not relate to Shakespeare's play: In his book Shakespeare: His Music and Song, A.H. Moncur-Sime writes of the Comedy of Errors, "This seems to be one of the very few plays in which music bears not the slightest part." (p. 99) And John H. Long, in his book Shakespeare's Use of Music, hypothesizes that the lack of music might have been "because there was no dramatic purpose to be served by music. He could have inserted an extraneous song or two, as was often done in the plays of the period, but he did not choose to do so." (p. 52) But while there are no specific songs in the script, there are four explicit musical references - and they do serve dramatic purposes. The first comes 2.2. Unbeknownst to him, Antipholus of Syrause (hereon abbreviated AofS) has been mistaken for his identical twin brother, Antipholus of Ephesus (AofE) by Adriana, AofE's wife. “The time was once, when thou unurg'd wouldst vow / That never words were music to thine ear … Unless I spake,” she admonishes who she thinks is her husband. “[H]ow comes it, / That thou art then estranged from thyself?” (113-14 & 119-20) The musical reference in this case emphasizes AofE's affection for his wife, and thus contributes to her sense of betrayal that her “husband” no longer seems to recognize her. The second occurrence is in 3.2. Not understanding the situation, AofS plays along (pretends to be Adriana's husband) until he spies Adriana's sister, Luciana, whereupon he falls in love with her. Once AofS and Luciana are alone together for the first time, he admits his romantic interest. “Your weeping sister is no wife of mine,” he says honestly, though Luciana doesn't believe him. “Nor to her bed no homage do I owe: / Far more, far more, to you do I decline.” (42-4) How curious that he says “decline” when “incline” is the more obvious word choice – he is inclined (motivated) to love Luciana over Adriana, not declined (politely refusing). But of course this is no error on Shakespeare's part: Decline in this instance might also mean “lay down” (ie: in a bed together). And if we instead define decline as “go down”, there might even be a whiff of cunnilingus in this linguistic choice. Anyway, Luciana, still thinking that AofS is AofE and thus her brother-in-law, is horrified by the suggestion that she would so betray her sister. But AofS persists. “[T]rain me not, sweet mermaid with thy note, / To drown me in thy sister's flood of tears”, he urges. “Sing, siren, for thyself, and I will dote” (45-7). Alluding to mermaid and siren singing symbolizes the extent of his ardor and stiffens his seduction. The third instance comes at the end of the same scene. AofS rendezvouses with his servant, Dromio of Syracusa (DofS), who is stuck in a similar situation: Though he's also unaware of the error, DofS has been mistaken for his identical brother, Dromio of Ephesus (DofE), by Nell, DofE's fiance. In comparing their situations, DofE and AofE both agree that the city is cursed, and so promptly plan their departure. But in doing so, he must abandon Luciana. Oh well, he thinks, “I'll stop mine ears against the mermaid's song.” (164) Where earlier in the scene AofS referred to Luciana as both a mermaid and a siren, now he only refers to her as a mermaid. This is because sirens' song is supposedly so beautiful that anybody who heard it couldn't resist it – that's why Odysseus famously incapacitated himself before approaching the sirens in The Odyssey. AofS's resolve to leave has overruled his lust, obviously Luciana does not have the sirens' power of persuasion. Fourth and finally, in act 4.3, DofS refers to a problematic law enforcement officer as “like a base-viol in a case of leather” (23). The viol is a Renaissance- and Baroque-era ancestor to the modern violin. The bass-viol is akin to the modern cello. But Shakespeare writes base – not bass. Like the decline vs. incline pun described above, this “typo” is not an accident – it contributes to our understanding of the scene. In this context, base means inferior quality, while leather symbolizes superior quality. So describing a public safety official as such illustrates how his shady behavior has been shielded through a veneer of legitimate authority. Apparently all cops were bastards even 400 years ago! There might or might not be additional, less obvious, musical references. Russ W. Duffin observes one potential connection in Shakespeare's Songbook, pointing out that four Shakespeare plays – including Errors – might allude to the Elizabethan song 'Loath to Depart' (p. 256).

Interestingly, Duffan also notes that 'Loath to Depart' is a four-part round, which in theory could continue ad infinitum, musically capturing the hesitancy to exit articulated by the title (p. 257).

In the opening scene of Errors, Egeon utters a phrase nearly identical to that song's title while describing his unfruitful search for his missing sons: Five summer have I spent in farthest Greece, Roaming clean through the bounds of Asia, And coasting homeward, came to Ephesus; Hopeless to find, yet loath to leave unsought Or that, or any place that harbors men. (132-6) It's hardly conclusive, but certainly a possibility that Shakespeare intended this connection. And even if he never intended it, the parallel is still present Though none of them have secured a spot in the standard repertoire, history contains several operas and musicals based on The Comedy of Errors. Among the better-known adaptations are Stephen Storace's 1786 opera buffa Gli Equivoci, Henry Bishop's 1819 opera The Comedy of Errors, and Richard Rodgers' and Lorenz Hart's 1938 musical The Boys From Syracuse. It appears that the main reason Storace's opera is still remembered today has less to do with its own merits than the fact that he was a pupil of Mozart, and the libretto was written by Lorenzo Da Ponte, who collaborated with Mozart on Don Giovanni, The Marriage of Figaro, and Cosi Fan Tutte – all of which have entered the standard rep. Bishop's opera is peculiar because its overture and 14 musical numbers draw from Shakespeare's writings (and one Marlowe poem – apparently Bishop falsely attributed it to Shakespeare), but has no apparent connection to The Comedy of Errors except for its title and character names (but not character actions):

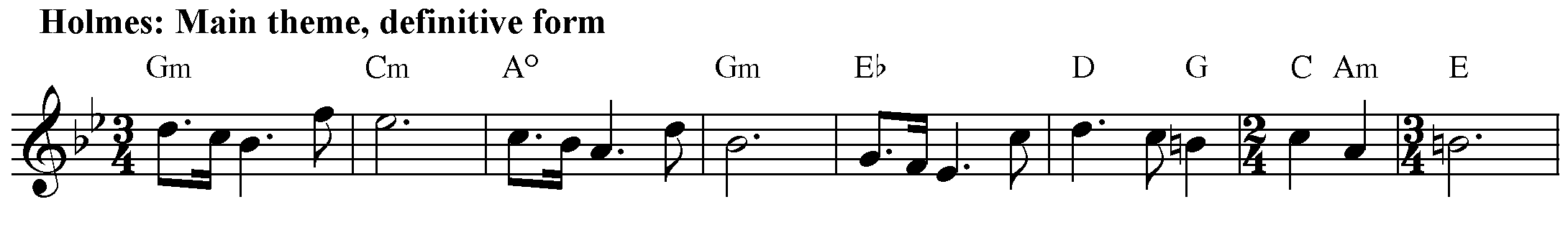

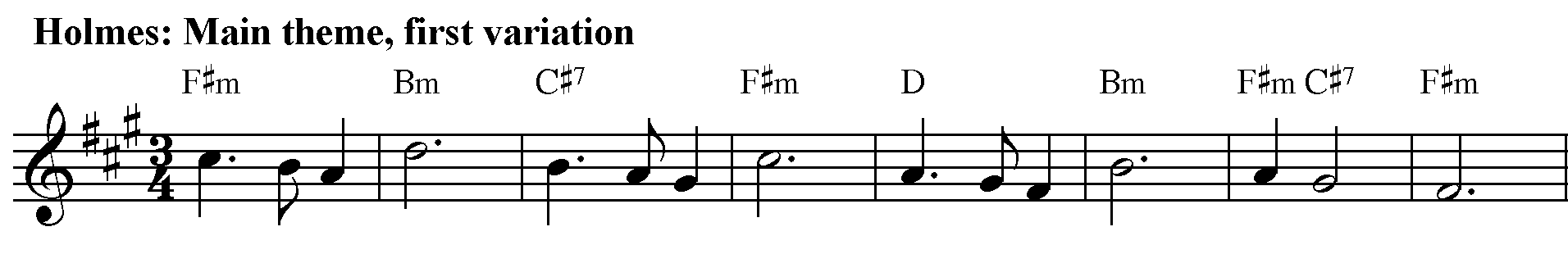

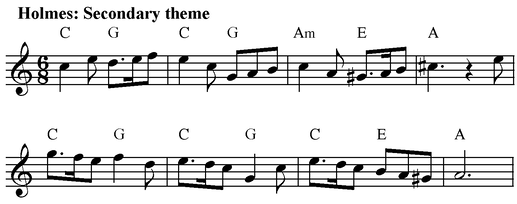

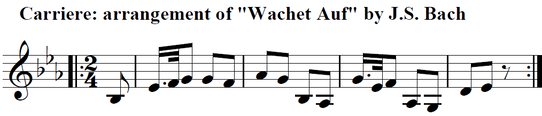

Third, Rodgers and Hart's The Boys From Syracuse is clearly based on The Comedy of Errors. Though it takes some significant departures from Shakespeare, it also adds some interesting symbolism absent from the original. As Irene Dash writes in Shakespeare and the American Musical, Hart's lyrics to 'Falling in Love with Love' features “love's blindness intrud[ing] on the romantic notion. … [L]ove makes us unable to see a lover clearly; we must struggle for hints of his reality” (p. 29): I fell in love with love one night When the moon was full I was unwise with eyes Unable to see I fell in love with love With love everlasting But love fell out with me Though Shakespeare explores the “love is blind” notion elsewhere (The Merchant of Venice: 2.6.36, A Midsummer Night's Dream: 1.1.234 & 5.1.4-22, Romeo and Juliet: 2.3.67-8, and Sonnet 148) he somewhat surprisingly does not pursue that idea in Errors, where it could nicely supplement the themes of romantic attachment and mistaken identity. Lastly, how have composers written music to accompany performances of The Comedy of Errors? Obviously, with covid19 quarantine in place, I can't attend any live performances. But, I discovered and watched two video recordings: The first was the BBC's 1983 production, directed by James Cellan Jones, with music by Richard Holmes; the other a 1989 performance by The Stratford Festival of Canada, directed by Richard Monette, with music by Berthold Carriere. Holmes' score employs two recurring themes. His main theme is heard only three times in its definitive form (at the very beginning, during the scene change from 4.4-5.1, and at the very end). However it resurfaces in disguise frequently. The first variation – clearly related in rhythm and harmony, though it has a completely different cadence – is heard between 1.2-2.1, and as intermission segues to 4.1. A second variation is heard as 3.1 transitions to 3.2. There's also a Rennaissnace-esque secondary theme that shares similarities in its cadences to the definitive version of the main theme. It is heard three times: From 2.1-2, as 3.2 segues to intermission, and from 4.3-4. Less creative, elaborate, and involved – but no less effective – than Holmes, Carriere's score is based on arrangements of J.S. Bach. While several of Bach's most famous melodies are heard throughout, a swung up-tempo rendition of the tune from his Cantata 140 “Wachet Auf” serves as the play's principal theme. Were I to compose music for Errors, I'd write a memorable main theme in two distinct tonalities – perhaps E major after Ephesus and E-flat major after Syracuse (S being German for E-flat) – to capture the whimsical nature of the story and its theme of mistaken identity. But I wouldn't try to do to much – the music would be limited to scene changes, and there'd be little underscoring. The danger of doing anything more sophisticated is that the play is already confusing enough – there's no reason to complicate further! I'd write snippets based on that main theme for each of the following:

The 472-mile drive took 11 hours and 36 minutes, including stops. On March 7, I arrived back home in Indianapolis following a brief but grueling lecture tour through Illinois and Missouri in which I delivered seven presentations in four days. To keep me company through the endless rural landscapes of Interstate 70, I downloaded Jillian Keenan's 2016 memoir SEX WITH SHAKESPEARE. I'm not entirely sure why I chose that title – I've never been a fan of Shakespeare (I can't say the same for sex!), but I've always felt like I should be. So, having only the slightest idea what Keenan's book was actually about, I hit play as I left Kansas City, and the 10-hour audiobook concluded just before pulling into my garage. In short, SEX WITH SHAKESPEARE is Keenan's realization that she's a spanking fetishist, and how Shakespeare assisted her self-acceptance. “If I could find myself reflected in Shakespeare's world,” she confides in the opening chapter, “maybe that meant I wasn't as unnatural as I feared.” (p. 21) Though I had difficulty relating to either subject, I found her story and writing engaging and moving. I liked it so much that I bought a hard copy. Four days later, covid19 hit home: Both Ball State and Butler canceled all remaining in-person classes, and quarantine began. Since March 12, I've barely left the house. The first several weeks were extremely stressful, as all the courses I was taking and teaching suddenly switched to online formats. After that chaos settled and I acclimated to the new normal, I knew I had to find something new to engage with intellectually. Taking and teaching classes is, of course, extremely intellectually challenging (that's why I enjoy it), but I needed something more – something I'd never done before. I'd never read Shakespeare outside of school. My freshman high school English class studied ROMEO AND JULIET (for which I composed my opus 1, a piano solo that I'm still rather proud of), my sophomore class covered MACBETH, and I scrutinized HAMLET last fall for a doctoral seminar – all three of which I struggled with, but ultimately enjoyed. And so, inspired by Keenan and those three plays, I bought a used copy of THE RIVERSIDE SHAKESPEARE on Amazon for $12 and embraced my new-found quarantine-induced free-time. It took 69 days (of course it did!) and about 400 hours (estimating an average of 5-6 hours per day) to read all 38 plays at least once (8 of them twice). As I finished each one, I awarded entirely subjective ratings out 10. Below is my ranking system and initial thoughts (a mix of summary, explanation, and criticism) on all 38. 1/10 – Few redeeming qualities (1 play) 2/10 – A few standout qualities (1 play) 3/10 – Significant problems (4 plays) 4/10 – Slightly more bad than good (3 plays) 5/10 – Equal parts good and bad (3 plays) 6/10 – Slightly more good than bad (5 plays) 7/10 – Good, but with problems (9 plays) 8/10 – Very good (5 plays) 9/10 – Excellent (4 plays) 10/10 – Extremely compelling (3 plays) 1/10 – Few redeeming qualities (1 play) TROILUS AND CRESSIDA This was the only play that tempted me to give up. I found the story and characters bland. That combined with its length (3,592 lines makes it Shakespeare's seventh-longest play) made TROILUS a slog! It was also one of the most challenging plays to understand and least rewarding – I put more effort into deciphering TROILUS than any other, yet got less out of that effort than any other. 2/10 – A few standout qualities (1 play) ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA Objectively, this isn't a terrible play; but subjectively, I couldn't stand it – I hate all the main characters! Antony is a hollow shell of a man, never able to balance what he wants with he needs, and incapable of long-term planning; Cleopatra is an ancient example of manic/depressive bipolar disorder and its problems when not properly managed; Caesar cares mostly about public image (a true politician); Lepidus is feeble and out-matched by every other character, even though he's the eldest and most experienced; Pompey craves power yet refrains when opportunity knocks, not out of moral outrage but out of concern for what people will think of him. Clearly that's all part of Shakespeare's plan – it is a tragedy, after all – but I don't find terrible decision-making engaging. 3/10 – Significant problems (4 plays) TWO NOBLE KINSMEN I quote from this play in my “Baseball Before the Civil War” presentation (it references stoolball, a predecessor to modern day baseball, in V.ii.74), so I was quite eager to read the entire play and thus have a better understanding of the larger context in which that quote appears. But I was disappointed: The characters and plot make no sense! The title characters are cousins Palamon and Arcite. Captured in battle and imprisoned together, they swear enduring allegiance and mutual affection. “[H]ere being thus together,” comments Arcite with more than a hint of homoeroticism, “We are one another's wife” (II.ii.78-80). “You have made me / (I thank you, cousin Arcite) almost wanton / With my captivity”, Palamon immediately reciprocates. “What misery / It is to live abroad” (95-8). All of that changes, however, as soon as they spot Emilia. Both are immediately smitten and start competing to win her hand, despite her lack of interest in either man. For some reason, “The cause I know not” (222), Arcite is released from prison and “Banish'd. … [N]ever more / Upon his oath and life, must he set foot / Upon this kingdom.” (244-6) But, still infatuated with Emilia, he remains, and enlists in a foot race and wrestling tournament (wha?), where he wins both (wha??), and thus wins Emilia's hand in marriage (wha???). Meanwhile, the jailer's daughter (she's never given a name) falls in love with Palamon (even though he despises her), and busts him out of prison (even though that means her father will be executed for failing to retain his prisoners) in the hope that he'll love her in return. Instead, he ignores her, and immediately pursues Emilia, unaware that she's now betrothed to Arcite. Eventually, the cousins reunite and agree to fight to the death (wha????), with the winner wedding Emilia (wha?????). As they joust, the local Duke enters. “Save their lives,” he orders in III.vi.251, “and banish 'em”, apparently forgetting that he had banished Arcite already, just one scene prior! Shortly thereafter, Palamon and Arcite resume their scuffle, and Arcite proves victorious. With Palamon about to be executed, news arrives that Arcite has been fatally wounded in horse accident (wha??????) and so Palamon can marry Emilia after all. In the midst of all that, a wooer (he is never given a name, either) pretends to be Palamon in order to trick the jailer's daughter into marrying him (wha??????????????????). Clear as mud, right? And that's why KINSMEN is so problematic – nothing makes any sense! I associate this play with TWO GENTLEMEN OF VERONA (see below), which also features two young men jockeying for the love of a single woman. But VERONA is the better play because the characters and situations actually make some sense (until the very end – but I'll address that later). KING JOHN and HENRY VI, PART ONE My favorite part about reading Shakespeare's history plays was that I knew basically nothing about English political history, so every bit of information was new and stimulated my curiosity. I watched a dozen or so documentaries as I read through those ten plays, which greatly enhanced my understanding of the historical events on which they are based. That being said, my least favorite part was the asinine decision-making of the characters – these people were all idiots! And that inanity is highlighted in KING JOHN and HENRY VI, PART ONE, both of which revolve around differing interpretations of the royal line of succession. It begs the question: Why didn't somebody determine the rules of succession beforehand?! KING JOHN is most significant in the context of Shakespeare's other histories. It has little merit on its own, rather like how the STAR WARS prequels relate to the original trilogy. Its most important lines come at its close, which issue a stern warning against English civil war: This England never did, nor never shall, Lie at the proud foot of a conqueror, But when it first did help to wound itself. ... Come the three corners of the world in arms, And we shall shock them. Nought shall make us rue, If England to itself do rest but true. (V.vii.112-8) That prophesy unfolds most clearly in HENRY VI, PART ONE. “[W]hat a scandal is it to our crown”, King Henry VI berates his underlings in III.i.69-73, “That two such noble peers as ye should jar! … Civil dissension is a viperous worm / That gnaws the bowels of the commonwealth.” As foretold in JOHN, that civil disobedience has foreign ramifications as England loses control over France. HENRY VI, PART ONE might also be Shakespeare's least poetic play – the verse (or rather lack thereof) and imagery lacks depth and nuance (excepting IV.v). It's also not a terribly long play (2,931 lines), but it feels like it is given how little actually happens in it. THE WINTER'S TALE I know this is a favorite for many Shakespeare enthusiasts, but, like ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA, I find the characters (mostly Leontes) flat and obnoxious. Leontes' unfounded jealousy destroys his family and his kingdom, then he suddenly changes his mind when “Apollo's priest” tells him he's being an idiot (III.ii.127-36). “The heavens themselves / Do strike at my injustice”, he claims out of nowhere in III.ii.146-7 & 153-5. “Apollo, pardon / My great profaneness 'gainst thine oracle! I'll reconcile me”. Redemption is one of the most difficult character arcs to execute well. A good example comes from STAR WARS: Darth Vader is redeemed at the end of RETURN OF THE JEDI. In that case, though, Vader's redemption doesn't come out of nowhere (like Leontes'), but rather is the result of carefully planted seeds in the previous films that set up this transformation. Such seeds are nowhere to be found in THE WINTER'S TALE, thus Leontes' redemption is undeserved on the part of the character and clumsy on the part of the author. 4/10 – Slightly more bad than good (3 plays) ALL'S WELL THAT ENDS WELL If Leontes in THE WINTER'S TALE is the worst example in Shakespeare of unearned redemption, then Bertram in ALL'S WELL is the second-worst offender. He's forced to marry Helena (who genuinely loves him) at the start, even though he can't stand her. The middle of the play continuously establishes him as a terrible person, and then in the last few lines he suddenly repents. This transformation is not earned – it only happens as a way to end the story happily. That leads to the second major problem: If TWO GENTLEMEN OF VERONA (see below) exhibits the most egregious example of “tie it up in a bow” syndrome, then ALL'S WELL is the second-worst offender. The drama wraps up so abruptly, that it's almost like Shakespeare said, “Iunno how to end this, so I'll just throw in a happily-ever-after conclusion, and call it ALL'S WELL THAT ENDS WELL!” TWELFTH NIGHT Everybody loves this one, but I find it convoluted and tedious. Some of Shakespeare's plays read as if they took no effort at all to write – as if a complete and perfect idea flashed through his brain in a moment of profound inspiration, and all he had to do was write it down without changing a word. TWELFTH NIGHT is the opposite of that – I imagine Shakespeare had a brilliant but preliminary idea, then struggled to find a way to make that idea make sense, contorting this and tweaking that until he ended up with product that sort of makes sense, but not really. On the other hand, the strong theme of gender-bending (even more so than in other Shakespeare plays) makes this a much more interesting work in the 21st century than it could have been in the early 17th, even though women were legally barred from performing on stage at that time. Obviously, contemporary productions have much more freedom to play with these undercurrents of homoeroticism than actors had in Shakespeare's day. THE MERCHANT OF VENICE I will forever associate THE MERCHANT OF VENICE and TWELFTH NIGHT – both are highly regarded works that I struggle to enjoy. The horrors of the Holocaust inevitably give this play (which centers on the Jewish character Shylock) a different tone than it had in Elizabethan England (when practicing Judaism was illegal). It seems to me that Shakespeare never intended his audience to sympathize with Shylock, but instead view him as a laughingstock as he endures one devastating loss and humiliation after another. A more modern and empathetic interpretation makes Shylock sympathetic. Thus, like TWELFTH NIGHT, VENICE is also a play that has much more to offer in contemporary interpretation and production than it would've had when it was written. 5/10 – Equal parts good and bad (3 plays) CORIOLANUS Rather similar to Richard Wagner's opera RIENZI, CORIOLANUS tells the story of a valiant Roman soldier who, falsely accused by Rome's citizens and thus banished from the city, teams up with Rome's enemy, the Volscians, to destroy Rome in revenge. But after a visit and pleas from his wife and young son, Coriolanus cancels the attack. That ticks off the Volscians, who plan to kill Coriolanus for abandoning them, but the fickle Roman public beat them to it, killing the title character in the final scene for some reason that either I missed or is not clearly explained. It's really not a bad play, but it's really not good, either. But it does address several topics that remain relevant: wealth and its uneven distribution throughout society, and the capricious nature of public opinion. As a side note, it also includes some of Shakespeare's best insults in II.i: