|

The album we now know as Abbey Road was originally titled Everest - not after the mountain but after the brand of cigarettes smoked by the Beatles' recording engineer Geoff Emerick. Regardless, the band considered flying to Tibet to shoot the cover photo, but eventually opted to simply call the album Abbey Road and shoot the cover photo on the crosswalk outside the studio. Nevertheless, on some level the band was thinking of the album as their pinnacle - and indeed (though this is subject to debate) the level of artistic sophistication and achievement surpassed anything the band accomplished up to that point, and represents a level that none of the four would ever reach again in their solo careers.

0 Comments

Formal structure in [44b] "Kansas City/Hey Hey Hey Hey"

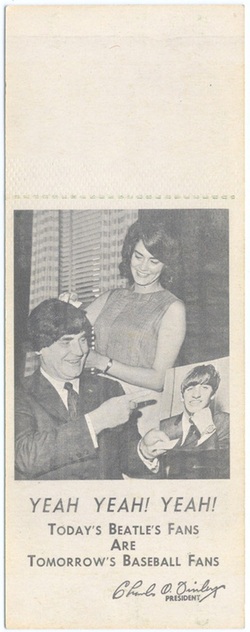

Intro (ind) 0:00-0:08 Verse 1 0:08-0:29 Verse 2 0:29-0:51 Solo 0:51-1:13 Chorus #1 1:13-1:35 Chorus #1 1:35-1:57 Chorus #2 1:57-2:19 Chorus #2/Coda 2:19-2:37* Comments: This one is unique in that it combines two completely different songs: "Kansas City", written by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller in 1952; and "Hey Hey Hey Hey" written by Richard Penniman (a.k.a. Little Richard), who liked to combine it with the Leiber/Stoller song in live performances to create a medley. The Beatles, who heard "Kansas City/Hey Hey Hey Hey" on the B side of Little Richard's single "Good Golly Miss Molly" (released 1958), adopted the medley for their own by 1962, dropped it from their set list in 1963, and then revived the song in preparation for a performance in Kansas City on September 17, 1964. Perhaps out of need for additional songs rather than artistic merit, the medley was recorded and added to the album Beatles for Sale, released 1964. Point is that from a structural point of view, it's rather difficult to analyze precisely because it's actually two songs stuck together. Though it's clearly open to debate, for the sake of simplicity I have analyzed the "Hey Hey Hey Hey" section as two choruses (they share nearly identical chord progressions and durations - it's only the lyrics that differ) each with a repeat. The very last section fades to nothing, making it both an iteration of the second chorus and a coda.  In preparation for my LifeLearn Baseball course (debuting Spring 2013), I have been reading Charlie Finley: The Outrageous Story of Baseball's Super Showman by G. Michael Green and Roger D. Launius. I was aware, of course, of the Beatles' performance in Kansas City during the fall of 1964 American Tour, and that this performance prompted the band to perform the song "Kansas City", which they later recorded and released on the album Beatles for Sale. In other words, I knew of the concert from the band's perspective. What I did not know was the story from the ball club's perspective. This blog, then, will fill that gap. In 1965, Municipal Stadium was home to the Kansas City Athletics, who moved from Philadelphia in 1955. (The current KC baseball team is the Royals, who played their inaugural season in 1969 as an expansion team following the Athletics' move to Oakland a year prior.) The Athletics' owner was Charles Oscar Finley, an irascible and controversial man who would between 1972-1974 lead his team (by then the Oakland Athletics) to three consecutive World Series titles. Though he always denied it, as early as 1961 (his first season as owner) Finley had plans to move the franchise. This naturally caused irreparable damage in the minds of KC baseball fans (especially after blatantly lying about it). In a rare effort to mend public relations, Finley hired the Beatles to perform at his stadium. On the back of each ticket was a photo of Finley wearing a Beatles wig, pictured right. The band played a 31-minute set on September 17, 1964 to an audience of 20,280. Municipal Stadium, however, held 34,165, and 28,000 tickets would have had to sell to break even. "Kansas City was the only concert venue on the tour that didn't sell out. Many potential concertgoers stayed way after the Kansas City Star and others urged a boycott of the concert as a way of showing displeasure with Finley. Finley promised to give all of his after-expenses profits to a local charity, Children's Mercy Hospital, but because the concert did not sell out, Finley actually lost money - possibly becoming the first Beatles concert promoter ever to do so" (Green, page 77). Finley, however, in an attempt to put as positive a spin on it as possible, insisted "I don't consider it any loss at all. The Beatles were brought here for the enjoyment of the children in this area and watching them last night they had complete enjoyment. I'm happy about that. Mercy Hospital benefited by $25,000. The hospital gained, and I had a great gain by seeing the children and the hospital gain" (Miles, page 171). Some, though, did make money on the Beatles' KC visit, "especially the two people who acquired the bedsheets from the Beatles hotel rooms, which they then cut into small squares to sell as souvenirs. They netted $159,000 for their efforts" (Green, page 77) after purchasing the 16 sheets and 8 pillowcases for just $750 (Miles, page 171). Die hard Beatles fans may recall a similar incident in Robert Zemeckis' 1978 film I Wanna Hold Your Hand. Citations Green, Michael G. and Roger D. Launius. Charlie Finley: The Outrageous Story of Baseball's Super Showman. Walker & Company, New York, NY, 2010. Miles, Barry. The Beatles Diary, Volume 1: The Beatle Years. Omnibus Press, A Division of Book Sales Limited, New York, NY, 2001. Formal structure of [44] "She's a Woman"

Intro (verse) 0:00-0:11 Verse 1 0:11-0:43 Verse 2 0:43-1:15 Chorus 1:15-1:21 Verse 3 1:21-1:53 Solo 1:53-2:10 Chorus 2:10-2:15 Verse 4 2:15-2:47 Coda (verse, coda) 2:47-3:02* Comments: Coda features backing music of verse, with the title lyrics sung to new music. In the film A Hard Day's Night, at the very beginning, is a scene in which John Lennon, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr are being chased by a mob of screaming girls. Paul McCartney, however, avoided the problem by wearing fake facial hair, thereby disguising his identity and saving himself the trouble of dealing with the hysteria. The tactic was not created for the film - Paul actually used the trick on a regular basis. It had a liberating effect, allowing him to walk around in public without the debilitating insanity of Beatlemania. For those few hours, it was as if he was someone other than Paul McCartney.

Indeed, the disguise worked so well that the bassist wondered if the same stunt could be employed by the whole band. Just as it did with Paul, assuming different identities could free the band to try different things by allowing the group to get outside of themselves. Quoting Paul: "With our alter egos we could do a bit of B. B. King, a bit of Stockhausen, a bit of Albert Ayler, a bit of Ravi Shankar, a bit of Pet Sounds, a bit of the Doors; it didn't matter, there was no pigeon-holing like there had been before" (Miles, page 306). After a crazy year in 1966 - in which they stopped touring due in large part to the delirium of live performances - the band found the notion quite appealing, and decided that for their next album they would not be the Beatles. Citations Miles, Barry. Paul McCartney: Many Years From Now. Henry Holt and Company, New York, NY, 1997. Formal structure of [43] "Eight Days a Week"

Intro (ind, coda) 0:00-0:07* Verse 1 0:07-0:35* Verse 2 0:35-1:02 Middle 8 1:02-1:16 Verse 3 1:16-1:44 Middle 8 1:44-1:58 Verse 4 1:58-2:25 Coda (verse, intro) 2:25-2:42* Comments: First song (not just first Beatles song) to feature a fade-in intro. Another four-part verse structure in which the third part contrasts the other three parts (just like [31] "A Hard Day's Night", [35] "Things We Said Today", [40] "I Don't Want to Spoil the Party", and [42] "No Reply"): Ooo I need your love babe, guess you know it's true Hope you need my love babe, just like I need you Hold me, love me, hold me, love me I ain't got nothing but love babe, eight days a week. Verses 1 and 3 share identical lyrics, as do verse 2 and 4. Interestingly, vocal harmony is added in this contrasting third verse subsection, but only on verses 2 and 4 - not on verses 1 and 3. 2-part coda: first part based on repetition of the title lyrics (which comes from the end of the verse); second part similar to the introduction but independent from the rest of the song. The basic formula of a 12 bar blues progression, as written in Roman numerals with each character representing one measure, is as follows:

I I I I IV IV I I V IV I I This pattern can, of course, be used in any key. Below are 5 examples in C major: in D major: in E major: in G major: in A major: C C C C D D D D E E E E G G G G A A A A F F C C G G D D A A E E C C G G D D A A G F C C A G D D B A E E D C G G E D A A 27 songs recorded and released by the Beatles use a 12 bar blues progression or something comparable. Of those 27, 15 were original compositions and 12 were covers. Below are all 28 tracks, listing their year of release, tonality, a concise harmonic analysis, and brief commentary. [9c] "Boys" (1963) E major E7 E7 E7 E7 A7 A7 E7 E7 B7 A7 E7 B7 It is clearly modeled on the 12 bar blues - the only alterations being (a) every chord is a seventh chord (making each chord slightly more dissonant and gritty sounding), and (b) the very last chord is B (the dominant in E major) instead of the traditional E. No doubt this is because B7 leads very nicely to E, which starts the progression all over again. [9d] "Chains" (1963) Bb major Bb Bb Bb Bb Eb9 Eb9 Bb Bb F9 Eb9 Bb F Another clearly modeled on the 12 bar blues. The only alterations are (a) a few ninths are added to a few chords, and (b) the very last chord is F (the dominant in Bb), which of course leads strongly back to Bb to start the progression all over again. [13c] "Money (That's What I Want)" (1963) E major E7 E7 (A) E7 E7 A7 A7 E7 E7 B7 A7 E7 B7 In addition to adding sevenths to every chord, "Money" also adds an extra A chord in the second measure of each verse. This chord is listed in parentheses above because unlike every other chord listed above it does not represent a full measure. (If it did, it would make this a 13 bar blues pattern instead of 12.) Rather, it represents a brief instrumental fill (listen right after the words "life are free") that embellishes the 12 bar blues progression but does not interfere in any way with its function. [14b] "Roll Over Beethoven" (1963) D major D7 G7 D7 D7 G7 G7 D7 D7 G7 A7 D7 D7 In addition to adding sevenths to every chord, "Roll Over Beethoven" also replaces the second chord (which 'should' be D7) with a G7. The 9th and 10th bars are also reversed (G7 A7 instead of A7 G7). [17] "Little Child" (1963) E major E7 E7 E7 (A) E7 B7 A F#7 (B7) E The most significant departure from the mold that is still clearly based on the mold, "Little Child" turns the 12 bar blues into an 8 bar blues for the verses. It omits measures 4-8 and replaces them with 9-12. But those measures offer something new as well when an F#7 (which has no place in a normal 12 bar blues) is used in the 11th measure. The solo section, however, adopts a more usual 12 bar pattern . . . E7 E7 E7 E7 A A E7 E7 B7 A F#7 B7 . . . although it still is hardly standard with the added F#7 in the 11th measure and yet another dominant chord in the 12th. [23] "Can't Buy Me Love" (1964) C major C7 C7 C7 C7 F7 F7 C7 C7 G7 F7 F7 C7 The only substantial deviation from the model is using an F chord in bar 11 (instead of the more typical C). [24] "You Can't Do That" (1964) G major G7 G7 G7 G7 C7 C7 G7 G7 D7 C7 G7 D7 Just like [9c] "Boys", [9d] "Chains", [13c] "Money (That's What I Want)", and [17] "Little Child", "You Can't Do That" uses a typical 12 bar blues progression except for the very last chord, which is changed to a dominant to heighten the harmonic tension and release when the pattern is repeated. [29b] "Long Tall Sally" (1964) G major G G G G C C G G D7 C7 G D7 The comments above regarding [24] "You Can't Do That" may be iterated in regards to [29b] "Long Tall Sally". [31b] "Matchbox" (1964) A major A7 A7 A7 A7 D7 D7 A7 A7 A7 E7 A7 E7 The only significant deviations from the mold are the 9th through 12th bars (A7 E7 A7 E7 - again ending with a dominant chord - instead of the more typical E D A A). [32b] "Slow Down" (1964) C major C C C C C C C C F F F F C C C C G F C C C C C C "Slow Down" takes the 12 bar blues and augments it into a 24 bar blues. The first 16 measures of "Slow Down" are simply the first 8 measures of a normal 12 bar blues doubled (but proportionally maintained); and the last 8 measures of "Slow Down" are just the last 4 measures of normal 12 bar blues with 4 extra bars of C grafted on to the end. [44] "She's a Woman" (1964) A major A7 D7 A7 A7 A7 D7 A7 A7 D7 D7 D7 D7 A7 D7 A7 A7 E7 E7 D7 D7 A7 D7 A7 E7 Just like [32b] "Slow Down", "She's a Woman" takes the 12 bar blues progression and doubles it into a 24 bar progression. The D7 chords in measures 2, 6, 14, and 22 serve as harmonic ornamental embellishments and thus do not interfere with the overall function of the 12 (24) bar blues progression. (Since this is a McCartney original, perhaps Paul learned the trick from Berry Gordy Junior and Janie Bradford, who wrote [13c] "Money (That's What I Want)" or from Chuck Berry, who wrote [14b] "Roll Over Beethoven".) This is in contrast to the use of the same chord when it is heard in measures 9-12 and 19-20, which do function as integral components of the blues progression. "She's a Woman" also employs a dominant in the final measure (just like [9c] "Boys", [9d] "Chains", [13c] "Money (That's What I Want)", [17] "Little Child", [24] "You Can't Do That", [29b] "Long Tall Sally", and [31b] "Matchbox") [44b] "Kansas City/Hey Hey Hey Hey" (1964 in UK, 1965 in US) G major G G G G7 C C G G D C G G (D) This one is about as standard as a progression can get. The only two things I can mention are the use of a seventh in the 4th bar (to heighten the pull towards C in the 5th bar), and once again the band uses a dominant chord (in this case D) in the final bar (although this time only for the second half of that final bar) to heighten the pull towards the beginning of a repetition of the progression. [46b] "Everybody's Trying to Be My Baby" (1964) E major E E E E A A E E B7 A E E This one, too, is about as standard as a progression can get. The only thing I can mention is the use of a seventh in the 9th bar, which provides more harmonic dissonance and thus tension to the chords. [46c] "Rock and Roll Music" (1964) A major A7 A7 A7 A7 D7 D7 A7 A7 E7 E7 E7 A7 E7 A7 "Rock and Roll Music" extends the 12 bar blues to a 14 bar blues by repeating the last two measures. [56b] "Dizzy Miss Lizzy" (1965) A major A A A A D D A A E7 D A E7 The only non-standard thing about this one is the use of a dominant chord in the final bar (non-standard, that is, for those other than the Beatles - this is now the 10th of 15 Beatles tracks that use the 12 bar blues to do so, making the deviation actually more common than the standard). [56c] "Bad Boy" (1965 in US, 1966 in UK) C major C7 C7 C7 C7 C7 C7 C7 C7 F7 F7 F7 F7 C7 C7 C7 C7 G7 F7 C7 G7 "Bad Boy" pulls the same trick found in [32b] "Slow Down" and [44] "She's a Woman" in that the first 8 bars of the 12 bar blues have been doubled in length, but retain their proportions. Unlike "Slow Down" and "She's a Woman", however, the final 4 bars of "Bad Boy" are not augmented. This makes a unique (at least in the Beatles' recorded and released output up to this point in history) 20 bar blues progression. The final chord, once again, is a dominant. [58] "I'm Down" (1965) G major G G G G C C G G C C D7 G D7 G Perhaps following the example of [46c] "Rock and Roll Music", "I'm Down" turns the 12 bar blues into a 14 bar blues by repeating the final two measures of the pattern. [65] "Day Tripper" (1965) E major E7 E7 E7 E7 A7 A7 E7 E7 F#7 F#7 F#7 F#7 A7 G#7 C#7 B7 "Day Tripper" is a prime example of what I have come to call the Beatles' adolescence (roughly November of 1964 through December of 1965) - a period of just over one year in which their output is split between songs with clear roots in the past ("Everybody's Trying to be my Baby", Dizzy Miss Lizzy", "Run for your Life", et cetera) and songs that begin to push the boundaries and anticipate the band's experimentation and artistic breakthroughs of the later 60's ("You've Got to Hide Your Love Away", "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)", "In My Life", et cetera). It is as if the band has one foot still firmly in the teeny bopper pop music world and simultaneously the other foot in the more grown-up 'art music' world, just as an adolescent retains aspects from childhood while simultaneously growing into adult life. This can be observed in analyzing "Day Tripper": The first eight measures are identical to the 12 bar blues model (representing the retrospective side), but then the pattern is broken and new and unusual chords - totally and completely unrelated to the 12 bar blues model - are heard (representing the anticipatory, progressive side). Neither F#7 nor G#7 'belong' in E major - much less in an E major 12 bar blues - and yet a listener intuitively feels their propriety. The Beatles are finding their own unique individual solutions to musical problems. They are beginning to distance themselves from the past, taking one of their first steps towards full artistic maturity. "Day Tripper" is one of the first hints at the innovations to come. [74] "The Word" (1965) D major D7 D7 D7 D7 G7 G7 D7 D7 A G D7 D7 This one's about as standard as it can get. [118] "Flying" (1967) C major C C C C F7 F7 C C G7 F C C Fits the mold perfectly. [126] "Don't Pass Me By" (1968) C major C C F F C C G G F F C C Uses the same chords as the mold, in the same order, over the same duration, but with different proportions. [139] "Yer Blues" (1968) E major E E A7 E G,B7 E,A,E,B7 Where [56c] "Bad Boy", [32b] "Slow Down", and [44] "She's a Woman" maintained the proportions of the 12 bar blues but doubled its length (24 instead of 12), "Yer Blues" likewise maintains the proportions but halves its length (6 instead of 12). The last two bars both use more than one chord. The last chord is once again a dominant. [146] "Birthday" (1968) A major A7 A7 A7 A7 D7 D7 A7 A7 E7 E7 A7 A7 The only difference between this and the template is the 10th chord (which is E when it 'should' be D). [155] "Why Don't We Do It In The Road" (1968) D major D7 D7 D7 D7 G7 G7 D7 D7 A7 G7 D7 D7 Standard. [163] "For You Blue" (1970) D major D7 G7 D7 D7 G7 G7 D7 D7 A7 G7 D7 A7 The second chord is a G (instead of D), but this is ornamental and does not effect the function of the 12 bar blues pattern ( a la [13c] "Money (That's What I Want)", [14b] "Roll Over Beethoven", and [44] "She's a Woman"). Last chord is once again a dominant. [166] "The One After 909" (1970) B major B7 B7 B7 B7 B7 B7 B7 B7 B7 B7 E7 E7 B7 F#7 B7 B7 Uses the same chords as a 12 bar blues and nearly in the same order, but it's stretched to 16 bars in duration and is missing an E before the final B. The proportions are not the same as the model. This one does not use a dominant as a final chord. [168] "The Ballad of John and Yoko" (1969) E major E E E E E7 E7 E7 E7 A A E E B7 B7 E E Just like "909", "The Ballad of John and Yoko" stretches the 12 bar blues into a 16 bar blues by doubling the first four measures. It uses the same three chords in nearly the same order (it's missing an A before the final E). CONCLUSIONS

1964: 9 1965: 6 1966: 0 1967: 1 1968: 4 1969: 1 1970: 2

Formal structure of [42] "No Reply"

Verse 1 0:00-0:33 Verse 2 0:33-1:03 Middle 8 1:03-1:34 Verse 3 1:34-2:05 Coda 2:05-2:15 Comments: Similar to [31] "A Hard Day's Night", [35] "Things We Said Today", [40] "I Don't Want to Spoil the Party", the verse structure of "No Reply" can be divided into four parts: This happened once before, when I came to your door, no reply. They said it wasn't you, but I saw you peep through your window. I saw the light, I saw the light. I know that you saw me, 'cause I looked up to see your face. The first, second, and fourth of these subsections are essentially musically identical (the same chords, same character, roughly the same melody), but the third part is different (different chords, different character, very different melody, plus the addition of vocal harmonies and huge cymbal hits both noticeably absent from the other three subsections). No intro. Coda is the only time you hear the title lyrics, and is musically (but not lyrically) based on the third part of the verse. The Beatles played a great many songs using the 12 bar blues chord progression, especially during their early years (i.e. Hamburg and before). One reason for this was because 12 bar blues are very, very easy to play - it is often one of the first things a beginning guitar student will learn how to play. Since the band needed material and hadn't yet developed and honed their performance skills, the 12 bar blues was a natural fit.

Furthermore, the Beatles' early bass player was not Paul McCartney but Stuart Sutcliffe, who by all accounts was the least talented performer of the band. Stu's lack of ability as a performer limited the band's repertoire. Howie Casey, saxophonist with the band Derry and the Seniors with whom Stuart played in Hamburg, said of the bassist, "All we could do with Stu was to play twelve-bar blues. He couldn’t venture out of that" (Sutcliffe page 88). If the Seniors couldn't play anything but 12 bar blues because of Stu's limited facility on bass, no doubt the Beatles couldn't either. Even when Sutcliffe left the band and McCartney (a much more gifted musician) assumed the role of bassist, the Beatles' retained many 12 bar blues tunes in their repertoire, several of which wound up on Beatles records. As the band progressed and their musical abilities developed, however, their reliance on the formula decreased, replaced by their own unusual and strikingly original harmonic progressions. Certainly by 1967 the 12 bar blues was ancient history from the band' perspective. Referring to the orchestral passages in "A Day in the Life", Paul McCartney said, "It was very exciting to be doing that instead of twelve-bar blues" (Anthology page 247). (Odd that Paul would say that regarding 1967 when the previous year the Beatles released no songs whatsoever that incorporate the 12 bar blues.) During the three years from 1963 through 1965, the Beatles released 19 songs using the 12 bar blues or something comparable; during the five years from 1966 through 1970, only 8. CITATIONS Beatles. The Beatles Anthology. Chronicle Books, San Francisco, CA, 2000. Sutcliffe, Pauline and Douglas Thompson. The Beatles’ Shadow: Stuart Sutcliffe & His Lonely Hearts Club. Pan Books, an imprint of Pan Macmillan Ltd, London, UK, 2002. Formal structure of [41] "What You're Doing"

Intro (ind., verse) 0:00-0:14* Verse 1 0:14-0:31 Verse 2 0:31-0:46 Middle 8 0:46-1:01 Verse 3 1:01-1:18 Solo 1:18-1:32 Middle 8 1:32-1:48 Verse 4 1:48-2:00 Coda (verse) 2:00-2:30* Comments: Another two-part introduction. The first part of this intro is the closest thing to a drum solo on a Beatles track until [180] "The End" from Abbey Road. This drum pattern is not featured anywhere else in the song except for the coda. The coda is more developed than most, incorporating an extension of the fourth verse with two additional iterations of the lyrics "what you're doing to me" (2:00-2:08), the guitar lick from the intro and verse (2:08-2:12), a reprise of the drum break from intro (2:12-2:19), and finally the same guitar lick with backing from verse which fades out (2:19-2:30). |

Beatles BlogThis blog is a workshop for developing my analyses of The Beatles' music. Categories

All

Archives

May 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed