|

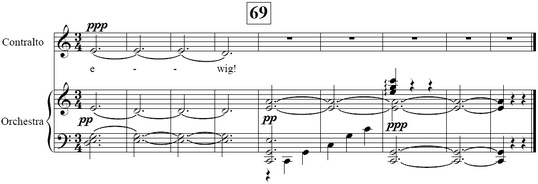

On 27 December 1963, The [London] Times published a now-famous article titled "What Songs the Beatles Sang", with the byline "From our music critic", presumed to William Mann. In his article (the full text of which may found here), Mann wrote, "one gets the impression that they think simultaneously of harmony and melody, so firmly are the major tonic sevenths and ninths built into their tunes, and the flat submediant key switches, so natural is the Aeolian cadence at the end of Not A Second Time (the chord progression which ends Mahler's Song of the Earth)." As a well-educated musician, I am both intrigued and confused by Mann's words. While I know what the terms "aeolian" and "cadence" mean separately, I have never previously encountered them used together. In his book A Hard Day's Write: The Stories Behind Every Beatles Song, Steve Turner is equally perplexed: "An 'aeolian cadence' is not a recognised musical description and generations of music critics have puzzled over exactly what Mann was referring to" (page 40). A quick Google search of the term "aeolian cadence" produces two basic types of results: first, those quoting Mann's article; second, those asking what Mann's article means. (Try it and you'll see.) This blog, then, will weigh the evidence in an attempt to discover precisely what he meant. The term "aeolian" refers to a specific type of scale consisting of the following interval pattern: W H W W H W W (where W = whole step, H= half step). This is the same pattern as the natural minor scale, and may also be described as the notes A to A on the piano if you play only the white keys. The term "cadence" refers to a concluding musical gesture, and cadences are usually found at the end of structural sections, or at the end of a song. Quoting a very popular and widely-used harmony textbook, "We use the term cadence to mean a harmonic goal, specifically the chords used at the goal" (Kostka/Payne, page 152). If the goal is reached at the end of a song, there is no reason to conclude by fade out. On the other hand, that sense of harmonic conclusion may be obfuscated by a fade out instead of a cadence. Though I suppose it is possible for a song to use both a concluding cadence and a fade out, I do not believe I have ever heard a song that actually does so. It would, after all, be redundant since both cadences and fade outs are concluding gestures. "Not a Second Time", however, is in G major (not aeolian) and uses a fade out instead of a cadence for its conclusion; so what exactly Mann was referring to by "Aeolian cadence at the end of Not A Second Time" is uncertain. My best guess is that the last several seconds of the song feature just two chords: G major and E minor, and the G major scale (G-A-B-C-D-E-F#-G) and the E aeolian (from which the chord E minor can be extracted) scale (E-F#-G-A-B-C-D-E) share identical notes, they just start on different pitches, making these two tonalities very closely related. I wonder if Mann heard this progression and mistakenly identified it as a cadence. Some scholars have concluded otherwise, suggesting Mann was referring instead to the E minor chords that follow D7 chords at the end of the Middle 8s: Am Bm D7 Em You hurt me then, You're back again. No, no, no, not a second time. Personally, I find this explanation less satisfying than the one above because (1) it's not "at the end" of the song, as the article specifies (though perhaps the article meant "at the end of the Middle 8"?); and (2) this pattern is known - as it was in 1963 - as a deceptive cadence, in which the fifth scale degree (in this case D7) resolves not to the first scale degree (G) as a listener might expect, but rather to the sixth (E minor). But Dominic Pedler, in his book The Songwriting Secrets of the Beatles, addresses that concern head-on: "Mann would argue that it is not the same thing as a "V-vi" Interrupted or Deceptive cadence because - at that precise point in the song - the role of the E minor as a "vi" is being questioned and is veering towards tonic status" (page 137). Yet this is uncertain: Typically a B7 would be needed to justify E minor as "tonic status", and the chord used in the song is a Bm - not a B7. This subtle but significant difference implies that E minor is not tonic, and thus this progression is a deceptive cadence. Or maybe that's precisely why Mann referred to this as an aeolian cadence and not a deceptive cadence - because if the song is in E aeolian, B would be minor (since D is natural, not sharp). Basically it comes down to opinion: How do you hear this passage - with G as tonic, or with E as tonic? Am Bm D7 Em You hurt me then, You're back again. No, no, no, not a second time. G major: ii iii V7 vi E aeolian: iv v bVII7 i Both are unusual, and evidence can be presented in favor of both, but I have to say I hear G as tonic, making this a deceptive cadence - particularly when looking on a slightly larger scale. Here are the lyrics and chords immediately preceding the passage in question: Am7 Bm7 G Em You're giving me the same old line. I'm wondering why. In this instance, G is quite clearly tonic. This firm tonal grounding and the use of very similar chords immediately following lends credence to calling the original progression a deceptive cadence and not an aeolian cadence. Another option: Perhaps Mann simply got his vocab terms confused and really meant "deceptive cadence" when he wrote "aeolian cadence". While this interpretation solves the problem of a lack of cadence, the issue over "at the end" remains. At the end... of what? If it's the end of the Middle 8, then problem solved; but if it's at the end of the song, we are still left with uncertainty. Mann provides another clue when he claims that the same chord progression concludes Gustav Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth), but simple observation proves otherwise. Below is a reduction of the last 10 measures of Das Lied (click to enlarge in a new window). This example shows a C9 chord (though the root is absent from these measures, it is heard shortly beforehand and a listener would have no problem retaining that tonality in their mind's ear) resolving to a C6 chord at marker 69. That C6 chord is the harmony that concludes the piece. By contrast, "Not a Second Time" concludes by fading out over alternating G and Em chords. While not entirely unrelated (both make use of the sixth scale degree), the degree of relation is far removed. Thus, the claim that "Not a Second Time" and Das Lied end with the same progression is irrefutably false. It would, in fact, be far more accurate to compare the ending of the Mahler to the ending of "She Loves You" (which was released four months prior to Mann's article) , which also ends with an added sixth chord. However, Mann has clearly shown that the word "end" is open to great interpretation. If, as was suggested early, Mann meant to refer to the cadence "at the end [of the middle 8]", then perhaps his use of the term "end" is similarly flexible regarding the Mahler: Perhaps the cadence is in the final movement of Das Lied, not at the very end but perhaps at the end of a particular section; yet listening to the entire 6th movement of Das Lied yields no such cadence. In fact, much of Mahler's later work (such as Das Lied and the 9th and 10th Symphonies) "follows Wagner's lead in taking tonality closer and closer to the breaking point. Nearly every piece of music before Wagner's time was very clearly in a particular key; Mahler's music, on the other hand, has long stretches that don't seem to be in a key at all" (Pogue, page 61). Cadences are largely dependent on tonality, and without tonality, the impact and effect of cadences are greatly thwarted. Nevertheless, Mahler scholar Constantin Floros found what he believed to be deceptive cadences at rehearsal marker 24-26 of the final movement of Das Lied in his book Gustav Mahler: The Symphonies (page 267-68), illustrated as a piano reduction below (click to enlarge): Personally, I don't hear these as cadences. Modulations, certainly, but the tonal expectation that characterizes cadences (and especially deceptive cadences) is greatly lacking in this excerpt - to the point where I cannot justify the label of cadence of any kind, much less deceptive cadence.

Even if these were explicitly clear deceptive cadences, they are not very similar to the progression in "Not a Second Time". In each of the three potential cadences in the Mahler, the bass ascends by half step (B-flat to C-flat, G to A-flat, and F to F-sharp), while the Beatles' cadence ascends by whole step (D to E). (Parenthetically, Mahler did use deceptive cadences in his 4th and 5th Symphonies. Maybe Mann was confused and meant to say one of those works instead of Das Lied? That might be too much of a stretch - even for William Mann.) After all of that, I think it's safe to say that regardless of what William Mann really meant, he failed to clearly express his ideas. Even so, Mann's article remains widely cited and quoted because even though Mann's analysis is faulty, it is the first instance of Beatles music being seriously analyzed. Quoted from 1972 in The Beatles Anthology, John Lennon (the song's primary author) said, "I still don't know what it means at the end, but it made us acceptable to the intellectuals. It worked and we were flattered." (page 96). Even so, Lennon could not help but make fun of the article, admitting a "quiet giggle when straight-faced critics start feeding all sorts of hidden meanings into the stuff we write. William Mann wrote the intellectual article about the Beatles. He uses a whole lot of musical terminology and he's a twit" (Anthology, page 96); and in a 1980 interview with David Sheff of Playboy, Lennon (despite mistakenly remembering the article referring to "It Won't Be Long") claimed, "To this day I don't have any idea what [aeolian cadences] are. They sound like exotic birds" (page 87). CITATIONS Beatles. The Beatles Anthology. Chronicle Books, 2000. Floros, Constantin. Gustav Mahler: The Symphonies. Amadeus Press, Portland OR, 1993. Kostka, Stefan and Dorothy Payne. Tonal Harmony. McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1995. Pedler, Dominic. The Songwriting Secrets of the Beatles. Omnibus Press, 2001. Pogue, David and Scott Speck. Classical Music for Dummies. IDG Books Worldwide, Chicago, IL, 1997. Sheff, David. All We Are Saying: The Last Major Interview with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. St. Martin's Griffin, 1981. Turner, Steve. A Hard Day's Write: The Stories Behind Every Beatles Song. itbooks, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2005.

4 Comments

|

Beatles BlogThis blog is a workshop for developing my analyses of The Beatles' music. Categories

All

Archives

May 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed