|

On 29 August 1966 at Candlestick Park in San Francisco, California, the Beatles played the final concert of what would be their very last performance tour. Many people thought the end of touring would be the demise of the band. John Lennon was one of them. "But I was really too scared to walk away. I was thinking, well this is like the end really. There's no more touring" (Anthology, Episode 6).

With touring no longer a concern, all four Beatles found themselves with a great deal of time on their hands. So, Paul undertook the project of writing music for the film The Family Way; George vacationed to India to take sitar lessons from Ravi Shankar; Ringo stayed at home – something the Beatles rarely did due to their grueling schedule – so he could spend time with his wife and their 1-year-old son, Zak; and John flew to Spain to act a minor role in Richard Lester's film How I Won the War. "I said yes to Dick Lester that I would make this movie with him and I went to Almería Spain for six weeks just because I didn't know what to do. What do you do when you don't tour? There's no life" (Anthology, Episode 6). The film is a black comedy about an inept and fictional regiment during World War II. It was intended as an anti-war protest - something that would dominate Lennon's own actions in the subsequent years - due to the escalating conflict in Vietnam. Lennon plays the role of Musketeer Gripeweed. The appearance of a Beatles has ensured its historical survival, but it seems otherwise forgettable. (It's available via instant streaming on Netflix as of February 2013.) Having acted in both A Hard Day's Night and Help! (both of which were also directed by Richard Lester), Lennon knew roughly what to expect. However, acting as an individual in a film is very different from acting as a band in a film and Lennon, notoriously impatient, quickly found himself quite bored. So he kept a guitar nearby to help pass the time between takes. It was in Spain, during the filming, that he began work on the song that would eventually become "Strawberry Fields Forever", originally titled “It's Not Too Bad”. CITATIONS Beatles. The Beatles Anthology. DVD. Apple Corps Limited, 2003.

0 Comments

Formal structure of [57] "I've Just Seen a Face":

Intro (ind) 0:00-0:11 Verse 1 0:11-0:23 Verse 2 0:23-0:35 Chorus 0:35-0:44 Verse 3 0:44-0:55 Chorus 0:55-1:03 Solo 1:03-1:15 Chorus 1:15-1:23 Verse 4 1:23-1:35 Chorus 1:35-1:43 Chorus 1:43-1:51 Chorus/Coda (verse) 1:51-2:05 Comments: I debated long and hard about calling the contrasting section a middle 8 or a chorus. Clearly it does contrast the verse (the primary characteristic of a middle 8), but it's not unheard of to substitute the chorus as the contrasting section. Middle 8s also frequently employ a harmonic shift (different or unusual chords) to emphasize their contrasting nature. In this case, I do not find a sufficient degree of harmonic contrast to justify calling this section a middle 8. Moreover, the section is used so frequently that the term chorus seems better suited to its structural function (middle 8s are generally heard twice per song - not six times, as is the case in this one). Like [166] "One After 909" and [94] "When I'm Sixty-Four", [46] "I'll Follow the Sun" was written well before the Beatles rise to fame. In a home session from 1960, the Quarrymen (they weren't the Beatles yet) recorded the tune, with McCartney singing lead, backed by a few guitars, some sort of percussion, and possibly a bass guitar. This version can be heard here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cgluqHpapIk.

The song wouldn't be released, however, until more than four years later in December 1964 with the release of Beatles for Sale. This later version can be heard here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=06RnXuZplyY. By the time of its commercial relase, the song - while still recognizable - sounded nothing like what it did in 1960. The 1960 version exudes bouncy, youthful enthusiasm, while the 1964 version features a more delicate, mature, and slightly weary sound. Structurally, the two featured completely different Middle 8s, with the former lyrics "Well, don't leave me alone, my dear, have courage and follow me my dear[?]"; and the latter lyrics "And now the time has come, and so my love I must go. And thought I lose a friend, in the end you will know." In no other single song is the Beatles development and progress more clearly heard than in "I'll Follow the Sun". Formal structure of [56c] "Bad Boy":

Intro (ind) 0:00-0:07 Verse 1 0:07-0:42 Verse 2 0:42-1:17 Solo 1:17-1:39 Verse 3 1:39-2:14 Coda 2:14-2:20 Comments: Each section except the intro is a 12 bar blues pattern. Perhaps the shortest coda of any Beatles song: a single chord. The Beatles made a total of five trips to Hamburg between 1960-1962, and it would be difficult to over-estimate the impact of those trips. John Lennon once said, “I grew up in Hamburg, not Liverpool” (Anthology, page 45), and sure enough, all five boys – who ranged in age from 17 to 22 – did a lot of growing up during those visits. The band as a whole grew, as well. As a result of the sheer quantity of time spent performing (they played for 6, 7, 8 hours a night, 7 days a week), the Beatles greatly improved their stage presence. "That's where we found our style," said George Harrison in the first espisode of The Beatles Anthology film. "We developed our style because of this fellow there - he used to say, "You've got to make a show for the people" and he used to come up every night yelling "Mach schau!". So we used to mach schau, and John used to dance around like a gorilla and we would all dance around and knock our heads together, and things like that". Also as a result of their grueling performance schedule, Hamburg was the Beatles introduced to drugs, specifically an amphetamine called Preludin. "The waiters always had Preludin (and various other pills, but I remember Preludin because it was a big trip) and they were all taking these pills to keep themselves awake, to work these incredible hours in this all-night place. And so the waiters, when they'd see the musicians falling over with tiredness or with drink, they'd give you the pill. You'd take the pill, you'd be talking, you'd sober up, you could work almost endlessly - until the pill wore off, then you'd have to have another" (Anthology, page 50). Similarly, the inevitable and frequent repetition of songs over the countless hours performing functioned as practice time, and all five musicians' technical facility on their instruments dramatically increased as a result. “I couldn't believe how much they'd changed since I'd last heard them play,” said Lennon's wife Cynthia after the Beatles returned from first Hamburg stint, “After so many hours of performing in Germany, they'd improved beyond all recognition. They'd gone from good to fantastic and the fans screamed with delight” (Lennon, page 62). But one bandmember lagged behind the others. While not a bad bass player, Stuart Sutcliffe never had the ability nor the determination to be a professional musician. He much preferred painting, at which he was exceptionally talented. As the other four Beatles improved by leaps and bounds, Stu realized it was time to call it quits, symbolically handing over his bass to Paul, who would forever more be the Beatles bassist. Stuart Sutcliffe, of course, wasn't the only bandmember change. Though Ringo Starr wouldn't join the band permanently for another few years, it was in Hamburg that he befriended John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and George Harrison. At the time, Ringo was the drummer in the band Rory Storm and the Hurricanes, who coincidentally had a similar job playing clubs in Hamburg. Though all four men were born and raised in Liverpool and knew of each other, it wasn't until their simultaneously gigs in Germany that the four bonded as companions. When this happened, Pete Best's days as a Beatle were numbered. Hamburg was also the location of the Beatles' first commercial recordings. The famed German record producer Bert Kaempfert attended one of their shows and was sufficiently impressed to invite the band to record as the backing group for singer Tony Sheridan. The Beatles ecstatically accepted the offer and recorded rock versions of "My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean" and "When the Saints Go Marching In". The single “My Bonnie”/“The Saints” was released in Germany, but the Beatles were not credited. Beatles sounds awfully similar to the word 'peedles', which is German schoolyard slang for male genitalia. Thus, the very first commercially released Beatles recording is actually credited to Tony Sheridan and the Beat Brothers.

Lastly, it was in Hamburg when the Beatles finally got their own recording break: an audition for George Martin of Parlophone Records, a division of Electric and Music Industries Ltd (EMI). On 9 May 1962, the band's manager, Brian Epstein, cabled the Beatles with the good news: “Congratulations boys. EMI request recording session. Please rehearse new material” (Spitz 312). CITATIONS Beatles. The Beatles Anthology. Chronicle Books, San Francisco, CA, 2000. Beatles. The Beatles Anthology. DVD. Apple Corps Limited, 2003. Lennon, Cynthia. John. Crown Publishers, New York, NY, 2005. Spitz, Bob. The Beatles: The Biography. Little, Brown and Company, Time Warner Book Group, New York, NY 2005. Formal structure of "Dizzy Miss Lizzy"

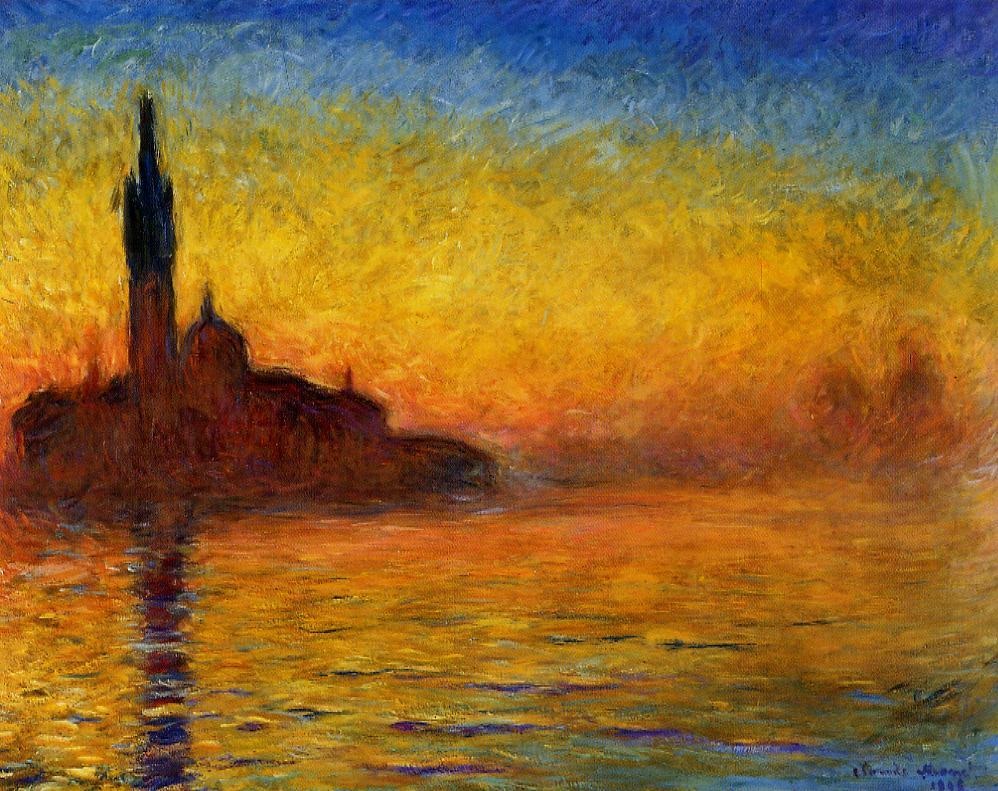

Intro (verse) 0:00-0:22 Verse 1 0:22-0:43 Verse 2 0:43-1:04 Solo/Break 1:04-1:25* Verse 3 1:25-1:47 Solo/Break 1:47-2:08* Verse 4 2:08-2:29 Verse 5 2:29-2:57 Comments: Two solos. The only other Beatles recordings to date to use multiple solos are [29b] "Long Tall Sally", [38] "I'm a Loser", [46b] "Everybody's Trying to be My Baby", and [46e] "Honey Don't". With all four Beatles preferring to do their own thing rather than work together, the last thing they wanted to do was another film. But they were under contract to complete three feature films (Magical Mystery Tour didn't count), and so when the notion of a cartoon was proposed – in which they wouldn’t have to act, or shoot scenes, or even record dialogue (actors were hired to provide the Beatles' voices) – they pounced. Of course, they still had to provide a soundtrack, and that generated no more enthusiasm than the film itself did. So they cobbled together a collection of previously released songs, rejects from other albums, and tunes thrown together in the studio. “It'll do for the film” John Lennon would say after a session they all knew was sub-par (Norman, page 326). The Beatles' 6 tracks on the Yellow Submarine soundtrack constituted the A-side of the album. But the real star of Yellow Submarine is only heard on the B-side, which feature orchestral tracks written George Martin. One track heard in the film, but not released until the Beatles Anthology shares striking similarities with the French composer Maurice Ravel's 1912 ballet Daphnis et Chloe. Here's the Ravel original (pay close attention to around 1:30). By writing this material, Martin is drawing a parallel between late 19th and early 20th century French Impressionism and 1960's pop psychedelia – both of which thrive on color. Take, for example, a Monet canvas. That same image in black and white loses a substantial amount of significance. (Lack of color is partially what doomed the premiere broadcast of Magical Mystery Tour, which likewise needs color to make any sense out of the surreal and psychedelic imagery.)

In writing this music and making that connection, then, George Martin - and not the Beatles - is the real star of Yellow Submarine. CITATIONS Norman, Philip. Shout! The Beatles in their Generation. Simon and Schuster, New York, NY, 1981. Formal structure of [56] "Help!":

Intro (chorus/ind) 0:00-0:11* Verse 1 0:11-0:31 Chorus 0:31-0:51 Verse 2 0:51-1:11 Chorus 1:11-1:32 Verse 3 1:32-1:52 Chorus 1:52-2:10 Coda (chorus/ind) 2:10-2:20* Comments: Very clear structure - no ambiguity. Introduction is partly based on chorus and partly independent: It shares the same chord progression (reduced in duration by 50%), but the words are independent (not found anywhere else in the song). Coda functions as an extension of the chorus, but with unrelated musical components. The Beatles' debut album Please Please Me functioned as a recording of a live show – its purpose to recreate what the Beatles did on stage, but in the comfort a listener's own home. Of course, as the band grew, they would develop into a studio band, and the beginnings of that evolution are first discernible in their sophomore album, With the Beatles. Overdubbing is the process of recording different parts of the same song at different times. It would make absolutely no sense at all in a concert setting to have, say, Paul play his bassline to “Roll Over Beethoven” as a solo, then when he was done George could sing his lead vocals by himself, then when he done Ringo could play his drums alone, followed by John's rhythm guitar chords. It'd be the equivalent of eating a piece of cake but on the first bite you taste only flour, and on the next only eggs, and the next just sugar. Of course that wouldn't work – whether in music or baking, all of the ingredients must be combined to render the final product. But in the studio, you can do that because the tapes can be combined through overdubbing, the layering of these various components into the final product. While a few minor tracks were overdubbed on Please Please Me, on With The Beatles it was quite heavily. For example, the piano solo in “Not a Second Time” was overdubbed. The Beatles recorded the guitar, bass, and drums, leaving a space for a solo because they weren't sure what that solo would be. Overdubbing allowed the band to come back to the song later and add a solo, in this case played by George Martin. Another recording tactic used frequently on With the Beatles was double-tracking, which is a particular kind of overdubbing in which the exact same thing is recorded twice, then layering on top of each other so they are heard simultaneously. The Beatles used this trick almost exclusively for lead vocals because the technique supplies reinforcement to whatever was double tracked, and lead vocals need to be strong. Obviously a singer can't sing his lines twice at the same time during a live show, but in the recording studio you can, and double-tracking is how that is accomplished. For example, Paul's singing on “All My Loving” is double tracked. You can tell because there are slight differences between takes – even though he's singing the same lyrics and notes. This is most noticeable on the word “I'll” as in “tomorrow I'll miss you”. The Beatles used double-tracking on 8 of the 14 tracks on With the Beatles ("It Won't Be Long", "All My Loving", "Don't Bother Me", "Little Child", "Please Mister Postman", "Roll Over Beethoven", "I Wanna Be Your Man", and "Not a Second Time") and would continue to do so throughout the remainder of their recording career. Additionally, the covers of the two albums showcase this change. Please Please Me's cover shows the four Beatles in a rather creative though quite "standard pop cover shot" pose. The With The Beatles cover, by contrast, is much more stark and artistic - and heavily inspired by the photographs taken by Astrid Kirchherr in Germany several years earlier. It's very subtle, but With the Beatles does show a significant change in direction from Please Please Me – a change that would eventually lead to the technical sophistication that so characterized the later Beatles albums.

Formal structure of [55] "You're Going to Lose That Girl":

Chorus 0:00-0:09* E Major Verse 1 0:09-0:23 E Major Chorus 0:23-0:30 E Major Verse 2 0:30-0:45 E Major Chorus 0:45-0:56 E Major Middle 8 0:56-1:10* G Major Solo 1:10-1:25 E Major Chorus 1:25-1:36 E Major Middle 8 1:36-1:49* G Major Verse 3 1:49-2:03 E Major Chorus 2:03-2:12 E Major Coda 2:12-2:20 E Major Comments: Begins with chorus instead of an introduction (like [12] "She Loves You", [14] "It Won't Be Long", [23] "Can't Buy Me Love", [34] "Any Time at All", [36] "When I Get Home", and [48] "Another Girl"), though in this case sans drum set (but with hand percussion). Also like "Another Girl" is the Middle 8 - in which both songs modulate to the lowered submediant (A Major to C Major in "Another Girl"; E Major to G Major in "You're Going to Lose That Girl"). This is the same modulation that the Beatles often use, and will culminate in the Abbey Road Medley (which uses that particular modulation extensively). |

Beatles BlogThis blog is a workshop for developing my analyses of The Beatles' music. Categories

All

Archives

May 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed