|

Barry Miles is the author of "The Beatles Diary, volumes 1 and 2", "Zappa: A Briography", "London Calling: A Countercultural History of London since 1945", "Hippie", "Jack Kerouac: King of Beats", "William Burroughs: El Hombre Invisible", and many other books. He co-founded the Indica Bookshop and Gallery, where John Lennon and Yoko Ono would meet for the first time; and was instrumental in the founding of International Times, a fortnightly periodical dedicated to the underground and avant-garde London art scene. He has maintained a lifelong friendship with Paul McCartney, and in 1994 published a biography of Paul titled "Paul McCartney: Many Years From Now". Once in an email to me, John Blaney, author of "John Lennon: Listen to This Book" and several other Beatles-related books, referred to Miles as "Mr. Avant-Garde", and indeed much of my Beatles and the avant-garde research is based on Miles' writing.

I am currently reading through his book "In the Sixties", which details his dealings with not only the Beatles, but also other bands/artists/musicians of the decade, in addition to providing details about his business endeavors like the International Times and Indica Bookshop & Gallery, and his troubles with the authorities regarding drug posession and obscentiy laws. This post, then, is a summary of this book, particularly as it relates to the Beatles, and particularly particularly how it relates to the Beatles and the avant-garde. All references and quotes refer to "In the Sixties" unless otherwise indicated. Full citations may be found at the end of this blog. Miles teamed up with John Dunbar in August 1965 with the intent of opening a bookshop/art gallery "to introduce people to new ideas and the latest developments in art" (p. 70, 116). Dunbar asked his best mate, Peter Asher (who achieved a substantial deal of fame and wealth through his music duo Peter & Gordon in 1964 with their number one hit ‘World Without Love’). to help fund the project. "Peter agreed to put up the £2,100 we thought we needed to start the bookshop and gallery by loaning John and me £700 each, and putting in the same amount himself. After many thoughtful pot-filled evenings, we decided to call the bookshop-gallery venture Indica, after Cannabis indica" (p. 68). Peter Asher lived in a house with his father Richard ("the first neurophysician to identify Munchausen’s syndrome, a condition in which people invent medical problems in order to draw attention to themselves"), mother Margaret (who "taught oboe at the Guildhall School of Music, and often had her students over for lessons in the basement music room. George Martin, the Beatles’ producer, had been one of her students, as was Paul McCartney"), and two sisters Clare and Jane, the latter of whom just so happened to be dating Paul McCartney (p. 72-73) Paul and Jane met on 18 April 1963, at a social gathering following a performance at London's Royal Albert Hall. All of the Beatles knew Jane Asher - she was at the time just as famous as they were for her performances as an actress - but this was the first time they had met in person. Lennon took an immediate interest in her, and (presumably under the influence of alcohol) made crude sexual references towards her. Paul, no doubt sensing his own opportunity, rose to Jane's defense, and the two left the party arm in arm. They started dating shortly thereafter. (Carlin p. 87-88). When McCartney wasn't busy, he offered to help prepare the Indica for its opening, "hammering and sawing, filling in the holes in the plaster and helping to erect bookshelves. ... [R]umors spread and soon everyone in the nearby shops and galleries knew all about the Beatles’ new art gallery" (p. 81). The Indica opened its doors in September 1965 - it's first customer being Paul McCartney, who purchased "And It’s a Song, poems by Anselm Hollo; Drugs and the Mind by DeRopp; Peace Eye Poems by Ed Sanders; and Gandhi on Non Violence. This showed both his range of interest and the type of stock I was buying" (p. 74). The following March, McCartney brought John Lennon to the Indica. "He scanned the shelves and soon came upon The Psychedelic Experience, Timothy Leary’s psychedelic version of the Tibetan Book of the Dead. ... On page fourteen of Leary’s introduction he came upon the line ‘Whenever in doubt, turn off your mind, relax, float downstream’. With only slight modification, this became the first line of ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, the Beatles’ first truly psychedelic song" (p. 113). In September 1966, London hosted a "Destruction in Art Symposium", inviting Yoko Ono (among many others) to participate. Impressed with her work, John Dunbar offered her an exhibition at the Indica Gallery, and scheduled it to open on 9 November 1966. John Dunbar, now friends with John Lennon from his visits to the Indica, invited the Beatle to visit the exhibition the night before it opened to the public, and it was there that John Lennon and Yoko Ono met for the first time. The avant-garde scene of the time was notoriously negative and pessimistic - and John despised it intensely. Indeed, the very engagement that brought Ono to London in the first place was the "Destruction in Art Symposium", in which "Otto Muhl skinned a lamb and covered everyone with blood, and Ralph Ortiz, a tall Puerto Rican artist, chopped Jay Landesman’s piano to pieces" (p. 144). Anticipating similarly negative art, Lennon admitted how close he was to walking out of the gallery when one of the first artworks he observed was a step ladder leading to an unintelligibly tiny word written on the ceiling. Hanging down from the ceiling was a magnifying glass to be used to read the infinitesimal text. Lennon held up the magnifier and read the word, “yes”. Quoting Lennon: “If it had said ‘No’, or something nasty like ‘rip off’ or whatever, I would have left the gallery then. Because it said ‘Yes’, I thought, Okay, this is the first show I’ve been to that said something warm to me" (Solt p. 120). Though it would take two years before John and Yoko established their romantic relationship, the moment when he decided to stay at her exhibition would prove to be the most pivotal point in Beatles history. Once John found Yoko, she completely eclipsed Paul as John’s primary artistic collaborator. With John now more interested in Yoko than the Beatles, Paul was able to replace him as leader of the group; and with the introduction of a full-fledged avant-garde artist, Paul’s involvement and enthusiasm for the movement abated, freeing John to adopt the role. Citations: Carlin, Peter Ames. Paul McCartney: A Life. Touchstone Book, Simon & Schuster, New York, NY, 2009. Miles, Barry. In the Sixties. Jonathan Cape, London, UK, 2002. Solt, Andrew and Sam Egan. Imagine John Lennon. Penguin Studio, Sarah Lazin Books, New York, NY, 1988.

0 Comments

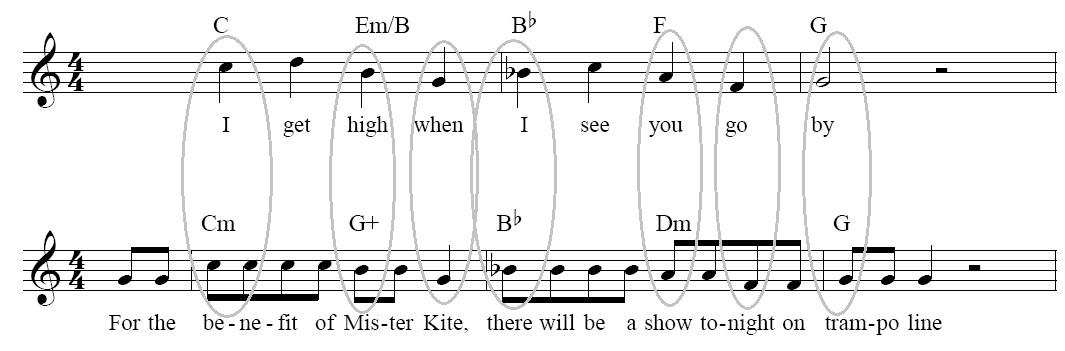

"It's Only Love" (from the album Help!) and "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite" (from the album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band) feature striking melodic similarities. Both tunes land on the note c, then gradually step down by half-step to b-natural, then b-flat. In between, both share the note g in the first measure, and d in the second. And the final melodic notes in both songs is g. The underlying chords are also very similar. Both start on C (though the former C major while the latter C minor), then on next measure on B-flat major, and on the third measure G major. In between, the chords are related, but not identical. The chord Em/B uses the notes b-e-g, while G+ uses g-b-d#. Both of these chords share the notes b and g, so they are quite similar. The chord F uses the notes f-a-c, while Dm uses d-f-a. Here, again, these chords share two notes - in this case f and a - so they, too, are quite similar. Here are both melodies and chords written in lead-sheet notation, "It's Only Love" on top, "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite" on the bottom: For an audio example, click here. First the melody from "It's Only Love" is heard, then the melody from "Mr. Kite", and finally the two layered on top of each other.

Paul McCartney's inventive and melodic playing elevated the lowly bass to iconic levels, but some of his basslines are inspired/borrowed/stolen from others' work.

The bassline in "Drive My Car" is taken from Otis Redding's "Respect". The chord progressions are different, but the melodic patternand rhythm within each measure are the same. The bassline in "I Saw Her Standing There" is taken from Chuck Berry's "I'm Talking About You", which the Beatles covered during their long Hamburg stints. Here is a live recording from 1962 of the Beatles performing "I'm Talking About You" at the Top Ten Club in Hamburg - with Paul playing the exact same bassline he would borrow two years later. I have often been harshly critical of such blatant theft (I have often called John Williams a "musical kleptomaniac"), but I've been much more understanding of "borrowing" in the past few years as I've realized that all composers take what others have done and add to it/edit it to "make it their own". As Igor Stravinsky famously said, "Good composers borrow, great composers steal." I have done several posts on the use of minor dominants in early Beatles music (as used in "From Me To You" on 11/17, in "Do You Want to Know a Secret" on 11/22, and in "I Want to Hold Your Hand" on 11/23). To illustrate through side-by-side comparisons, I created MIDI examples showing what these various songs sound like using both major and minor dominant chords. This blog, then, will reverse the concept: Instead of illustrating what songs that use minor dominants would sound like had they chosen to use major dominants, here are several early Beatles songs that use major dominants with examples of what they would have sounded like had they chosen to use minor dominants.

"Love Me Do" Excerpt with major dominant Excerpt with minor dominant "Hold Me Tight" Excerpt with major dominant Excerpt with minor dominant "Thank You Girl" Excerpt with major dominant Excerpt with minor dominant "Please Please Me" Excerpt with major dominant Excerpt with minor dominant Most listeners are probably familiar with "From Me To You", "Do You Want to Know a Secret", and "I Want to Hold Your Hand" - but it is precisely that familiarity that masks the unusualness of the progression. The excerpts above provide more obvious examples of how strange this particular chord really is (or at least, was for the early 1960's). As further follow-up to the minor dominants discussed in the past week, there's one more song that makes significant use of the minor dominant chord: "I Want to Hold Your Hand". Paul's comments on "From Me To You" (see my post from Nov 17) reveal his fascination with the minor dominant chord. He was apparently quite pleased with it, because he and Lennon used it again in "I Want to Hold Your Hand".

Here are MIDI examples, again, to show the difference: First with the minor dominant, the second with an altered major dominant. This difference, however, is much, much more subtle than the previous MIDI examples (see blogs from 11/17 and 11/22) because even though it's the same difference (side-by-side comparisons of the same passage, one using a major dominant, the other using a minor dominant), the melody in "I Want to Hold Your Hand" does not reinforce this difference. In other words, the melodies in "From Me To You" and "Do You Want to Know a Secret" change when the underlying chord structure changes, thus making those differences very easy to hear; but in "I Want to Hold Your Hand", the melody is identical regardless of what quality of dominant chord is used, thus making the difference in dominant quality much less discernible. Continuing the theme from my last few blogs of minor dominant chords used in early Beatles' recordings, this one will look at "Do You Want To Know a Secret" because despite Paul citing "From Me To You" as the first Beatles song to use a minor dominant (see 11/17 post), that title actually belongs to "Do You Want to Know a Secret". But, since "Secret" is more of a Lennon number than a McCartney one, perhaps Paul was unaware of that fact.

Throughout all of the verses of "Secret", the dominant is always a dominant seventh - in this case B7. In the middle 8 ("I've known a secret for a week or two/Nobody knows, just we two"), however, we hear minor dominants (B minor) on both iterations of the word "two". Listen to these two MIDI examples, the first of which using the minor dominant (as is heard in the final product), the second of which uses the more common major dominant. The difference is subtle but significant. As a side note, the opening lines of the first verse ("Do you want to know a secret? Do you promise not to tell?") are taken nearly word for word from the song "I'm Wishing" from the 1937 Disney film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Julia, John's mother, used to sing him the Disney tune as a lullaby. Though "I'm Wishing" bears no musical resemblance, the lyrics made their way into Lennon's rock song. As a follow-up to my previous post, this one will look specifically at the use of the minor dominant chord in "From Me To You".

"I remember being very pleased with the middle eight because there was a strange chord in it, and it went into minor: 'I've got arms that long...' We thought that was a very big step." -Paul McCartney, Anthology p. 94 The "strange chord" McCartney refers to is an A minor chord. But an A minor chord in an of itself is nothing terribly original or innovative (or strange) - A minor chords appear in "Misery", and "Do You Want to Know a Secret" from their studio recordings prior to "From Me To You", and undoubtedly in many more of their early concert songs that were never recorded in-studio. What was new was the tonal context for that A minor chord. "From Me To You" is in D major, and in that tonality A minor is an unusual chord. The technical term for this is a minor dominant (a dominant being the chord based on the fifth scale degree - in D major, this would be the note A). A major (the major dominant) is much more common because it's more closely related to D major. The D major scale consists of the notes D-E-F sharp-G-A-B-C sharp-D. An A major chord consists of the notes A-C sharp-E, and an A minor chord consists of A-C (natural)-E. The A major chord, then, is more-closely related to the D major scale because all three notes that comprise the A major chord are also found in the D major scale. The A minor chord, on the other hand, is less-closely related to the D major scale because only 2 of the 3 notes are shared - both A and E are common between the two, but the C natural is not. To aurally illustrate the difference, listen to these two MIDI renditions: the first being the version using the minor dominant (as it actually appears on the recording), the second what it would have sounded like with the more common major dominant. The more unusual chord will likely sound more normal out of habit (we've all heard "From Me To You" so many times that any change to the chord structure will probably stick out like a sore thumb). However, as my previous post shows quite conclusively, the Beatles were much, much more likely to use the major dominant than the minor. Re-organizing the information from my previous blog to show how one-sided this is, here it is again, grouped by use rather than chronologically: Songs that use major dominants exclusively (41 total): Love Me Do: G major, only D major chords (no D minor chords) P.S. I Love You: D major, only A major chords (no A minor chords) Please Please Me: E major, only B major chords (no B minor chords) Ask Me Why: E major, only B major chords (no B minor chords) I Saw Her Standing There: E major (although D naturals suggest E mixolydian), only B major chords (no B minor chords) Misery: C major, only G major chords (no G minor chords) Anna (Go To Him): D major, only A major chords (no A minor chords) Chains: B-flat major, only F major chords (no F minor chords) Boys: E major, only B major chords (no B minor chords) Baby it's You: G major, only D major chords (no D minor chords) There's a Place: E major, only B major chords (no B minor chords) Twist and Shout: D major, only A major chords (no A minor chords) Thank You Girl: D major, only A major chords (no A minor chords) She Loves You: G major, D majors and D7 (with a flat 6th), no D minors It Won't be Long: E major, only B major (7) chords, no B minors All My Loving: E major, all B and B7 chords Till There Was You: F major, all C major chords except one C+ and a few either Gm7/C or C11(-3) Little Child: E major (mixolydian?), all B7 chords Please Mister Postman: A major, all E chords are major (no E minor chords) Roll Over Beethoven: D major, all A chords are major (in fact, every single chord in the whole song is major - there are no minor chords at all!) Hold Me Tight: F major, all dominants are dominant seventh chords You've Really Got a Hold on Me: A major, all E chords major, and sometimes 7 I Wanna Be Your Man: E major (mixolydian?), all B chords major, and sometimes 7 Devil in her Heart: G major, all D's are dominant 7 chords Not a Second Time: G major, dominants used sparingly, all D majors, and sometimes 7 Money (That's What I Want): E major (mixolydian?), every single B chord is a V7 This Boy: D major, every A chord is a V7 Long Tall Sally: G major, every D is a V7 I Call Your Name: E major (mixolydian?), every B is a V7 Slow Down: C major, all G chords are V Matchbox: A major (mixolydian?), all E chords are V7 A Hard Day's Night: G major, the famous first chord functions (sort of) as a dominant. But it could also be a tonic with the 5th in the bass. Rather similar to the "Appalachian Spring Chord" in that the sense of harmonic propulsion is attenuated by elements of both tonic and dominant chords sounding simultaneously. Throughout the verses, choruses, and middle 8, the dominant is used quite sparingly - always as V or V7. I Should Have Known Better: G major, lots of D chords - all V or V7 If I Fell: D major, several A chords - all V7 I'm Happy Just to Dance With You: E major, several B chords - V, V7, V7+, Vadd6 Tell Me Why: D major, standard V7 chords until coda which features a V11 and V13 Can't Buy Me Love: C major, several V7 chords and a smattering of Vadd6 chords Any Time At All: D major, standard V and V7 I'll Cry Instead: G major, a couple V7 chords and a great many V11(-3) chords - the same chord found in "Til There Was You" When I Get Home: C major,all V7 I'll Be Back: A major (could make a case for minor), the dominant (always V - never V7 always resolves to A major Songs that use both major and minor dominants (6 total): Do You Want to Know a Secret: E major, mostly B major chords but a few B minors in the middle 8. B minor hinted at in introduction. From Me To You: C major, G major in verses but minor in middle 8 (plus one G+) I'll Get You: D-flat major, mostly A-flat (7), occasional A-flat minors Don't Bother Me: E minor, mostly B major and B7, a few B minors I Want to Hold Your Hand: G major, D chords are major in the verses and choruses, but minor in the middle 8s. (Just like "From Me To You".) Things We Said Today: A minor during verses but A major in the middle 8; v7 common in verses, V7 used in middle 8. Songs that use minor dominants exclusively (0 total): [none] Songs that use no dominant whatsoever (1 total): All I've Got to Do: E major, not a single dominant chord is used Ambiguous (3 total): A Taste of Honey: F-sharp minor, ?. I'm gonna come back to this one. And I Love Her: tonality ambiguous. I'm gonna come back to this one You Can't Do That: G major (mixolydian?), all V7 but lots of bent thirds, making major/minor difficult to discern Thus, of the Beatles' first 51 commercially recorded and released tracks, 41 use major dominants exclusively (82%), 6 use both major and minor dominants (12%), 0 use minor dominants exclusively (0%), 1 uses no dominant whatsoever (2%), and 3 are ambiguous (6%). Tunes using only major dominants are therefore 6.83 times more common than tunes using both major and minor dominants. This is what Paul McCartney was referring to when he claimed the use of a minor dominant in "From Me To You" was "strange". How the Beatles used the dominant chord in their studio recordings through "A Hard Day's Night"11/16/2012 Paul has made comments about the use of a minor dominant chord in "From Me To You". Those comments have prompted me to create a song-by-song index to see exactly how the Beatles used the dominant chord.

Title: tonality of song, use of dominant chords with particularly interesting or unusual instances italicized. Love Me Do: G major, only D major chords (no D minor chords) P.S. I Love You: D major, only A major chords (no A minor chords) Please Please Me: E major, only B major chords (no B minor chords) Ask Me Why:F E major, only B major chords (no B minor chords) I Saw Her Standing There: E major (although D naturals suggest E mixolydian), only B major chords (no B minor chords) Misery: C major, only G major chords (no G minor chords) Anna (Go To Him): D major, only A major chords (no A minor chords) Chains: B-flat major, only F major chords (no F minor chords) Boys: E major, only B major chords (no B minor chords) Baby it's You: G major, only D major chords (no D minor chords) Do You Want to Know a Secret: E major, mostly B major chords but a few B minors in the middle 8. B minor hinted at in introduction. A Taste of Honey: F-sharp minor, ?. I'm gonna come back to this one. There's a Place: E major, only B major chords (no B minor chords) Twist and Shout: D major, only A major chords (no A minor chords) From Me To You: C major, G major in verses but minor in middle 8 (plus one G+) Thank You Girl: D major, only A major chords (no A minor chords) She Loves You: G major, D majors and D7 (with a flat 6th), no D minors I'll Get You: D-flat major, mostly A-flat (7), occasional A-flat minors It Won't be Long: E major, only B major (7) chords, no B minors All I've Got to Do: E major, not a single dominant chord is used All My Loving: E major, all B and B7 chords Don't Bother Me: E minor, mostly B major and B7, a few B minors Little Child: E major (mixolydian?), all B7 chords Till There Was You: F major, all C major chords except one C+ and a few either Gm7/C or C11(-3) Please Mister Postman: A major, all E chords are major (no E minor chords) Roll Over Beethoven: D major, all A chords are major (in fact, every single chord in the whole song is major - there are no minor chords at all!) Hold Me Tight: F major, all dominants are dominant seventh chords You've Really Got a Hold on Me: A major, all E chords major, and sometimes 7 I Wanna Be Your Man: E major (mixolydian?), all B chords major, and sometimes 7 Devil in her Heart: G major, all D's are dominant 7 chords Not a Second Time: G major, dominants used sparingly, all D majors, and sometimes 7 Money (That's What I Want): E major (mixolydian?), every single B chord is a V7 I Want to Hold Your Hand: G major, D chords are major in the verses and choruses, but minor in the middle 8s. (Just like "From Me To You".) This Boy: D major, every A chord is a V7 Long Tall Sally: G major, every D is a V7 I Call Your Name: E major (mixolydian?), every B is a V7 Slow Down: C major, all G chords are V Matchbox: A major (mixolydian?), all E chords are V7 A Hard Day's Night: G major, the famous first chord functions (sort of) as a dominant. But it could also be a tonic with the 5th in the bass. Rather similar to the "Appalachian Spring Chord" in that the sense of harmonic propulsion is attenuated by elements of both tonic and dominant chords sounding simultaneously. Throughout the verses, choruses, and middle 8, the dominant is used quite sparingly - always as V or V7. I Should Have Known Better: G major, lots of D chords - all V or V7 If I Fell: D major, several A chords - all V7 I'm Happy Just to Dance With You: E major, several B chords - V, V7, V7+, Vadd6 And I Love Her: tonality ambiguous. I'm gonna come back to this one Tell Me Why: D major, standard V7 chords until coda which features a V11 and V13 Can't Buy Me Love: C major, several V7 chords and a smattering of Vadd6 chords Any Time At All: D major, standard V and V7 I'll Cry Instead: G major, a couple V7 chords and a great many V11(-3) chords - the same chord found in "Til There Was You" Things We Said Today: A minor during verses but A major in the middle 8; v7 common in verses, V7 used in middle 8. When I Get Home: C major,all V7 You Can't Do That: G major (mixolydian?), all V7 but lots of bent thirds, making major/minor difficult to discern I'll Be Back: A major (could make a case for minor), the dominant (always V - never V7 always resolves to A major A few brief conclusions: The dominant chord, so integral to common-practice functional tonality and classical harmony, is really not that important in the Beatles' oeuvre. Far more significant are chords rooted on the fourth and sixth scale degrees. Perhaps some time I'll do an index for them, too. "Yesterday" is one of the Beatles' most famous and recognizable songs. And its background and development is one of the more fascinating and amusing stories of any Beatles recording.

The melody came to Paul in a dream sometime in late 1963 or early 1964 - he called it a gift from his subconscious. Paul, as quoted in the Beatles Anthology: "I woke up one morning with a tune in my head and I thought, 'Hey, I don't know this tune - or do I?' It was like a jazz melody. My dad used to know a lot of old jazz tunes; I thought maybe I'd just remembered it from the past. I went to the piano and found the chords to it, made sure I remembered it and then hawked it round to all my friends, asking what it was: 'Do you know this? It's a good little tune, but I couldn't have written it because I dreamt it.' " (Anthology, p. 175) To make sure he remembered the tune, Paul put ridiculous lyrics to the melody ("Scrambled eggs, oh my baby how I love your legs") and started to play it for a variety of people to see if anybody could place the melody. Two such people were Dick James, who published the Beatles' songs, and Chris Hutchins, editor of Disc magazine. This is amusingly depicted in Peter Ames Carlin's biography of Paul McCartney: "[I]t didn't impress Dick James at all. 'Dick's face fell,' Hutchins says. 'And he said, "Have you got anything with yeah, yeah, yeah in it?" ' And Paul was shattered." (Carlin, p. 95) Once Paul figured out that the melody was original - that he hadn't inadvertently stolen it - he then had to decide what to do with it. It certainly wasn't standard Beatles material, so he started offering the song to other singers to record. (I seem to recall reading somewhere that Paul offered the song to Marianne Faithful, but I have been unable to locate any evidence for that notion. If he did offer it to Faithful, she either declined or failed to record it before the Beatles did.) In "The Beatles Diary, Volume 1: The Beatles Years", author Barry Miles quotes from Eric Burdon's autobiography an account between Burdon and blues singer Chris Farlowe about McCartney offering Farlowe the song: "One day he [Farlowe] phoned me at my Duke Street pad. 'Hey Eric, how ya doin', it's Chris Farlowe here,' he said in his hoarse voice. I asked how he was getting on. 'Oh, I'm OK. 'Ere listen, you'll never guess what happened. Paul McCartney - you know Paul out of the Beatles?' Yes, I had heard of him. 'Well he came round to our house in the middle of the night. I was out doing a show, but me mum was in and he left her a demo disc for me to listen to.' This was wonderful news. When was Chris going into the studio to cut this gift from the gods? 'Ah,' he growled. 'I don't like it. It's not for me. It's too soft. I need a good rocker, you know, a shuffle or something.' 'Yeah, but Chris,' I said. 'Anything to give you a start, man, I mean even if it's a ballad, you should go ahead and record it.' 'No, I don't like it,' he inssited. 'Too soft.' 'So what are you gonna do with the song?' 'Well, I sent it back, didn't I?' 'What was the title of the song?' 'Yesterday.' " (Miles, p. 211) The first take, recorded at Abbey Road Studios on June 14, 1965, features Paul singing and playing a finger-picking pattern on an acoustic guitar. George Martin suggested adding strings as accompaniment, but Paul disliked the idea. He seriously considered an electronic backing, going as far as contacting Delia Derbyshire of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop to inquire about the possibility. Derbyshire is best-known for composing the theme song to Dr. No. But the notion of an electronic accompaniment was eventually scrapped, and Martin's suggestion of strings was adopted - but Paul insisted on a string quartet (rather than orchestra) playing with absolutely no vibrato because he didn't want it to sound like Mantovani. (Probably to his chagrin, Mantovani did record a cover.) The Beatles' final version, as it appears on Help!, features a string quartet in addition to Paul's vocals and guitar playing. Marriane Faithful and Chris Farlowe both recorded covers - but only after the Beatles' recording was released and achieved tremendous acclaim and success. "Yesterday" has gone on to be the most-covered song in history. In 1980 Paul called it "probably my best song. I like it not because it was a big success, but because it was one of the most instinctive songs I've ever written. I was so proud of it. I felt it was an original tune - the most complete thing I've ever written. It's very catchy without being sickly." (Miles, p. 205) Steve Turner notes another anecdote about "Yesterday" in his book "A Hard Day's Write: The Stories Behind Every Beatles Song": "Iris Caldwell remembered an interesting incident in connection with the song. She had broken up with Paul in March 1963 . . . and, when he later called up to speak to Iris, her mother told Paul that her daughter didn't want to speak to him because he had no feelings. Two and a half years later, on Sunday August 1, 1965, Paul was scheduled to sing 'Yesterday' on a live television programme, Blackpool Night Out. During that week, he phoned Mrs Caldwell and said, 'You know that you said that I had no feelings? Watch the telly on Sunday and then tell me that I've got no feelings.' " (p. 84) Citations Beatles. The Beatles Anthology. Chronicle Books, San Francisco, CA, 2000. Carlin, Peter Ames. Paul McCartney: A Life. A Touchstone Book, published by Simon & Schuster, New York, NY, 2009. Miles, Barry. The Beatles Diary, Volume 1: The Beatles Years. Omnibus Press, New York, NY, 2001. Turner, Steve. A Hard Day's Write: The Stories Behind Every Beatles Song. It Books, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers, New York, NY, 2005. Lyrically, I Want to Hold Your Hand grows out of previous Beatles songs. Take, for example, the lines "You got that something/I think you'll understand/When I feel that something/I want to hold your hand". The second of these lines is similar in a "wink-wink-nudge-nudge" way to the second line from I Saw Her Standing There: "Well she was just seventeen/You know what I mean". Furthermore, the lyrics of I Want to Hold Your Hand display the same degree of sexual frustration as found in Please Please Me. Certainly the singer in the former wants the girl to do more than just hold his hand, just as the singer in the latter urges his lover: "You don't need me to show the way love/Why do I always have to say, love/Come on, come on, come on, come on/Please please me like I please you".

P.S. Aaron Copland was born 112 years ago today. Michael Schelle, one of my teachers and mentors during my undergraduate years at Butler University, studied with Copland in the 70's. |

Beatles BlogThis blog is a workshop for developing my analyses of The Beatles' music. Categories

All

Archives

May 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed