|

No Reply

I'm a Loser

Baby's in Black

Rock and Roll Music

I'll Follow the Sun

Mr. Moonlight

Kansas City/Hey Hey Hey Hey

Eight Days a Week

Words of Love

Honey Don't

Every Little Thing

I Don't Want to Spoil the Party

What You're Doing

Everybody's Trying to Be My Baby

0 Comments

Formal structure in [44b] "Kansas City/Hey Hey Hey Hey"

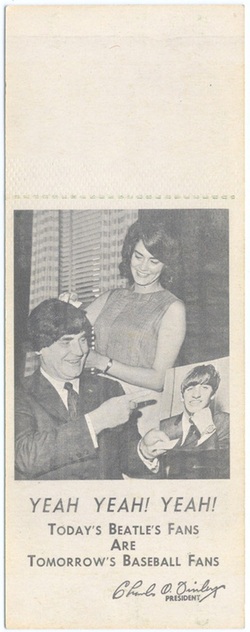

Intro (ind) 0:00-0:08 Verse 1 0:08-0:29 Verse 2 0:29-0:51 Solo 0:51-1:13 Chorus #1 1:13-1:35 Chorus #1 1:35-1:57 Chorus #2 1:57-2:19 Chorus #2/Coda 2:19-2:37* Comments: This one is unique in that it combines two completely different songs: "Kansas City", written by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller in 1952; and "Hey Hey Hey Hey" written by Richard Penniman (a.k.a. Little Richard), who liked to combine it with the Leiber/Stoller song in live performances to create a medley. The Beatles, who heard "Kansas City/Hey Hey Hey Hey" on the B side of Little Richard's single "Good Golly Miss Molly" (released 1958), adopted the medley for their own by 1962, dropped it from their set list in 1963, and then revived the song in preparation for a performance in Kansas City on September 17, 1964. Perhaps out of need for additional songs rather than artistic merit, the medley was recorded and added to the album Beatles for Sale, released 1964. Point is that from a structural point of view, it's rather difficult to analyze precisely because it's actually two songs stuck together. Though it's clearly open to debate, for the sake of simplicity I have analyzed the "Hey Hey Hey Hey" section as two choruses (they share nearly identical chord progressions and durations - it's only the lyrics that differ) each with a repeat. The very last section fades to nothing, making it both an iteration of the second chorus and a coda.  In preparation for my LifeLearn Baseball course (debuting Spring 2013), I have been reading Charlie Finley: The Outrageous Story of Baseball's Super Showman by G. Michael Green and Roger D. Launius. I was aware, of course, of the Beatles' performance in Kansas City during the fall of 1964 American Tour, and that this performance prompted the band to perform the song "Kansas City", which they later recorded and released on the album Beatles for Sale. In other words, I knew of the concert from the band's perspective. What I did not know was the story from the ball club's perspective. This blog, then, will fill that gap. In 1965, Municipal Stadium was home to the Kansas City Athletics, who moved from Philadelphia in 1955. (The current KC baseball team is the Royals, who played their inaugural season in 1969 as an expansion team following the Athletics' move to Oakland a year prior.) The Athletics' owner was Charles Oscar Finley, an irascible and controversial man who would between 1972-1974 lead his team (by then the Oakland Athletics) to three consecutive World Series titles. Though he always denied it, as early as 1961 (his first season as owner) Finley had plans to move the franchise. This naturally caused irreparable damage in the minds of KC baseball fans (especially after blatantly lying about it). In a rare effort to mend public relations, Finley hired the Beatles to perform at his stadium. On the back of each ticket was a photo of Finley wearing a Beatles wig, pictured right. The band played a 31-minute set on September 17, 1964 to an audience of 20,280. Municipal Stadium, however, held 34,165, and 28,000 tickets would have had to sell to break even. "Kansas City was the only concert venue on the tour that didn't sell out. Many potential concertgoers stayed way after the Kansas City Star and others urged a boycott of the concert as a way of showing displeasure with Finley. Finley promised to give all of his after-expenses profits to a local charity, Children's Mercy Hospital, but because the concert did not sell out, Finley actually lost money - possibly becoming the first Beatles concert promoter ever to do so" (Green, page 77). Finley, however, in an attempt to put as positive a spin on it as possible, insisted "I don't consider it any loss at all. The Beatles were brought here for the enjoyment of the children in this area and watching them last night they had complete enjoyment. I'm happy about that. Mercy Hospital benefited by $25,000. The hospital gained, and I had a great gain by seeing the children and the hospital gain" (Miles, page 171). Some, though, did make money on the Beatles' KC visit, "especially the two people who acquired the bedsheets from the Beatles hotel rooms, which they then cut into small squares to sell as souvenirs. They netted $159,000 for their efforts" (Green, page 77) after purchasing the 16 sheets and 8 pillowcases for just $750 (Miles, page 171). Die hard Beatles fans may recall a similar incident in Robert Zemeckis' 1978 film I Wanna Hold Your Hand. Citations Green, Michael G. and Roger D. Launius. Charlie Finley: The Outrageous Story of Baseball's Super Showman. Walker & Company, New York, NY, 2010. Miles, Barry. The Beatles Diary, Volume 1: The Beatle Years. Omnibus Press, A Division of Book Sales Limited, New York, NY, 2001. The basic formula of a 12 bar blues progression, as written in Roman numerals with each character representing one measure, is as follows:

I I I I IV IV I I V IV I I This pattern can, of course, be used in any key. Below are 5 examples in C major: in D major: in E major: in G major: in A major: C C C C D D D D E E E E G G G G A A A A F F C C G G D D A A E E C C G G D D A A G F C C A G D D B A E E D C G G E D A A 27 songs recorded and released by the Beatles use a 12 bar blues progression or something comparable. Of those 27, 15 were original compositions and 12 were covers. Below are all 28 tracks, listing their year of release, tonality, a concise harmonic analysis, and brief commentary. [9c] "Boys" (1963) E major E7 E7 E7 E7 A7 A7 E7 E7 B7 A7 E7 B7 It is clearly modeled on the 12 bar blues - the only alterations being (a) every chord is a seventh chord (making each chord slightly more dissonant and gritty sounding), and (b) the very last chord is B (the dominant in E major) instead of the traditional E. No doubt this is because B7 leads very nicely to E, which starts the progression all over again. [9d] "Chains" (1963) Bb major Bb Bb Bb Bb Eb9 Eb9 Bb Bb F9 Eb9 Bb F Another clearly modeled on the 12 bar blues. The only alterations are (a) a few ninths are added to a few chords, and (b) the very last chord is F (the dominant in Bb), which of course leads strongly back to Bb to start the progression all over again. [13c] "Money (That's What I Want)" (1963) E major E7 E7 (A) E7 E7 A7 A7 E7 E7 B7 A7 E7 B7 In addition to adding sevenths to every chord, "Money" also adds an extra A chord in the second measure of each verse. This chord is listed in parentheses above because unlike every other chord listed above it does not represent a full measure. (If it did, it would make this a 13 bar blues pattern instead of 12.) Rather, it represents a brief instrumental fill (listen right after the words "life are free") that embellishes the 12 bar blues progression but does not interfere in any way with its function. [14b] "Roll Over Beethoven" (1963) D major D7 G7 D7 D7 G7 G7 D7 D7 G7 A7 D7 D7 In addition to adding sevenths to every chord, "Roll Over Beethoven" also replaces the second chord (which 'should' be D7) with a G7. The 9th and 10th bars are also reversed (G7 A7 instead of A7 G7). [17] "Little Child" (1963) E major E7 E7 E7 (A) E7 B7 A F#7 (B7) E The most significant departure from the mold that is still clearly based on the mold, "Little Child" turns the 12 bar blues into an 8 bar blues for the verses. It omits measures 4-8 and replaces them with 9-12. But those measures offer something new as well when an F#7 (which has no place in a normal 12 bar blues) is used in the 11th measure. The solo section, however, adopts a more usual 12 bar pattern . . . E7 E7 E7 E7 A A E7 E7 B7 A F#7 B7 . . . although it still is hardly standard with the added F#7 in the 11th measure and yet another dominant chord in the 12th. [23] "Can't Buy Me Love" (1964) C major C7 C7 C7 C7 F7 F7 C7 C7 G7 F7 F7 C7 The only substantial deviation from the model is using an F chord in bar 11 (instead of the more typical C). [24] "You Can't Do That" (1964) G major G7 G7 G7 G7 C7 C7 G7 G7 D7 C7 G7 D7 Just like [9c] "Boys", [9d] "Chains", [13c] "Money (That's What I Want)", and [17] "Little Child", "You Can't Do That" uses a typical 12 bar blues progression except for the very last chord, which is changed to a dominant to heighten the harmonic tension and release when the pattern is repeated. [29b] "Long Tall Sally" (1964) G major G G G G C C G G D7 C7 G D7 The comments above regarding [24] "You Can't Do That" may be iterated in regards to [29b] "Long Tall Sally". [31b] "Matchbox" (1964) A major A7 A7 A7 A7 D7 D7 A7 A7 A7 E7 A7 E7 The only significant deviations from the mold are the 9th through 12th bars (A7 E7 A7 E7 - again ending with a dominant chord - instead of the more typical E D A A). [32b] "Slow Down" (1964) C major C C C C C C C C F F F F C C C C G F C C C C C C "Slow Down" takes the 12 bar blues and augments it into a 24 bar blues. The first 16 measures of "Slow Down" are simply the first 8 measures of a normal 12 bar blues doubled (but proportionally maintained); and the last 8 measures of "Slow Down" are just the last 4 measures of normal 12 bar blues with 4 extra bars of C grafted on to the end. [44] "She's a Woman" (1964) A major A7 D7 A7 A7 A7 D7 A7 A7 D7 D7 D7 D7 A7 D7 A7 A7 E7 E7 D7 D7 A7 D7 A7 E7 Just like [32b] "Slow Down", "She's a Woman" takes the 12 bar blues progression and doubles it into a 24 bar progression. The D7 chords in measures 2, 6, 14, and 22 serve as harmonic ornamental embellishments and thus do not interfere with the overall function of the 12 (24) bar blues progression. (Since this is a McCartney original, perhaps Paul learned the trick from Berry Gordy Junior and Janie Bradford, who wrote [13c] "Money (That's What I Want)" or from Chuck Berry, who wrote [14b] "Roll Over Beethoven".) This is in contrast to the use of the same chord when it is heard in measures 9-12 and 19-20, which do function as integral components of the blues progression. "She's a Woman" also employs a dominant in the final measure (just like [9c] "Boys", [9d] "Chains", [13c] "Money (That's What I Want)", [17] "Little Child", [24] "You Can't Do That", [29b] "Long Tall Sally", and [31b] "Matchbox") [44b] "Kansas City/Hey Hey Hey Hey" (1964 in UK, 1965 in US) G major G G G G7 C C G G D C G G (D) This one is about as standard as a progression can get. The only two things I can mention are the use of a seventh in the 4th bar (to heighten the pull towards C in the 5th bar), and once again the band uses a dominant chord (in this case D) in the final bar (although this time only for the second half of that final bar) to heighten the pull towards the beginning of a repetition of the progression. [46b] "Everybody's Trying to Be My Baby" (1964) E major E E E E A A E E B7 A E E This one, too, is about as standard as a progression can get. The only thing I can mention is the use of a seventh in the 9th bar, which provides more harmonic dissonance and thus tension to the chords. [46c] "Rock and Roll Music" (1964) A major A7 A7 A7 A7 D7 D7 A7 A7 E7 E7 E7 A7 E7 A7 "Rock and Roll Music" extends the 12 bar blues to a 14 bar blues by repeating the last two measures. [56b] "Dizzy Miss Lizzy" (1965) A major A A A A D D A A E7 D A E7 The only non-standard thing about this one is the use of a dominant chord in the final bar (non-standard, that is, for those other than the Beatles - this is now the 10th of 15 Beatles tracks that use the 12 bar blues to do so, making the deviation actually more common than the standard). [56c] "Bad Boy" (1965 in US, 1966 in UK) C major C7 C7 C7 C7 C7 C7 C7 C7 F7 F7 F7 F7 C7 C7 C7 C7 G7 F7 C7 G7 "Bad Boy" pulls the same trick found in [32b] "Slow Down" and [44] "She's a Woman" in that the first 8 bars of the 12 bar blues have been doubled in length, but retain their proportions. Unlike "Slow Down" and "She's a Woman", however, the final 4 bars of "Bad Boy" are not augmented. This makes a unique (at least in the Beatles' recorded and released output up to this point in history) 20 bar blues progression. The final chord, once again, is a dominant. [58] "I'm Down" (1965) G major G G G G C C G G C C D7 G D7 G Perhaps following the example of [46c] "Rock and Roll Music", "I'm Down" turns the 12 bar blues into a 14 bar blues by repeating the final two measures of the pattern. [65] "Day Tripper" (1965) E major E7 E7 E7 E7 A7 A7 E7 E7 F#7 F#7 F#7 F#7 A7 G#7 C#7 B7 "Day Tripper" is a prime example of what I have come to call the Beatles' adolescence (roughly November of 1964 through December of 1965) - a period of just over one year in which their output is split between songs with clear roots in the past ("Everybody's Trying to be my Baby", Dizzy Miss Lizzy", "Run for your Life", et cetera) and songs that begin to push the boundaries and anticipate the band's experimentation and artistic breakthroughs of the later 60's ("You've Got to Hide Your Love Away", "Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)", "In My Life", et cetera). It is as if the band has one foot still firmly in the teeny bopper pop music world and simultaneously the other foot in the more grown-up 'art music' world, just as an adolescent retains aspects from childhood while simultaneously growing into adult life. This can be observed in analyzing "Day Tripper": The first eight measures are identical to the 12 bar blues model (representing the retrospective side), but then the pattern is broken and new and unusual chords - totally and completely unrelated to the 12 bar blues model - are heard (representing the anticipatory, progressive side). Neither F#7 nor G#7 'belong' in E major - much less in an E major 12 bar blues - and yet a listener intuitively feels their propriety. The Beatles are finding their own unique individual solutions to musical problems. They are beginning to distance themselves from the past, taking one of their first steps towards full artistic maturity. "Day Tripper" is one of the first hints at the innovations to come. [74] "The Word" (1965) D major D7 D7 D7 D7 G7 G7 D7 D7 A G D7 D7 This one's about as standard as it can get. [118] "Flying" (1967) C major C C C C F7 F7 C C G7 F C C Fits the mold perfectly. [126] "Don't Pass Me By" (1968) C major C C F F C C G G F F C C Uses the same chords as the mold, in the same order, over the same duration, but with different proportions. [139] "Yer Blues" (1968) E major E E A7 E G,B7 E,A,E,B7 Where [56c] "Bad Boy", [32b] "Slow Down", and [44] "She's a Woman" maintained the proportions of the 12 bar blues but doubled its length (24 instead of 12), "Yer Blues" likewise maintains the proportions but halves its length (6 instead of 12). The last two bars both use more than one chord. The last chord is once again a dominant. [146] "Birthday" (1968) A major A7 A7 A7 A7 D7 D7 A7 A7 E7 E7 A7 A7 The only difference between this and the template is the 10th chord (which is E when it 'should' be D). [155] "Why Don't We Do It In The Road" (1968) D major D7 D7 D7 D7 G7 G7 D7 D7 A7 G7 D7 D7 Standard. [163] "For You Blue" (1970) D major D7 G7 D7 D7 G7 G7 D7 D7 A7 G7 D7 A7 The second chord is a G (instead of D), but this is ornamental and does not effect the function of the 12 bar blues pattern ( a la [13c] "Money (That's What I Want)", [14b] "Roll Over Beethoven", and [44] "She's a Woman"). Last chord is once again a dominant. [166] "The One After 909" (1970) B major B7 B7 B7 B7 B7 B7 B7 B7 B7 B7 E7 E7 B7 F#7 B7 B7 Uses the same chords as a 12 bar blues and nearly in the same order, but it's stretched to 16 bars in duration and is missing an E before the final B. The proportions are not the same as the model. This one does not use a dominant as a final chord. [168] "The Ballad of John and Yoko" (1969) E major E E E E E7 E7 E7 E7 A A E E B7 B7 E E Just like "909", "The Ballad of John and Yoko" stretches the 12 bar blues into a 16 bar blues by doubling the first four measures. It uses the same three chords in nearly the same order (it's missing an A before the final E). CONCLUSIONS

1964: 9 1965: 6 1966: 0 1967: 1 1968: 4 1969: 1 1970: 2

|

Beatles BlogThis blog is a workshop for developing my analyses of The Beatles' music. Categories

All

Archives

May 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed