|

It Won't Be Long

All I've Got to Do

All My Loving

Don't Bother Me

Little Child

Till There Was You

Please Mister Postman

Roll Over Beethoven

Hold Me Tight

You've Really Got a Hold on Me

I Wanna Be Your Man

Devil in Her Heart

Not a Second Time

Money (That's What I Want)

0 Comments

Yesterday I posted a structural analysis of "When I'm Sixty-Four" that gave me the idea of comparing how Ludwig van Beethoven treated his development sections with how the Beatles treated their middle 8 sections. I suspect that in both, observing and analyzing these specific formal components can serve as a microcosm for their development as creative artists as a whole. With that nascent notion in mind, this post will analyze the structural weight of the middle 8 in each Beatles song released prior to August 1964.

[1] "Love Me Do"The middle 8 appears just one time, lasting 8 measures and 14 seconds (10.1% of the song's duration). [2] "P. S. I Love You" The middle 8 appears twice, lasting 8 measures and 14 or 15 seconds each time. In addition, the introduction is based on the middle 8. Adding the introduction to the two iterations of the middle 8, the middle 8 comprises 35.5% (43 of 121 seconds) of the song's duration. This is significantly more formal weight than in "Love Me Do". [3] "Please Please Me" The middle 8 appears just once, lasting 10 measures (the last two of which are transitional, leading back to the verse) and 17 seconds (14.5% of the song's duration). [4] "Ask Me Why" The middle 8 appears twice, lasting 8 measures and 14 seconds both times, totaling 19.4% (28/144) of the song's duration. [5] "There's a Place" The middle 8 appears just once, lasting 10 measures (including a 2 measure transition at the end, which leads back to the verse) and 17 seconds (15.7% of the song's duration). [6] "I Saw Her Standing There" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 10 measures and 14 or 15 seconds each time, totaling 17.0% (29/171) of the song's duration. [6b] "A Taste of Honey" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 6 measures and 13 seconds the first time and 10 seconds the second time (in which it is slightly abbreviated because part way through it jumps to the coda), totaling 19.2% (23/120) of the song's duration. This is the first instance of a middle 8 changing time signatures (from triple to quadruple). It is also, however, not an original song, and thus does not accurately portray the Beatles' own compositional decisions. [7] "Do You Want to Know a Secret" The middle 8 is used just once, lasting 6 measures, and 12 seconds (10.4% of the song's duration). [8] "Misery" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 8 measures and 14 seconds each time, totaling 26.7% (28/105) of the song's duration. [9] "Hold Me Tight" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 7 measures and 12 seconds each time, totaling 16.0% (24/150) of the song's duration. [9b] "Anna (Go To Him)" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 16 measures and 34 or 35 seconds each time, totaling 39.9% (69/173) of the song's duration. These middle 8s are given significantly more structural weight than any other Beatles track recorded so far with the exception of "P. S. I Love You". However, "Anna" is not an original song, and thus does not accurately portray the Beatles' own compositional decisions. [9c] "Boys" This is the first instance of a Beatles song that does not use a middle 8. However, "Boys" is not an original song, and thus does not accurately portray the Beatles' own compositional decisions. [9d] "Chains" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 8 measures and 15 seconds each time, totaling 21.0% (30/143) of the song's duration. However, "Chains" is not an original song, and thus does not accurately portray the Beatles' own compositional decisions. [9e] "Baby It's You" "Baby It's You" does not use a middle 8. However, it is also not an original song, and thus does not accurately portray the Beatles' own compositional decisions. [9f] "Twist and Shout" "Twist and Shout" does not use a middle 8. However, it is also not an original song, and thus does not accurately portray the Beatles' own compositional decisions. [10] "From Me To You" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 8 measures and 14 seconds each time, totaling 24.1% (28/116) of the song's duration. [11] "Thank You Girl" The middle 8 is used just once, lasting 12 measures and 14 seconds, totaling 11.4% (14/123) of the song's duration. [12] "She Loves You" "She Loves You" does not use a middle 8. This is the first such instance found in a Beatles original. [13] "I'll Get You" The middle 8 is used once, lasting 8 measures and 13 seconds, totaling 10.3% (13/126) of the song's duration. [13b] "You Really Got a Hold on Me" The middle 8 appears twice, lasting 5 measures (including one measure of transition back to the verse) and 15 seconds each, totaling 16.7% (30/180) of the song's duration. However, it is also not an original song, and thus does not accurately portray the Beatles' own compositional decisions. [13c] "Money (That's What I Want)" "Money" does not use a middle 8. However, it is also not an original song, and thus does not accurately portray the Beatles' own compositional decisions. [13d] "Devil in her Heart" The middle 8 is used three times (the most so far), lasting 9 measures (including one measure of transition) and 18 seconds each time, totaling 37.2% (54/145) of the song's duration. However, it is also not an original song, and thus does not accurately portray the Beatles' own compositional decisions. [13e] "Till There Was You" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 8 measures and 15 or 16 seconds each time, totaling 23.5% (31/132) of the song's duration. However, it is also not an original song, and thus does not accurately portray the Beatles' own compositional decisions. [13f] "Please Mr. Postman" "Postman" does not use a middle 8. However, it is also not an original song, and thus does not accurately portray the Beatles' own compositional decisions. [14] "It Won't Be Long" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 8 measures and 14 or 15 seconds each time, totaling 22.1% (29/131) of the song's duration. [14b] "Roll Over Beethoven" The middle 8 is used once, lasting 12 measures and 12 seconds, totaling 7.4% (12/163) of the song's duration. This is the least of any Beatles recording that uses a middle 8; however, it is also not an original song, and thus does not accurately portray the Beatles' own compositional decisions. [15] "All My Loving" "All My Loving" is the second Beatles original not to use a middle 8 (the previous being [12] "She Loves You"). [16] "I Wanna Be Your Man" "I Wanna Be Your Man" is the third Beatles original not to use a middle 8 (the previous being [12] "She Loves You", and [15] "All My Loving"). [17] "Little Child" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 6 measures and 10 or 11 seconds each time, totaling 20.8% (21/101) of the song's duration. [18] "All I've Got To Do" The middle 8 is used twice, the first iteration lasting 9 measures (the last of which is a transition) and 17 seconds the first time, and the second iteration lasting 11 measures (including an extension, which propels the song to its coda) and 21 seconds. These total 25.0% (30/120) of the song's duration. [19] "Not a Second Time" "Not a Second Time" is the fourth Beatles original not to use a middle 8 (the previous being [12] "She Loves You", [15] "All My Loving", and [16] "I Wanna Be Your Man"). [20] "Don't Bother Me" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 16 measures and 22 seconds each time, totaling 30.1% (44/146) of the song's duration. [21] "I Want to Hold Your Hand" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 11 measures and 20 or 21 seconds each time. Additionally, for the second time (behind [2] "P. S. I Love You"), the introduction is based on the middle 8, lasting 4 measures and 7 seconds. Combining the intro and two middle 8s, that music accounts for 33.1% (48/145) of the song's duration. [22] "This Boy" The middle 8 is used once, lasting 8 measures and 26 seconds, totaling 19.3% (26/135) of the song's duration. [23] "Can't Buy Me Love" "Can't Buy Me Love" is the fifth Beatles original not to use a middle 8 (the previous being [12] "She Loves You", [15] "All My Loving", [16] "I Wanna Be Your Man", and [19] "Not a Second Time"). [24] "You Can't Do That" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 8 measures and 15 second each time, totaling 19.6% (30/153) of the song's duration. [25] "And I Love Her" The middle 8 is used once, lasting 8 measures and 18 seconds, constituting 12.2% (18/148) of the song's duration. [26] "I Should Have Known Better" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 16 measures and about 29 seconds both times, totaling 36.0% (58/161) of the song's duration. [27] "Tell Me Why" The middle 8 is used just once, lasting 10 measures and 15 seconds,constituting 11.7% (15/128) of the song's duration. [28] "If I Fell" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 5 measures and 11 seconds each, totaling 15.9% (22/138) of the song's duration. [29] "I'm Happy Just To Dance With You" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 4 measures and 7 seconds each time, totaling 12.1% (14/116) of the song's duration. [29b] "Long Tall Sally" "Long Tall Sally" does not employ a middle 8; however, it is also not an original song, and thus does not accurately portray the Beatles' own compositional decisions. [30] "I Call Your Name" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 8 measures and 16 or 15 seconds each, totaling 24.1% (31/128) of the song's duration. The middle 8 is particularly interesting in this number because it replaces the first half of verses 2 and 3. It retains its function as a harmonically contrasting section with the verse, but is always followed in both instances not by a whole verse, but only by the second half of a verse. Unusual. [31] "A Hard Day's Night" The middle 8 appears twice, lasting 8 measures and 14 seconds each time, totaling 18.3% (28/153) of the song's duration. [31b] "Matchbox" "Matchbox" does not employ a middle 8; however, it is also not an original song, and thus does not accurately portray the Beatles' own compositional decisions. [32] "I'll Cry Instead" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 8 measures and 10 seconds each time, totaling 19.0% (20/105) of the song's duration. [32b] "Slow Down" "Slow Down" does not employ a middle 8; however, it is also not an original song, and thus does not accurately portray the Beatles' own compositional decisions. [33] "I'll Be Back" "I'll Be Back" is the first Beatles song to date using two different middle 8s. They both serve the same basic function of contrasting with the verses (which is why I classify them both as middle 8s), but they are distinctly different from each other, with only the endings bearing any resemblance. The first middle 8 is used twice, lasting 6.5 measures (the seventh is a 2/4 bar, while the rest of the song is in common time) and 12 or 13 seconds. The second middle 8 is used once, lasting 9.5 measures (again, the final bar is a 2/4) and 18 seconds. Combine the two middle 8s together, and they total 30.5% (43/141) of the song's duration. While 30.5% is not the greatest proportion so far, the fact that two different middle 8s are used in "I'll Be Back" illustrates a significant increase in structural weight given to the middle 8. [34] "Any Time At All" "Any Time At All" is the sixth Beatles original not to use a middle 8 (the previous being [12] "She Loves You", [15] "All My Loving", [16] "I Wanna Be Your Man", [19] "Not a Second Time", and [23] "Can't Buy Me Love"). [35] "Things We Said Today" The middle 8 is used twice, lasting 8 measures and 16 seconds both times, totaling 20.8% (32/154) of the song's duration. Furthermore, the song is in A minor, however in both iterations of the middle 8, that switches to the parallel major. In other words, the middle 8s are emphasized (i.e. given more structural weight) by changing the tonality from A minor to A major. [36] "When I Get Home" The middle 8 is used once, lasting 10 measures and 21 seconds, constituting 15.6% (21/135) of the song's duration. Conclusions All of this data might be more easily observable in this chart. Of the Beatles first 36 original songs, 30 employ at least one middle 8. Clearly, the Beatles as composers value the structural benefits of a section that contrasts harmonically with the verses. That being said, at this early stage in their career, the middle 8 comprises only about 20% of the song (give or take 10%). Every song, of course, needs something to contrast the verses, otherwise the song would be quite monotonous. The six tunes that do not employ a middle 8 feature a chorus that serves this contrasting function. Of these six, two ([15] "All My Loving" and [19] "Not a Second Time") blur the line between middle 8 and chorus - they could be interpreted either way. The next step is to do a similar analysis of the middle 8s in subsequent Beatles songs and then compare and contrast with the ones analyzed above. On 27 December 1963, The [London] Times published a now-famous article titled "What Songs the Beatles Sang", with the byline "From our music critic", presumed to William Mann. In his article (the full text of which may found here), Mann wrote, "one gets the impression that they think simultaneously of harmony and melody, so firmly are the major tonic sevenths and ninths built into their tunes, and the flat submediant key switches, so natural is the Aeolian cadence at the end of Not A Second Time (the chord progression which ends Mahler's Song of the Earth)." As a well-educated musician, I am both intrigued and confused by Mann's words. While I know what the terms "aeolian" and "cadence" mean separately, I have never previously encountered them used together. In his book A Hard Day's Write: The Stories Behind Every Beatles Song, Steve Turner is equally perplexed: "An 'aeolian cadence' is not a recognised musical description and generations of music critics have puzzled over exactly what Mann was referring to" (page 40). A quick Google search of the term "aeolian cadence" produces two basic types of results: first, those quoting Mann's article; second, those asking what Mann's article means. (Try it and you'll see.) This blog, then, will weigh the evidence in an attempt to discover precisely what he meant. The term "aeolian" refers to a specific type of scale consisting of the following interval pattern: W H W W H W W (where W = whole step, H= half step). This is the same pattern as the natural minor scale, and may also be described as the notes A to A on the piano if you play only the white keys. The term "cadence" refers to a concluding musical gesture, and cadences are usually found at the end of structural sections, or at the end of a song. Quoting a very popular and widely-used harmony textbook, "We use the term cadence to mean a harmonic goal, specifically the chords used at the goal" (Kostka/Payne, page 152). If the goal is reached at the end of a song, there is no reason to conclude by fade out. On the other hand, that sense of harmonic conclusion may be obfuscated by a fade out instead of a cadence. Though I suppose it is possible for a song to use both a concluding cadence and a fade out, I do not believe I have ever heard a song that actually does so. It would, after all, be redundant since both cadences and fade outs are concluding gestures. "Not a Second Time", however, is in G major (not aeolian) and uses a fade out instead of a cadence for its conclusion; so what exactly Mann was referring to by "Aeolian cadence at the end of Not A Second Time" is uncertain. My best guess is that the last several seconds of the song feature just two chords: G major and E minor, and the G major scale (G-A-B-C-D-E-F#-G) and the E aeolian (from which the chord E minor can be extracted) scale (E-F#-G-A-B-C-D-E) share identical notes, they just start on different pitches, making these two tonalities very closely related. I wonder if Mann heard this progression and mistakenly identified it as a cadence. Some scholars have concluded otherwise, suggesting Mann was referring instead to the E minor chords that follow D7 chords at the end of the Middle 8s: Am Bm D7 Em You hurt me then, You're back again. No, no, no, not a second time. Personally, I find this explanation less satisfying than the one above because (1) it's not "at the end" of the song, as the article specifies (though perhaps the article meant "at the end of the Middle 8"?); and (2) this pattern is known - as it was in 1963 - as a deceptive cadence, in which the fifth scale degree (in this case D7) resolves not to the first scale degree (G) as a listener might expect, but rather to the sixth (E minor). But Dominic Pedler, in his book The Songwriting Secrets of the Beatles, addresses that concern head-on: "Mann would argue that it is not the same thing as a "V-vi" Interrupted or Deceptive cadence because - at that precise point in the song - the role of the E minor as a "vi" is being questioned and is veering towards tonic status" (page 137). Yet this is uncertain: Typically a B7 would be needed to justify E minor as "tonic status", and the chord used in the song is a Bm - not a B7. This subtle but significant difference implies that E minor is not tonic, and thus this progression is a deceptive cadence. Or maybe that's precisely why Mann referred to this as an aeolian cadence and not a deceptive cadence - because if the song is in E aeolian, B would be minor (since D is natural, not sharp). Basically it comes down to opinion: How do you hear this passage - with G as tonic, or with E as tonic? Am Bm D7 Em You hurt me then, You're back again. No, no, no, not a second time. G major: ii iii V7 vi E aeolian: iv v bVII7 i Both are unusual, and evidence can be presented in favor of both, but I have to say I hear G as tonic, making this a deceptive cadence - particularly when looking on a slightly larger scale. Here are the lyrics and chords immediately preceding the passage in question: Am7 Bm7 G Em You're giving me the same old line. I'm wondering why. In this instance, G is quite clearly tonic. This firm tonal grounding and the use of very similar chords immediately following lends credence to calling the original progression a deceptive cadence and not an aeolian cadence. Another option: Perhaps Mann simply got his vocab terms confused and really meant "deceptive cadence" when he wrote "aeolian cadence". While this interpretation solves the problem of a lack of cadence, the issue over "at the end" remains. At the end... of what? If it's the end of the Middle 8, then problem solved; but if it's at the end of the song, we are still left with uncertainty. Mann provides another clue when he claims that the same chord progression concludes Gustav Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth), but simple observation proves otherwise. Below is a reduction of the last 10 measures of Das Lied (click to enlarge in a new window). This example shows a C9 chord (though the root is absent from these measures, it is heard shortly beforehand and a listener would have no problem retaining that tonality in their mind's ear) resolving to a C6 chord at marker 69. That C6 chord is the harmony that concludes the piece. By contrast, "Not a Second Time" concludes by fading out over alternating G and Em chords. While not entirely unrelated (both make use of the sixth scale degree), the degree of relation is far removed. Thus, the claim that "Not a Second Time" and Das Lied end with the same progression is irrefutably false. It would, in fact, be far more accurate to compare the ending of the Mahler to the ending of "She Loves You" (which was released four months prior to Mann's article) , which also ends with an added sixth chord. However, Mann has clearly shown that the word "end" is open to great interpretation. If, as was suggested early, Mann meant to refer to the cadence "at the end [of the middle 8]", then perhaps his use of the term "end" is similarly flexible regarding the Mahler: Perhaps the cadence is in the final movement of Das Lied, not at the very end but perhaps at the end of a particular section; yet listening to the entire 6th movement of Das Lied yields no such cadence. In fact, much of Mahler's later work (such as Das Lied and the 9th and 10th Symphonies) "follows Wagner's lead in taking tonality closer and closer to the breaking point. Nearly every piece of music before Wagner's time was very clearly in a particular key; Mahler's music, on the other hand, has long stretches that don't seem to be in a key at all" (Pogue, page 61). Cadences are largely dependent on tonality, and without tonality, the impact and effect of cadences are greatly thwarted. Nevertheless, Mahler scholar Constantin Floros found what he believed to be deceptive cadences at rehearsal marker 24-26 of the final movement of Das Lied in his book Gustav Mahler: The Symphonies (page 267-68), illustrated as a piano reduction below (click to enlarge): Personally, I don't hear these as cadences. Modulations, certainly, but the tonal expectation that characterizes cadences (and especially deceptive cadences) is greatly lacking in this excerpt - to the point where I cannot justify the label of cadence of any kind, much less deceptive cadence.

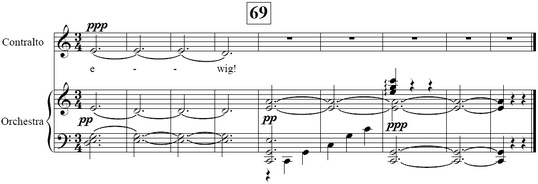

Even if these were explicitly clear deceptive cadences, they are not very similar to the progression in "Not a Second Time". In each of the three potential cadences in the Mahler, the bass ascends by half step (B-flat to C-flat, G to A-flat, and F to F-sharp), while the Beatles' cadence ascends by whole step (D to E). (Parenthetically, Mahler did use deceptive cadences in his 4th and 5th Symphonies. Maybe Mann was confused and meant to say one of those works instead of Das Lied? That might be too much of a stretch - even for William Mann.) After all of that, I think it's safe to say that regardless of what William Mann really meant, he failed to clearly express his ideas. Even so, Mann's article remains widely cited and quoted because even though Mann's analysis is faulty, it is the first instance of Beatles music being seriously analyzed. Quoted from 1972 in The Beatles Anthology, John Lennon (the song's primary author) said, "I still don't know what it means at the end, but it made us acceptable to the intellectuals. It worked and we were flattered." (page 96). Even so, Lennon could not help but make fun of the article, admitting a "quiet giggle when straight-faced critics start feeding all sorts of hidden meanings into the stuff we write. William Mann wrote the intellectual article about the Beatles. He uses a whole lot of musical terminology and he's a twit" (Anthology, page 96); and in a 1980 interview with David Sheff of Playboy, Lennon (despite mistakenly remembering the article referring to "It Won't Be Long") claimed, "To this day I don't have any idea what [aeolian cadences] are. They sound like exotic birds" (page 87). CITATIONS Beatles. The Beatles Anthology. Chronicle Books, 2000. Floros, Constantin. Gustav Mahler: The Symphonies. Amadeus Press, Portland OR, 1993. Kostka, Stefan and Dorothy Payne. Tonal Harmony. McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1995. Pedler, Dominic. The Songwriting Secrets of the Beatles. Omnibus Press, 2001. Pogue, David and Scott Speck. Classical Music for Dummies. IDG Books Worldwide, Chicago, IL, 1997. Sheff, David. All We Are Saying: The Last Major Interview with John Lennon and Yoko Ono. St. Martin's Griffin, 1981. Turner, Steve. A Hard Day's Write: The Stories Behind Every Beatles Song. itbooks, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, 2005. Deceptive cadences refer to a particular pattern of chords in which the chord built on the fifth scale degree, which usually resolves to the first scale degree, instead proceeds to the sixth scale degree. This may be expressed in roman numerals as follows:

Authentic: V-I Deceptive V-vi (or, less commonly, V-bVI) One of the defining characteristics of a deceptive cadence is the aural anticipation of tonic following the dominant chord. That expectation is then thwarted, thus the term "deceptive". Additionally, cadences by definition conclude phrases. Deceptive cadences, then, may only be found at the ends of phrases. Many Beatles songs ([5] "There's a Place", [11] "Thank You Girl", [12] "She Loves You", [25] "And I Love Her", [34] "Any Time At All", [40] "I Don't Want to Spoil the Party", [47] "Ticket to Ride", [50] "Yes It Is", [52] "You Like Me Too Much", [64] "Drive My Car", [68] "We Can Work it Out", [70] "I'm Looking Through You", [96] "A Day in the Life", [106] "She's Leaving Home", [144] "Glass Onion" [154] "The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill", [170] "Something", [174] "Her Majesty", and [185] "Because") use the same chords that would be used in a deceptive cadence, but these are not actually so because they bridge phrases (with V concluding the former phrase and vi starting the new phrase) rather than conclude them (with V-vi concluding the former phrase and the new phrase beginning on some other chord). Conversely, some songs ([21] "I Want to Hold Your Hand", [26] "I Should Have Known Better", [27] "Tell Me Why", [29] "I'm Happy Just To Dance With You", [32] "I'll Cry Instead", [51] "The Night Before", [67] "In My Life", [87] "For No One", [93] "Strawberry Fields Forever", [94] "When I'm Sixty-Four", [107] "With a Little Help From My Friends", [114] "All You Need Is Love", [120] "Hello Goodbye", [147] "Piggies", [153] "I'm So Tired", [164] "Let It Be", [171] "Oh! Darling", [183] "Polythene Pam") use the right chords in the middle of their progression - rather than at the end as part of a cadence. More unusually, [43] "Eight Days a Week" uses the same chords not as V to vi, but as bVII to i during a tonicization of the relative minor during the Middle 8; and [181] "Sun King" uses the chords, but in a non-functional harmonic context. All of these instances are not examples of deceptive cadences and are thus purposely omitted from the list below. With those out of the way, 7 Beatles songs actually do employ true deceptive cadences, and each is identified below with analysis and explanation. [2] "P. S. I Love You" uses probably the most blatant of all the Beatles' deceptive cadences a total of four times (0:25, 0:43, 1:15, 1:47), each iteration using the same lyrics and chords. A Bb C D P. S. I love you, you, you, you. V bVI bVII I Deceptive cadences, as their name implies, are deceiving by nature. But this particular deceptive cadence draws further attention to itself by proceeding from V to bVI - a strikingly foreign chord in D major. In a textbook example of a deceptive cadence, the insertion of this bVI extends the phrase (from what would have been 8 bars to 10) and delays the eventual resolution to I. [7] "Do You Want to Know a Secret" uses the five iterations of the same deceptive cadence: 0:38, 1:05, 1:43, 1:47, 1:51 - the first three of which come at the end of each verse; the last two coming in quick succession as part of the song's coda, which fades out as the cadence repeats. F#m B7 A B7 C#m Say the words you long to hear: I'm in love with you. ii V7 IV V7 vi This deceptive cadence also extends the phrase and delays tonic by two measures. [19] "Not a Second Time" uses a total of three deceptive cadences (0:41, 1:01, 1:47), the first and last of which are to identical lyrics sung by Lennon . . . Am Bm D7 Em You hurt me then, You're back again, No no no, Not a second time. ii iii V7 vi . . . while the middle cadence is during the solo, which employs the same melody and chords as the outer deceptive cadences, just played by a piano instead of sung by Lennon. In all three instances, the deceptive cadences replace resolution to tonic (rather than delay resolution to tonic, as was the case with "P. S. I Love You" and "Do You Want to Know a Secret".) [36] "When I Get Home" is the jackpot for Beatles songs that use deceptive cadences. With a total of nine iterations of four unique progressions, it uses more deceptive cadences than any other Beatles tune. The first (the most frequent with four occurring at 0:12, 0:42, 1:13, and 1:47) appears near the conclusion of each chorus with identical lyrics and chords each time. D7 G7 Am I got a whole lot of things to tell her when I get home II7 V7 vi The next-most-frequent, with three instances occurring at 0:31, 1:01, and 1:51, appears near the end of each verse, with identical chords but different lyrics each time. C F7 G7 A I've got a whole lot of things I've got to say to her. Woah-oh-oh-ah I've got a girl who's waiting home for me tonight. Woah-oh-oh-ah. I've got no business being here with you this way. Woah-oh-oh-ah. I IV7 V7 VI These deceptive cadences vary slightly from the previous examples (from the same song) because while they both feature G7 (V7) chords followed by chords based on A, the former uses A minor while the latter uses A major. The last two instances are both unique in the song. At 1:32, near the end of the Middle 8: F G7 Am till I walk out that door again. IV V7 vi The final deceptive cadence, occurring at 2:02, is identical to those four occurring at 0:12, 0:42, 1:13, and 1:47 except for the final chord, which is major instead of minor. In this way, this cadence may be viewed as a combination of the previously heard deceptive cadences, with the purpose to propelling the song to its conclusion. D7 G7 A I got a whole lot of things to tell her when I get home II7 V7 VI In all nine instances of deceptive cadences in "When I Get Home", the deceptive cadence expands the phrase and delays the resolution of tonic. [131] "Ob-La-Di Ob-La-Da" uses just one deceptive cadence (2:58) but it's also one of the more obvious in the Beatles repertoire because by the time we hear the deceptive cadence, we have already heard it as an authentic cadence (V to I) 3 times (0:42, 1:16, 2:07). In explicit and definitive terms, then, this deceptive cadence serves to prolong the phrase and delay the resolution to tonic. Bb Dm/F Gm7 Bb F7 Gm Ob-la-di Ob-la-da Life goes on bra, La la how the life goes on. I iii/5 vi7 I V7 vi In [145] "I Will", all four deceptive cadences are saved for the end of the song. The final verse substitutes vi for I three times (1:11, 1:15, and 1:20), prolonging the phrase and delaying tonic resolution - but not before the really attention-grabbing deceptive cadence at 1:25, which pulls the same stunt (V to bVI) McCartney used way back in "P. S. I Love You". Bb C7 Dm Bb F (Fdim Gm C7 Db7) Sing it loud so I can hear you Make it easy to be near you For the things you do endear you to me and you know I will IV V7 vi IV I i* ii V7 bVI [172] "Octopus's Garden", just like "I Will", saves both of its deceptive cadences for the coda (2:34, and 2:39). A B C#m A B C#m In an octopus's garden with you. In an octopus's garden with you. IV V vi IV V vi Both of these deceptive cadences prolong the final verse, propelling the son to its conclusion, and delay resolution of tonic. OBSERVATIONS & CONCLUSIONS:

1963: 2 ([7] "Do You Want to Know a Secret", [19] "Not a Second Time") 1964: 1 ([36] "When I Get Home") 1965: 0 1966: 0 1967: 0 1968: 2 ([131] "Ob-La-Di Ob-La-Da", [145] "I Will") 1969: 1 ([172] "Octopus's Garden") Continuing my index of formal structural analyses begun in my Dec 5 post, this one will continue the series by looking at the album With the Beatles. For my loose definitions of structural terms, please review my post from Dec. 5.

FORMAL STRUCTURE OF SONGS ON WITH THE BEATLES Song Title Section Timing "It Won't Be Long" Chorus 0:00-0:15 Verse 1 0:15-0:28 Chorus 0:28-0:42 Middle 8 0:42-0:56 Verse 2 0:56-1:09 Chorus 1:09-1:23 Middle 8 1:23-1:38 Verse 3 1:38-1:51 Chorus 1:51-2:00 Coda (independent) 2:00-2:11 Comments: On Please Please Me, every single song had an introduction. The very first track on With the Beatles breaks the pattern: instead of an intro, the song launches straight into the chorus. The coda uses material entirely independent from the rest of the song. "All I've Got To Do" Intro (independent) 0:00-0:03* Verse 1 0:03-0:15 Chorus 0:15-0:25 Verse 2 0:25-0:38 Chorus 0:38-0:48 Middle 8 0:48-1:05 Verse 3 1:05-1:18 Chorus 1:18-1:28 Middle 8 1:28-1:49 Coda (verse) 1:49-2:00 Comments: Intro is a single guitar chord (E aug 9,11) that has no relation to anything that comes after it. Chorus uses different lyrics. Second Middle 8 features an extension (it's longer the second time than it was the first), which I've not noticed in a Beatles tune up until this point. Verses 2 and 3 share identical lyrics. "All My Loving" Verse 1 0:00-0:25 Verse 2 0:25-0:50 Middle 8 0:50-1:02 Solo 1:02-1:15 Verse 3 1:15-1:40 Middle 8 1:40-1:52 Coda (m8) 1:52-2:06 Comments: No introduction, just starts right in with Verse 1. Verses 1 and 3 share identical lyrics. Just like "Not a Second Time", "All My Loving" blurs the line between middle 8 and chorus. "Don't Bother Me" Intro (verse/independent) 0:00-0:05 Verse 1 0:05-0:17 Chorus 0:17-0:22 Verse 2 0:22-0:34 Chorus 0:34-0:40 Middle 8 0:40-1:02 Verse 3 1:02-1:13 Chorus 1:13-1:19 Solo 1:19-1:30 Chorus 1:30-1:36 Middle 8 1:36-1:58 Verse 4 1:58-2:09 Chorus/Coda 2:09-2:26 Comments: The introduction is similar to the verses, but the motive played by the bass and guitar never appears again, nor does the chord progression. This is probably the shortest chorus so far in a Beatles song. It is also probably the longest Middle 8 of any Beatles song so far. It's also interesting to note that the lyrics in the choruses, while very similar, are not identical. Verses 3 and 4 share identical lyrics. "Little Child" Intro (verse) 0:00-0:06* Verse/Chorus 0:06-0:19 Verse/Chorus 0:19-0:31 Middle 8 0:31-0:41 Verse/Chorus 0:41-0:54 Solo 0:54-1:12 Middle 8 1:12-1:23 Verse/Chorus 1:23-1:34 Coda (chorus?) 1:34-1:44* Comments: Two-part introduction: first the harmonica riff, second the backing. Both stem from the verses. A la "Love Me Do", the utter simplicity of "Little Child" actually makes its structure somewhat ambiguous. Every verse features identical lyrics, which blurs the boundaries delineating where the verse ends and the chorus starts. For that reason, I've labeled these sections verse/chorus. If the song does feature a chorus, the coda makes use of it. Since song titles often come from the lyrics of the chorus, this tune might have easily been called "Baby take a Chance With Me". "Till There Was You" Intro (verse) 0:00-0:08 Verse 1 0:08-0:23 Verse 2 0:23-0:39 Middle 8 0:39-0:54 Verse 3 0:54-1:10 Solo 1:10-1:26 Middle 8 1:26-1:42 Verse 4 1:42-1:58 Coda 1:58-2:12* Comments: No chorus, although the line "Till there was you" could be interpreted as such since those are the only lyrics that remain the same from verse to verse. The lack of increased energy, however, prompts me to instead categorize it as part of the verse. The coda draws out the same words, so it could be interpreted as being based on the chorus (if there is one). Otherwise it could be based on the verse. On the other hand, despite the lyrical similarities, the music is largely unrelated to the rest of the song, so it could also been interpreted as independent. "Please Mister Postman" Intro (bridge) 0:00-0:08 Chorus 0:08-0:23 Verse 1 0:23-0:39 Bridge 0:39-0:54 Chorus 0:54-1:10 Verse 2 1:10-1:26 Chorus 1:26-1:42 Coda 1:42-2:31* Comments: Intro based on bridge, which naturally leads to chorus. Bridge sounds very similar to verse. Part of the reason why is that the same chord progression (A, F-sharp minor, D, E) permeates the entire song (whereas bridges will often change the chords slightly to propel the music towards the chorus). Lastly, this song has the longest, most developed coda (three sections, which share the same chord progression as the rest of the song but is otherwise independent) in Beatles recordings to date - even bigger than "Twist and Shout" from earlier that same year, though certainly nowhere near the size and substance of "Hey Jude" five years later. "Roll Over Beethoven" Intro 0:00-0:17 Verse 1 0:17-0:29 Chorus 0:29-0:35 Verse 2 0:35-0:47 Chorus 0:47-0:54 Verse 3 0:54-1:05 Chorus 1:05-1:11 Middle 8 1:11-1:23 Chorus 1:23-1:29 Solo 1:29-1:47 Verse 4 1:47-1:58 Chorus 1:58-2:04 Verse 5 2:04-2:22 (Chorus 2:16-2:22)* Chorus/Coda 2:22-2:43 Comments: Another "split intro" (where the introduction can be divided into two distinct parts): first the guitar lick, then the backing is added. The former will reappear in the solo, the latter is used in the verses. Three verses before middle 8 (usually it's two). More verses (five) than any other Beatles recording to date (several on Please Please Me use four). The chorus always use similar lyrics ("Roll over Beethoven...") each time except for the chorus following Verse 5, which instead substitutes "Long as she's got a dime the music will never stop". (This might is likely because the coda, which immediately follows, is based on the chorus.) Since the energy levels of the verse and chorus are equal, I would have considered them part of the same section (rather than splitting them into two distinct sections) had the lyrics of the chorus different each time. That is what happens in Verse 5, so to indicate that in the above chart, I've included 2:16-2:22 twice: as part of Verse 5, and also as part of the subsequent chorus. "Hold Me Tight" Intro (verse) 0:00-0:03 Verse 1 0:03-0:17 Bridge 0:17-0:24 Chorus 0:24-0:31 Verse 2 0:31-0:45 Bridge 0:45-0:52 Chorus 0:52-1:00 Middle 8 1:00-1:12 Verse 3 1:12-1:26 Bridge 1:26-1:33 Chorus 1:33-1:40 Middle 8 1:40-1:52 Verse 4 1:52-2:07 Bridge 2:07-2:14 Chorus 2:14-2:21 Coda (chorus) 2:21-2:30 Comments: Structurally speaking the busiest Beatles recording so far. Verse 1 and 3 share lyrics, as do verses 2 and 4. "You've Really Got A Hold On Me" Intro (chorus) 0:00-0:13 Verse 1 0:13-0:35 Chorus 0:35-0:47 Verse 2 0:47-1:09 Chorus 1:09-1:22 Middle 8 1:22-1:37 Transition 1:37-1:49 Verse 3 1:49-2:11 Chorus 2:11-2:24 Middle 8 2:24-2:39 Coda (chorus) 2:39-3:00 Comments: Intro and Coda based on chorus. "I Wanna Be Your Man" Intro (verse) 0:00-0:01 Verse 1 0:01-0:21 Chorus 0:21-0:31 Verse 2 0:310:51 Chorus 0:51-1:01 Solo 1:01-1:16 Verse 3 1:16-1:35 Chorus 1:35-1:46 Coda (chorus) 1:46-1:58 Comments: very straight forward. The shortest introduction (guitar lick reappears in second verse, right after the line "Love you like no other, baby, like no other can") of any Beatles song to date (of those that use an intro, of course - not all do). "Devil In Her Heart" Intro (verse) 0:00-0:08 Verse 1 0:08-0:24 Middle 8 0:24-0:42 Verse 2 0:42-0:58 Middle 8 0:58-1:16 Verse 3 1:16-1:32 Middle 8 1:32-1:50 Verse 4 1:50-2:05 Coda (verse) 2:05-2:25 Comments: One of the most structurally primitive Beatles recording so far - a verse, and something to contrast that verse (middle 8 - although in this song it's actually nine measures long, not eight), with a beginning and ending (both using the backing from the verses with an overlaid guitar riff) tacked on. No solo, no chorus. "Not A Second Time" Verse 1 0:00-0:13 Verse 2 0:13-0:26 Chorus 0:26-0:45* Solo 0:451:05 Verse 3 1:05-1:18 Verse 4 1:18-1:32 Chorus 1:32-1:51* Coda (chorus) 1:51-2:04* Comments: Verses 1 and 3 same; as are 2 and 4. This one blurs the line between chorus and middle 8: the tonal shifts suggest a middle 8, but the energy is not much different from the verse (middle 8s are often less energetic than the verses - as in "It Won't Be Long" - while choruses are often more energetic - as in "Please Please Me"). Then again the Beatles early recordings have shown quite clearly that their choruses rarely do feature that characteristic increase in energy, which would lend support to calling these sections choruses instead of a middle 8s. Additionally, the title comes from the end of the section in question, which would be unusual for a middle 8, but extremely common for a chorus. For all of those reasons and more, I've opted to label these sections as a chorus. "Money (That's What I Want)" Intro (chorus) 0:00-0:15 Verse 1 0:15-0:22 Chorus 0:22-0:37 Verse2 0:37-0:44 Chorus 0:44-0:59 Verse 3 0:59-1:06 Chorus 1:06-1:21 Solo 1:21-1:36 Verse 4 1:36-1:44 Chorus 1:44-1:59 Coda (chorus) 1:59-2:47 Comments: Very short verses, but one of the longer codas (two sections, based on the chorus) in Beatles recordings so far. Verses 3 and 4 share identical lyrics. GENERAL CONCLUSIONS All 14 tracks of Please Please Me employed both introductions and codas. On With the Beatles, not every song does: "It Won't Be Long" begins with a chorus, and "All My Loving" and "Not a Second Time" begin with a verse. Every song on With the Beatles does, however, use a coda. Two of these codas ("Money (That's What I Want)", and "Please Mr. Postman") are substantial in size. Unlike Please Please Me (in which 6 of the 14 tracks did not use a chorus), all but two on With the Beatles ("All My Loving" and "Devil in her Heart") does use a chorus, though two of them ("Little Child" and "Not a Second Time") blur the distinction between middle 8 and chorus. |

Beatles BlogThis blog is a workshop for developing my analyses of The Beatles' music. Categories

All

Archives

May 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed