|

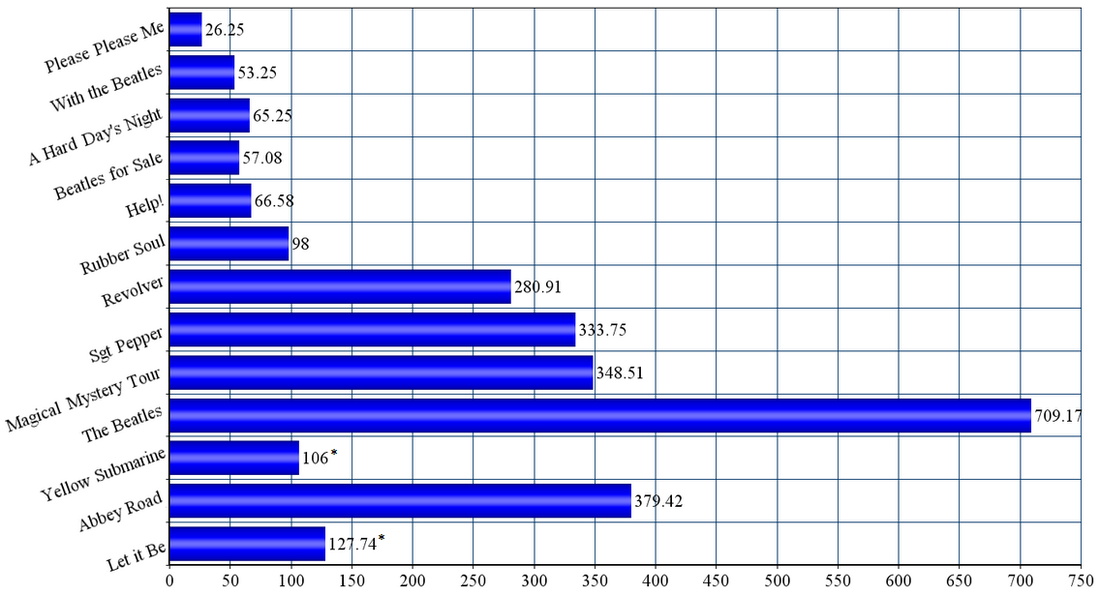

Having completed my study of documented hours spend in the recording studio on each Beatles album, I can now compile my findings to produce a visual illustration: a bar graph comparing total documented studio time per Beatles album. Using this example, it is very clear indeed that The Beatles (a.k.a. The White Album) took the longest time to record by far (about twice as much time as it took the band to record Pepper, Magical Mystery Tour, or Abbey Road). This isn't surprising as The White Album is the only Beatles double album, so it makes sense that it would take about twice as long to record.

Lastly, notice that both Let it Be and Yellow Submarine have asterisks next to their number. This is because documentation for those two albums is incomplete. No doubt both albums took more time than shown (probably about twice those figures), but the number listed is what is documented. Any attempt to estimate precise numbers above those shown would be futile.

0 Comments

Many books purport that Sgt. Pepper took "700 hours of studio time to produce" (Simonelli page 107; see also Julien page 5, Sawyers page 81, Wald page 242, Ingham page uncertain, Sandford page 130, Tomson page 259, Emerick page 190). This figure likely originated with George Martin's book With a Little Help From My Friends: The Making of Sgt. Pepper in which he wrote, "According to Geoff Emerick's calculation, we spent no fewer than 700 hours, or twenty-nine complete days, of our lives working on it in the studio" (page 167). Mark Lewisohn's The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions, however, paints a very different picture. Not including the recordings of "Strawberry Fields Forever" or "Penny Lane", which were originally intended to be on the album but were ultimately left off, here's a catalog of exactly how many hours were spent in the studio creating Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

year.month.day start time - end time = # of hours that day 1966.12.06 6:45pm-1:50am = 7.08 hours 1966.12.08 2:30pm-5:30pm = 3 hours 1966.12.20 7:00pm-1:00am = 6 hours 1966.12.21 7:00pm-10:00pm = 3 hours 1967.01.19 7:30pm-2:30am = 7 hours 1967.01.20 7:00pm-1:10am = 6.17 hours 1967.01.30 7:00pm-8:30pm = 1.5 hours 1967.02.01 7:00pm-2:30am = 7 hours 1967.02.02 7:00pm-1:45am = 6.75 hours 1967.02.03 7:00pm-1:15am = 6.25 hours 1967.02.08 7:00pm-2:15am = 7.25 hours 1967.02.09 unknown 1967.02.10 8:00pm-1:00am = 5 hours 1967.02.13 7:00pm-3:30am = 8.5 hours 1967.02.14 7:00pm-12:30am = 5.5 hours 1967.02.16 7:00pm-1:45am = 6.75 hours 1967.02.17 7:00pm-3:00am = 8 hours 1967.02.20 7:00pm-2:15am = 7.25 hours 1967.02.21 7:00pm-12:45am = 5.75 hours 1967.02.22 7:00pm-3:45am = 8.75 hours 1967.02.23 7:00pm-3:45am = 8.75 hours 1967.02.24 7:00pm-1:15am = 6.25 hours 1967.02.28 7:00pm-3:00am = 8 hours 1967.03.01 7:00pm-2:15am = 7.25 hours 1967.03.02 7:00pm-3:30am = 8.5 hours 1967.03.03 7:00pm-1230am = 5.5 hours 1967.03.06 7:00pm-12:30am = 5.5 hours 1967.03.07 7:00pm-2:30am = 7.5 hours 1967.03.09 7:00pm-3:30am = 8.5 hours 1967.03.10 7:00pm-4:00am = 9 hours 1967.03.13 7:00pm-2:30am = 7.5 hours 1967.03.15 7:00pm-1:30am = 6.5 hours 1967.03.17 7:00pm-12:45am = 5.75 hours 1967.03.20 7:00pm-3:30am = 8.5 hours 1967.03.21 7:00pm-2:45am = 7.75 hours 1967.03.22 7:00pm-2:15am = 7.25 hours 1967.03.23 7:00pm-3:45am = 8.75 hours 1967.03.28 7:00pm-4:45am = 9.75 hours 1967.03.29 7:00pm-5:45am = 10.75 hours 1967.03.30 11:00pm-7:30am = 8.5 hours 1967.03.31 7:00pm-3:00am = 8 hours 1967.04.01 7:00pm-6:00am = 11 hours 1967.04.03 7:00pm-3:00am = 8 hours 1967.04.04 7:00pm-12:45am = 5.75 hours 1967.04.06 7:00pm-1:00am = 6 hours 1967.04.07 7:00pm-1:00am = 6 hours 1967.04.17 7:00pm-10:30pm = 3.5 hours 1967.04.19 7:00pm-12:30am = 5.5 hours 1967.04.20 5:00pm=-6:15pm = 1.25 hours 1967.04.21 7:00pm-1:30am = 6.5 hours This totals 333.75 hours (20,025 minutes). Even accounting for the lack of documentation on February 9, this number is well short of the mythical 700 hours. Even so, 333.75 hours divided by 13 tracks = 25.67 hours of studio time per track - no doubt a greater number than any previously recorded album, Beatles or otherwise. CITATIONS Emerick, Geoff and Howard Massey. Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of the Beatles. Gotham Books, published by Penguin Group (USA) Inc., New York, NY, 2006. Ingham, Chris. The Rough Guide to The Beatles. Penguin Books Ltd, New York, NY, 2006. Julien, Oliver, ed. Sgt. Pepper and the Beatles: It Was Forty Years Ago Today. Ashgate Publishing Limited. Hampshire, UK, 2008. Lewisohn, Mark. The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions: The Official Story of the Abbey Road Years 1962-1970. Harmony Books, a division of Crown Publishers, New York, NY, 1988. Sandford, Christopher. McCartney. Carroll & Graff Publishers, New York, NY, 2006. Sawyers, June Skinner, ed. Read the Beatles: Classic and New Writings on the Beatles, Their Legacy, and Why They Still Matter. Penguin Books, New York, NY, 2006. Simonelli, David. Working Class Heroes: Rock Music and British Society in the 1960s and 1970s. Lexington Books, 2012. Tomson, Elizabeth and David Gutman, ed. The Lennon Companion: Twenty-Five Years of Comment. Sidgwick & Jackson, an imprint of Pan Macmillan Ltd., London, 2002. Wald, Elijah. How the Beatles Destroyed Rock ‘n’ Roll: An Alternate History of American Popular Music. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 2009. In short, Beatlemania was no longer fun for the Fab Four. It inhibited rather than propelled the band's development. "I never felt people came to hear our show," said Ringo in The Beatles Anthology. "I felt they came to see us. Because from the count on the first number the volume of screams would just drown everything out ... The realization was really kicking in that nobody was listening. And that was okay at the beginning, but even worse than that was we were playing so bad. I just felt we're playing really bad. Why I joined the Beatles was because they were the best band in Liverpool. I always wanted to play with good players - that's what it was all about. First and foremost, we were musicians." Paul concurred: "We were getting worse and worse as a band while all those people were screaming. It was lovely that they liked us, but we couldn't hear to play So the only place we could develop was in the studio."

Furthermore, touring was becoming dangerous. Lennon's comments about the Beatles being "more popular than Jesus" prompted massive protests in the American South, as did their performance in Japan's sacred Nippon Budokan Hall, followed by a disastrous tour in the Philipines. Quoting George, also from The Beatles Anthology: "They used us an an excuse to go mad - the world did - and then blamed it on us. And we were just in the middle of it, in a car or a hotel room. We couldn't really do much. We couldn't go out, we couldn't do anything. ... It felt dangerous because everybody was out of hand and out of line - even the cops were out of line. They were all just caught up in the mania. It was like they were in this big movie. We were the ones trapped in the middle of it while everyone else was going mad. We were actually the sanest people in the whole thing." Additionally, the band's recording sophistication developed to the point where tracks like “I'm Only Sleeping” off Revolver were too technically complicated to attempt to reproduce live on stage. The strange sounds used in that song are a guitar solo played backwards. In the studio backwards guitar playing is very easy to do (you simply record your guitar, then play the tape in reverse), but how do you perform a guitar backwards in a live performance? Quite simply, it cannot be done. Lastly, by 1966, all four band members were quite comfortable financially. That lack of monetary need no doubt also contributed to the decision to stop touring. Thus, the combination of (1) touring no longer being enjoyable - and sometimes even dangerous, (2) a deteriorating level of performance quality, (3) an increased level of studio sophistication, and (4) the lack of financial need all greatly contributed to the Beatles decision to stop playing live shows. Following the conclusion of their August 1966 American tour, then, the Beatles retreated to the recording studio to begin the album that would ultimately become Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. CITATIONS Beatles. The Beatles Anthology. DVD. Apple Corps Limited, 2003. Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band has received much acclaim for being the first “concept album”, an album in which a single idea unifies the entire recording (as opposed to most albums, which are simply collections of songs without such an overarching principle). In the case of Sgt. Pepper, that concept was the simulation of a live performance by a fictitious band. But Pepper was not the first concept album.

The definition of exactly what a concept album is remains nebulous, but many at least nascent concept albums predate Sgt. Pepper:

Additionally, the status of Pepper as a concept album never sat well with John Lennon. “It doesn't go anywhere,” he said. “All my contributions to the album have absolutely nothing to do with this idea of Sgt Pepper and his band; but it works, because we said it worked, and that's how the album appeared. But it was not put together as it sounds, except for Sgt Pepper introducing Billy Shears, and the so-called reprise. Every other song could have been on any other album” (Anthology, page 241). However, while there are no macro-scale tonal schemes (which would have to wait until Abbey Road) nor any thematic unity present in every song, the album does roughly follow a narrative of watching a single live production. The tracks help with that flow, with the opening title song followed seamlessly by “With a Little Help From My Friends”; then again at the end of the album, the stampede of animals that closes “Good Morning” leads directly into the reprise of the title track – the guitar lick starting the latter attempting to sound like the chicken cluck ending the former, with the reprise in turn segueing into the epic “A Day in the Life”. So is Pepper a true concept album? Well, yes and no. With strong cases being made both ways, it's one of those times where each listener has to decide for him- or herself exactly what the definition of "concept album" is, and then determine if Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band fits that category. To a certain extent, the question of definition is moot. Shakespeare famously said, "A rose by any other name would smell as sweet", and he's right - what you call something does not fundamentally change what that something is. Like the debate over whether Pluto is or is not a planet, the definition can change the answer, but not the object. Regardless, what Pepper did was bring the idea of a concept album to the attention of the mass media and public – it was (and arguably still is) the most famous example of one. In doing so, Sgt. Pepper legitimized the rock album just as the song “Yesterday” had legitimized the pop song two years earlier - an artistic achievement arguably unequaled before or since. CITATIONS Beatles. The Beatles Anthology. Chronicle Books, San Francisco, CA, 2000. The White Album served as the perfect antithesis to Sgt. Pepper. What, after all, could have been more different from Pepper's collage cover than plain white? And what could have been more different from Pepper's “concept album” layout, in which the entire record can be viewed as a single large-scale product, than a series of rather aimless fragments?

One of the most common sentiments regarding The White Album is that it should have been whittled down to a single album instead of a double album; but that means omitting half of the songs, and which ones go and which ones stay is a point of tremendous contention. In fact, if you want to start a fight among Beatles fans, this might be the surest way to do so. One major reason for the album being a double is that the three songwriting Beatles all wanted their songs to be included - they all felt that their material was worthy of the album. Thus, the album grew because neither John nor Paul nor George wanted any of their songs cut. This insistence, however, was only the tip of the iceberg - the symptoms of a much greater, more fundamental problem: All four Beatles were growing apart, and wanted to spend progressively more time pursuing their own individual projects rather than unified Beatles projects. In fact, when asked when the Beatles broke up, John Lennon indicated The White Album, because, “Every track is an individual track – there isn't any Beatles music on it. … It was John and the band, Paul and the band, George and the band” (Cott, page 88). Here again, what could be further from Sgt. Pepper? CITATIONS Cott, Jonathan, ed. and Christine Doudna, ed. The Ballad of John and Yoko. Rolling Stone Press, Dolphin Books, Double Day & Company, Inc, Garden City, NY, 1982. In the film A Hard Day's Night, at the very beginning, is a scene in which John Lennon, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr are being chased by a mob of screaming girls. Paul McCartney, however, avoided the problem by wearing fake facial hair, thereby disguising his identity and saving himself the trouble of dealing with the hysteria. The tactic was not created for the film - Paul actually used the trick on a regular basis. It had a liberating effect, allowing him to walk around in public without the debilitating insanity of Beatlemania. For those few hours, it was as if he was someone other than Paul McCartney.

Indeed, the disguise worked so well that the bassist wondered if the same stunt could be employed by the whole band. Just as it did with Paul, assuming different identities could free the band to try different things by allowing the group to get outside of themselves. Quoting Paul: "With our alter egos we could do a bit of B. B. King, a bit of Stockhausen, a bit of Albert Ayler, a bit of Ravi Shankar, a bit of Pet Sounds, a bit of the Doors; it didn't matter, there was no pigeon-holing like there had been before" (Miles, page 306). After a crazy year in 1966 - in which they stopped touring due in large part to the delirium of live performances - the band found the notion quite appealing, and decided that for their next album they would not be the Beatles. Citations Miles, Barry. Paul McCartney: Many Years From Now. Henry Holt and Company, New York, NY, 1997. |

Beatles BlogThis blog is a workshop for developing my analyses of The Beatles' music. Categories

All

Archives

May 2019

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed