|

Formal structure of "Strawberry Fields Forever":

Intro (verse) 0:00-0:10 Chorus 0:10-0:34 Verse 1 0:34-0:55 Chorus 0:55-1:21 Verse 2 1:21-1:41 Chorus 1:41-2:04 Verse 3 2:04-2:26 Chorus 2:26-3:00* Coda (ind.) 3:00-4:07* Comments: Given my extensive analyses of this song in previous blog posts, I will refrain from redundancy and comment only on those aspects not previously discussed. The last chorus is extended by repeating the title lyrics two additional times. "Strawberry" is just the second Beatles track so far to use a palindromic formal structure. (The other being [33] "I'll Be Back".) At 67 seconds in duration, "Strawberry Fields" features the longest coda of any Beatles song to date. (The next longest are [13f] "Please Mister Postman" at 49 seconds, and [13c] "Money (That's What I Want)" at 48 seconds.)

0 Comments

As a follow-up to my series of blogs about "Strawberry Fields Forever", here is a PDF document illustrating the development of the song over the course of the six takes Lennon recorded in Spain during 1966.

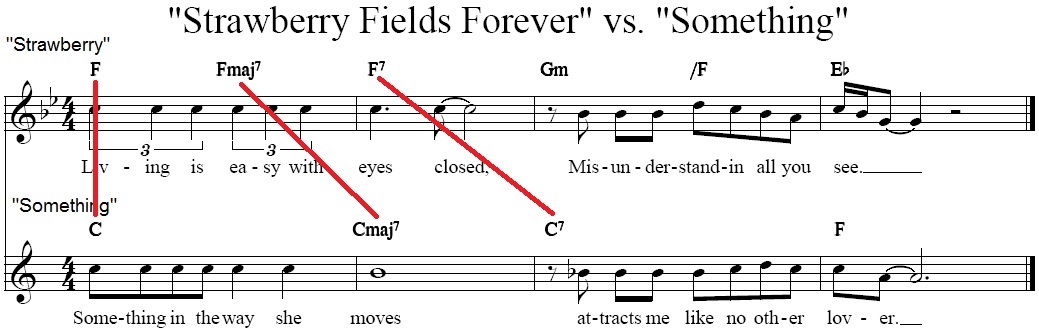

The first three chords of the verses in "Strawberry Fields Forever" and "Something" share a certain degree of similarity. Though in different keys ("Something" is in C Major; "Strawberry" in B-flat major) and using different chords ("Something" uses C; "Strawberry" F) based on different scale degrees ("Something" uses the tonic chord; "Strawberry" the dominant), the qualities of those three chords are the same: major, major 7, 7. Here's a graphic to illustrate the similarity (click to enlarge):

This lecture will be premiered this evening, Wednesday, May 15, 2013, from 6:30-7:30 p.m. at Cora J. Belden Library, 33 Church Street, Rocky Hill, CT. "Strawberry Fields Forever" is quite well-known for its famous splice between Takes 7 and 26 (discussed at length in my 11 April 2013 blog), and the additional chorus that was edited in (as discussed in my 12 May 2013 blog), but there is yet another major edit that survived to the released recording, and it is that third edit that will be discussed in this post. Quoting George Martin: "There is the end section of the orchestrated version of the song, where the rhythm is too loose to use. In spite of all our editing, I just could not get a unified take with complete synchronicity throughout. The obvious answer would have been to fade out the take before the beat goes haywire. But that would have meant discarding one of my favourite bits, which included some great trumpet and guitar playing, as well as the magical random mellotronic note-waterfall John had come up with. It was a section brimming with energy, and I was determined to keep it. We did the only thing possible - we faded the song right out just before the point where the rhythm goes to pieces, so the listener would think it was all over, then gradually faded it back up again, bringing back our glorious finale” (Martin, page 23-24). That is why the final edit of "Strawberry Fields Forever" fades out, then fades back in, before fading out once more. That original recording (with its “too loose to use” rhythm), may be found in this YouTube video at 6:40. And here is the finished product (with the fade out, fade back in, and then fade out again), heard around 3:28. CITATIONS

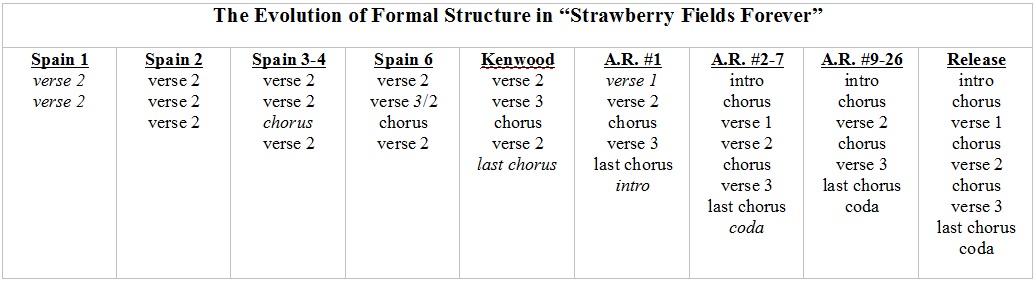

Martin, George with William Pearson. With a Little Help from My Friends: The Making of Sgt. Pepper. Little Brown and Company, Boston, MA, 1994. In previous posts, I have discussed the famous splice exactly 60 seconds in to "Strawberry Fields Forever". But this splice isn't the only major edit in the song. Careful observation shows the addition of an extra chorus in the released version. The first half of the released edit uses the introduction, first chorus, and first verse of Take 7, followed by a second chorus, during which the splice occurs. But Take 7 does not use a chorus immediately following the first verse. The first seven words of either the second or final chorus (they're practically identical so it makes no appreciable difference which of the two - but it is clearly one of the two) are inserted before the splice to Take 26. This notion is much more easily understood visually than aurally, and for that reason I have included a graphic below (click to enlarge). In this graphic, the blue rectangles shows what was used from Take 7, while the red shows what was used from Take 26. But notice that the chorus following verse 1 in the released version does not exist in Take 7 (where instead verse 2 follows verse 1). The blue parentheses, then, illustrate that missing link.

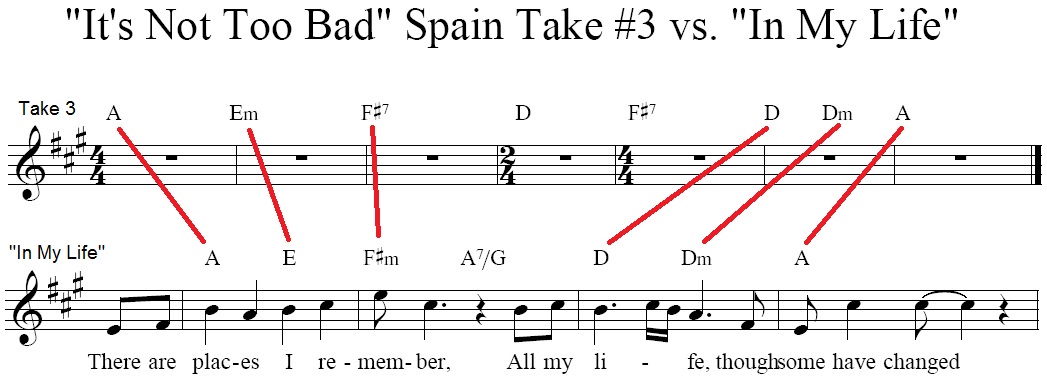

A Comparison of the Chord Progressions of "It's Not Too Bad" Spain Take #3 with "In My Life"4/20/2013 John Lennon's third take of "It's Not Too Bad" (the original title of "Strawberry Fields Forever") is the first instance of what would ultimately evolve into the chorus. But at this early point, it merely consists of a chord progression - no lyrics or melody. That progression features similarities to the chord progression Lennon used a year previously in "In My Life". The graphic below illustrates these similarities. (Click to enlarge.)

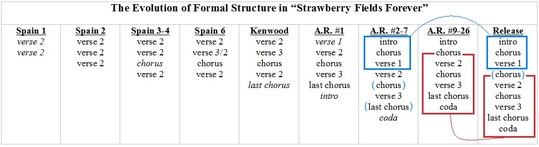

Having recently completed my 13-part blog history of "Strawberry Fields Forever", now it is time to start putting it all together and draw conclusions. To aid in this, I have created a diagram illustrating how the structure of "Strawberry Fields Forever" evolved from Lennon's initial recordings in Spain, through the release. (Click to enlarge.) Sections are indicated by where they appear on the released recording (which is why Abbey Road Take 1 concludes with the introduction). New structural developments are shown in italics

When "Strawberry Fields Forever" was completed in December 1966, it was intended to be released on the band's next album, eventually titled Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. However the band hadn't released any new material since Revolver in August 1966 - a span that would ultimately stretch into 6 months, the longest such drought of the Beatles' entire career. Thus, critics began to postulate that perhaps the Beatles were through, maybe the bubble had finally burst. In an effort to prove them strikingly wrong, the Beatles released the double-A-side single "Strawberry Fields Forever"/"Penny Lane". Despite the name, singles actually feature two songs. This is, of course, because a vinyl pressing has two sides - to release a vinyl single would necessarily mean releasing one of those two sides blank - so it makes sense to include two songs on a single. With those two songs, singles tend to work best when there is a clear hierarchy - where one song is clearly superior to the other - and this notion is easily reinforced by the two sides of the vinyl disc: one side is the "A side", featuring the superior song, while the other is the "B side", featuring a weaker song. But the Beatles instead opted for a single in which the two sides were equal, thus the release of the "double-A-side single". Martin always regretted the decision of a double-A-side single. "It was the biggest mistake of my professional life. ... If I had stopped to think for more than about a second, I would have realized that one great title would fight another; and this is exactly what happened. The reports came in, and they showed that our double-A-side was selling extremely well. There was only one problem. The weekly sales figures showed that two singles, 'Strawberry Fields Forever' and 'Penny Lane', were selling well. They were being counted separately! As far as the charts were concerned, one side was effectively canceling out the success of the other. I firmly believe that if the total sales of those two sides had been added together we would have squashed the opposition flat" (Martin, page 26). Instead, it broke the Beatles' string of 12 consecutive number one hits, beaten out by Englebert Humperdinck's "Release Me". "We had agreed that if a song had been released as a hit single, we should try not to use it as a cynical sales-getter on a subsequent album. To our way of thinking, this was asking people to pay twice for the same material. I know it seems ludicrous these days: now a hit single is frequently used to sell a whole album; but we thought differently then. This was why 'Strawberry Fields Forever' and 'Penny Lane' did not make it on to Sgt. Pepper as originally intended" (Martin, page 26). In America, however, where record companies had no such moral qualms, both tunes surfaced both as a single and on the Magical Mystery Tour album.

CITATIONS Martin, George with William Pearson. With a Little Help from My Friends: The Making of Sgt. Pepper. Little Brown and Company, Boston, MA, 1994. With the completion of take 7 on 29 November 1966, everybody thought "Strawberry Fields Forever" was finished. Everybody except John Lennon. So take 7 was ditched and the Beatles re-recorded the song from scratch. Then, with the completion of take 26 on 21 December 1966, everybody thought "Strawberry Fields Forever" was finished. Everybody except John Lennon. "Ever the idealist, and completely without regard for practical problems, John said to me, 'I like them both. Why don't we join them together? You could start with Take 7 and move to Take [26] halfway through to get the grandstand finish.' 'Brilliant!' I replied. 'There are only two things wrong with that: the takes are in completely different keys, a whole tone apart; and they have wildly different tempos. Other than that, there should be no problem!' John smiled at my sarcasm with the tolerance of a grown-up placating a child. 'Well, George,' he said laconically, 'I'm sure you can fix it, can't you?' whereupon he turned on his heel and walked away" (Martin, page 22). Lennon, notoriously inept and ignorant at technical specifics and intricacies, had no idea what he was actually asking George Martin to do. If he had understood, he might not have made such a request. Nevertheless, it is a testament to George Martin's and Geoff Emerick's technical skill that they found a way to make it work. The problem is that take 7 is in B-flat major at a tempo of 90 beats per minute, while Take 26 is in C major and at a tempo of 108 beats per minute - both higher-pitched and faster. To splice these two takes together as they were (i.e. without altering the original in any way) would have sound like this:

The whole point of editing, of course, is to hide the edit - a good edit is one that doesn't sound edited. If a listener can tell that a recording has been edited, then it is not a very good one, and the file above is an extreme example. So how to make these two disparate takes fit together to the point of not sounding edited? Using tape methods of recording, pitch and tempo are inextricably intertwined - if you change one, in doing so you necessarily also change the other. (In the digital age, of course, computers can alter pitch and/or tempo independently of each other, but in the 1960's that was not the case.) In what is probably the greatest coincidence in the entire Beatles saga, the two takes were proportionately equivalent - meaning that if take 7 were sped up, and take 26 slowed down, they could match both in tempo and tonality. But this, too, presented problems: "George and I decided to allow the second half to play all the way through at the slower speed; doing so gave John's voice a smokey, think quality that seemed to complement the psychedelic lyric and swirling instrumentation. Things were a bit trickier with the beginning section; it started out at such a perfect, laconic tempo that we didn't want to speed it up all the way through. Luckily, the EMI tape machines were fitted with very fine varispeed controls. With a bit of practice, I was able to gradually increase the speed of the first take and get it to a certain precise point, right up to the moment where we knew we were going to do the edit. The change is so subtle as to be virtually unnoticeable" (Emerick, page 140). (Parenthetically, I can hear the tempo difference, but what remains a mystery to me is why there is not a corresponding difference in pitch. The whole point of this "splice story" is predicated on the fact that if you change one, you necessarily also alter the other - and yet here it appears that somehow the tempo was changed while the pitch was not. I have absolutely no idea how...) After many hours of work, George and Geoff had a finished product. Though expertly masked, the splice can still be heard at precisely 1:00. (It is easiest to hear the edit if you listen to the drums.) Don't be embarrassed if you cannot hear it - neither could John Lennon. "As we played the results of our labours to John for the first time, he listened carefully, head down, deep in concentration. I made a point of standing in front of the tape machine so that he couldn't see the splice go by. A few seconds after the edit flew past, Lennon listed his head up and a grin spread across his face. 'Has it passed yet?' he asked. 'Sure has,' I replied proudly. 'Well, good on yer, Geoffrey!' he said. He absolutely loved what we had done. We played 'strawberry Fields Forever' over and over again that night for John, and at the conclusion each time, he'd turn to use and repeat the same three words, eyes wide with excitement: 'Brilliant. Just brilliant.'" (Emerick, page 140).

There is another major edit at the end of the song that also survived to the released recording. "There is the end section of the orchestrated version of the song, where the rhythm is too loose to use. In spite of all our editing, I just could not get a unified take with complete synchronicity throughout. The obvious answer would have been to fade out the take before the beat goes haywire. But that would have meant discarding one of my favourite bits, which included some great trumpet and guitar playing, as well as the magical random mellotronic note-waterfall John had come up with. It was a section brimming with energy, and I was determined to keep it. We did the only thing possible - we faded the song right out just before the point where the rhythm goes to pieces, so the listener would think it was all over, then gradually faded it back up again, bringing back our glorious finale" (Martin, page 22-23). With Lennon (finally) satisfied, "Strawberry Fields Forever" was (and remained) complete. It was now ready for release. CITATIONS Emerick, Geoff with Howard Massey. Here, There and Everywhere: My Life Recording the Music of The Beatles. Gotham Books, New York, NY, 2006. Martin, George with William Pearson. With a Little Help from My Friends: The Making of Sgt. Pepper. Little Brown and Company, Boston, MA, 1994. |

Beatles BlogThis blog is a workshop for developing my analyses of The Beatles' music. Categories

All

Archives

May 2019

|

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed