|

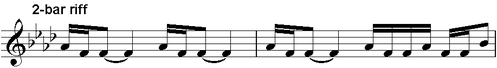

Another example of rhythmic displacement can be found in “When the Levee Breaks”, the concluding track of Led Zeppelin IV (1971). Jimmy Page's guitar and John Paul Jones' bass play in unison throughout the verses. Their basic riff is a single-measure blues pattern: But often they extended it by twice repeating the first half of the 1-bar riff, yielding a 2-bar riff: Following the initial two measures of solo drums, the introduction continuously juxtaposes these two riffs.

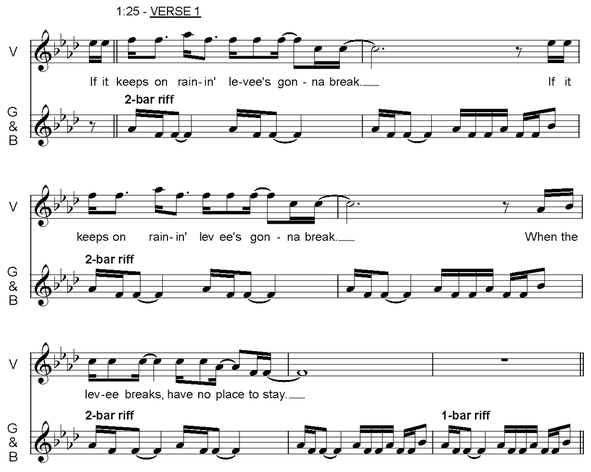

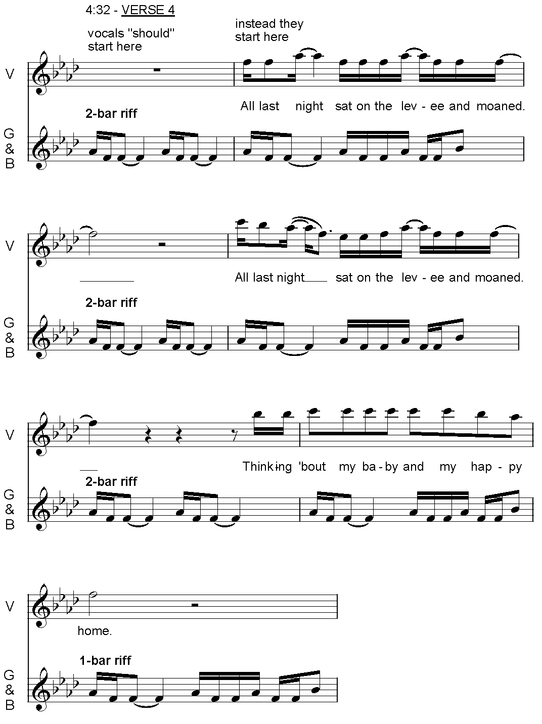

This constant varying of riff durations wards off any threat of monotony and foreshadows the riff patterns used in the verses. Notice how from 0:21-0:44 and from 0:44-1:08 the 2-bar riff is played three times followed by the 1-bar riff once. This seven-measure pattern will be heard in all four verses, where Robert Plant's vocals are added to Page's and Jones' riffs. Since Plant's verse vocals feature three phrases, each two measures long, they coordinate nicely with the 2-bar riffs. The single 1-bar riff at the end of the verse, then, functions as a turnaround, propelling the song to its subsequent section. 1:25-1:49 = Verse 1 (7 measures) 1:25 = 2-bar riff (“If it keeps on raining...”) 1:32 = 2-bar riff (“If it keeps on raining...”) 1:38 = 2-bar riff (“When the levee breaks...”) 1:45 = 1-bar riff (instrumental) That same coordinated pattern is also found in the second and third verses... 1:49-2:13 = Verse 2 1:49 = 2-bar riff (“Mean old levee...”) 1:55 = 2-bar riff (“Mean old levee...”) 2:02 = 2-bar riff (“It's got what it takes...”) 2:09 = 1-bar riff (instrumental) 4:09-4:32 = Verse 3 4:09 = 2-bar riff (“Cryin' won't help...”) 4:15 = 2-bar riff (“Cryin' won't help...”) 4:22 = 2-bar riff (“When the levee breaks...”) 4:29 = 1-bar riff (instrumental) … but not in the fourth verse. In this final iteration, Page and Jones continue as usual while Plant displaces his vocals not by one beat, as we saw in "Dazed and Confused", but by one measure. He "should" start singing at 4:32, but instead enters at 4:36, midway through the 2-bar riff, offsetting the coordinated pattern heard in the three previous verses.

Since the underlying harmony throughout the verses is static, this rhythmic displacement does not cause any harmonic problems the way such a displacement would in, say, "Babe I'm Gonna Leave You" or “Stairway to Heaven” where the harmonies are more fluid.

1 Comment

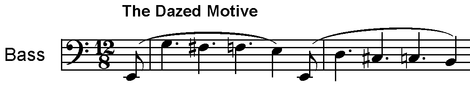

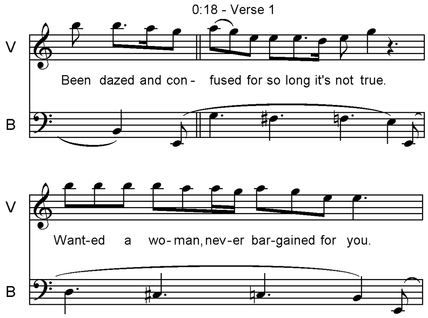

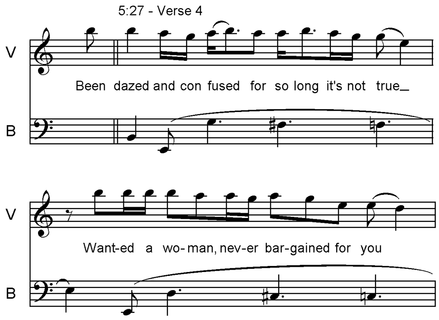

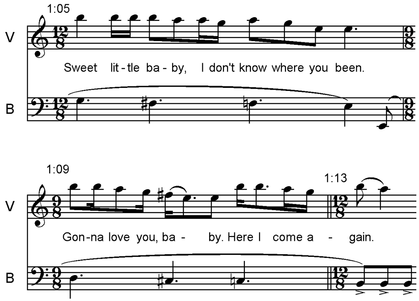

It's no secret that Led Zeppelin loves playing with rhythm. And one of their favorite stunts is establishing a rhythmic expectation early in a song, then thwarting that expectation later through a compositional technique known as rhythmic displacement. I have several examples in mind, and I'll dedicate one blog for each. To start, let's look at “Dazed and Confused”, the fourth track of Zeppelin's self-titled debut album from 1968. The first thing heard on the track is John Paul Jones' bass playing two measures, each consisting of four chromatically descending tones, and each with an anacrusis - what I'll call “The Dazed Motive” due to its rather wobbly feel. That Dazed motive is heard a total of 16 times. The first eight instances (heard consecutively from 0:00-1:13) all start on beat one, as illustrated above. But the last eight instances (heard four times from 1:21-1:57, and another four times from 5:11-5:45) all displace the motive one full beat – they all start on beat two, as illustrated below. But it's not just Jones' bass that is displaced – it's Robert Plant's vocals, as well. At first, Plant places the syllable “fused” from “confused” on the downbeat (0:18), delineating the official start of the first verse. And he does the same phrasing (but with different lyrics) with the second verse (0:55). But with verses three and four, his entry is delayed one beat. Since verse 4 begins with the same lyrics as verse 1, it makes for an ideal apples-to-apples comparison. Additionally, Jimmy Page's guitar is also displaced one beat. I won't provide examples for that, however, since it's identical to Jones' bass. In fact, the only instrument not displaced is John Bonham's drums. And it's the percussion that confirms that a displacement has indeed happened. Because obviously if the drums were displaced one beat, just like every other instrument, then this would be a case of changing meters – not displacement. Since changing meters is another favorite rhythmic technique of Zeppelin, it's slightly surprising that we don't find more meter changes in “Dazed and Confused”. Their rhythmic instability could be put to good use in a song with this title. And yet, there are just two instances of measure(s) in a meter other than 12/8. The more obvious instance comes during the up-tempo middle section, from 3:30-5:02, where a metric modulation of eighth=quarter yields a fast 4/4 meter. The less obvious but more significant instances comes at the end of the second verse (1:09), which is abbreviated by one beat from a 12/8 bar (as it was in verse 1) to a 9/8. After this single measure of 9/8, the pitched instruments are consistently displaced while the drums are not. So this 9/8 measure might be thought of as the catalyst for the subsequent rhythmic displacement. And it's for that reason that this 9/8 measure is my personal favorite measure in the entire song :-)

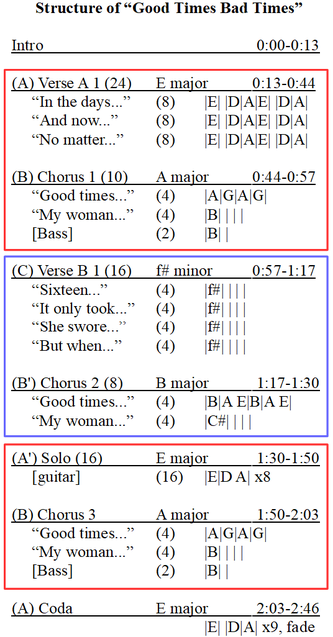

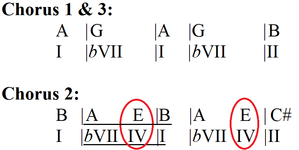

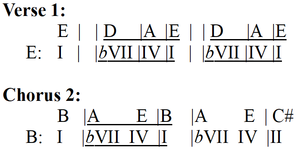

I started the analytical (as opposed to the introductory) part of the blog yesterday with a structural analysis of “Whole Lotta Love”. In it, I implied that early Zeppelin songs illustrate how they grew out of their predecessors like The Beatles. That is true to a certain extent, but that's not entirely true. I oversimplified a bit. Of course there are exceptions. And as evidence to the contrary, I present a structural analysis of “Good Times Bad Times”, the opening number of Zeppelin's 1968 self-titled debut album, which has a unique (to my knowledge, anyway) formal design. Get a load of this oddity!: Okay, so, the first thing to notice is that there are two distinct verses, here labeled Verse A and Verse B. While The Beatles occasionally employed multiple different verses within the same song (check out “Glass Onion” or “Lovely Rita”), it's rare. I don't know other bands' oeuvres well enough to cite a non-Beatles example off the top of my head, but I'm sure there are examples to be found. Some scholars have debated with me over the justification for using multiple verses instead of other labels. “Rita”, for example, is often analyzed as using verses and bridges instead of multiple verses. I certainly see the point, but I maintain these are all verses for reason I won't get into here. In any case, “Good Times” definitely uses multiple verses because each section in question is paired with a chorus – exactly what would be expected of verses. The second thing that stands out is that the chorus also has two different iterations. The distinction here is harmonic: The first and third choruses are in A major, while the second is in B major. This middle chorus grows organically out of what was heard in the first chorus as it adds an E chord (IV) on the third beats of the second and fourth measures, circled red in the example below. This addition results in a double plagal cadence (A-E-B, bVII-IV-I, underlined below) from the second to third measures. This ties in to the harmony of the initial verse (shown in the example below), which also employs double plagals but in E major (D-A-E) and twice as long (four measures where the same pattern in the chorus lasts only two). Also, the middle chorus elucidates the tonality of the outer choruses. The first and third choruses are harmonically ambiguous on their own – are they really in A major? We don't necessarily have enough information to make that claim - there are no cadences to confirm such a conclusion. But the addition of those double plagals in the middle chorus implies that the harmony of the first and third can be interpreted as “incomplete double plagal cadences” which are missing the IV chord. With that in mind, we can indeed infer that the outer choruses are in A major.

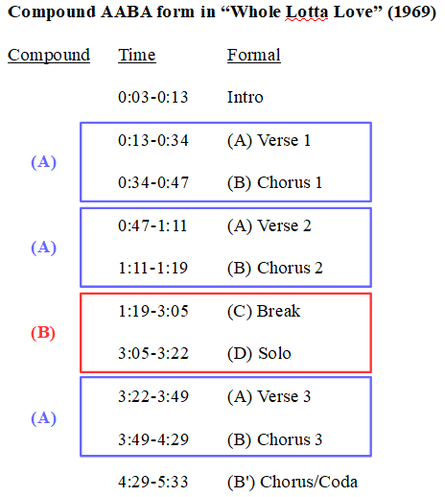

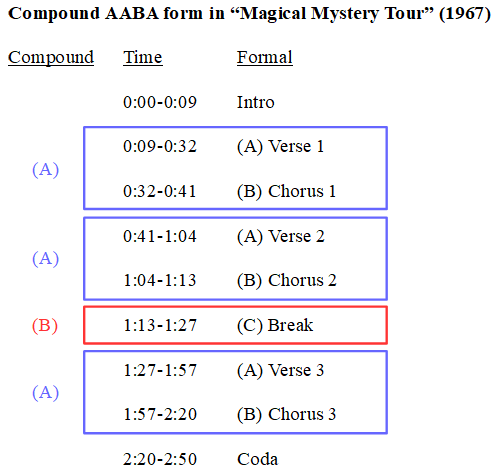

One last thing about the choruses: The middle iteration is abbreviated. While the first and third choruses both feature a two-bar bass transition, the second chorus omits it. This further differentiates the choruses, which strengthens the eventual conclusion (see below) that "Good Times" is a compound ternary structure. Finally, the solo replaces a verse. It employs identical harmonies, but rhythmically halved. This, too, grows organically out of what preceded it. The solo also uses double plagal cadences, just like the first verse and second chorus. It uses the tonality of the verse's double plagals (D-A-E) but with the chorus's rhythms (two measures instead of four). So the solo is related to both the first verse (through tonality) and to the second chorus (through rhythm). The overall structure of “Good Times Bad Times”, then, is a hybrid AB|CB'|A'B – it's part compound simple (an AB x3 in which the middle AB is actually a CB') and part compound ternary (ABA'). If I had to pick one of those designations, I think the latter more accurately and precisely articulates the form. Even though this song is from Zep's first album, it shows a spectacularly advanced hybrid formal structure and organic development that breaks with their predecessors' work (to the extent of my knowledge). It certainly would not be the last time they would use such a sophisticated musical design. “Whole Lotta Love”, the opening track from Led Zeppelin II, employs a rather conventional compound AABA structure. The verses and choruses combine to constitute the compound A sections, while the break and solo combine to create the compound B section. While The Beatles employed AABA structures frequently (121 of their 211 songs use some type of AABA design), they used relatively few compound AABA structures. The most famous of that handful is “Magical Mystery Tour”, which, though not identical to “Whole Lotta Love”, is strikingly similar in form. So what does this mean? It's an example of how Led Zeppelin grew out of what came before them. Of course this doesn't necessarily mean that Jimmy Page and Robert Plant were deliberately mimicking John Lennon and Paul McCartney – I highly doubt they were – but here we have an early Zeppelin recording that employs a similar structure to a late Beatles track. Just a few years later, Zeppelin would record “Black Dog” and “Stairway To Heaven” and “Kashmir”, all of which use much more experimental and innovative formal designs which depart from and build off of structures employed by The Beatles. And I'll look in detail at those songs soon.

On the first day of May last year, just over one hour after submitting the final drafts of both volumes of BEATLESTUDY, I boarded a plane at the Indianapolis airport with the destination of Denver, Colorado. That flight marked the start of a lecture tour from Colorado through Kansas and Missouri. Reprising the notion from Days in the Life, it was another trip with my Dad, who picked me up at the Denver airport.

On our long drive east, we of course listened to many hours of music. We carefully compared the mono vs. stereo versions of The Beatles' Rubber Soul and Sgt. Pepper. We listened to the audio book Fire and Rain by David Browne. And at one point, Dad put in The Best of Led Zeppelin. I knew of Zeppelin, of course, but I didn't know much about them. I could hum a bit of “Stairway to Heaven”, but not much more. I realized pretty quickly, however, that I knew a lot more Zeppelin than I thought I did. I'd heard “Immigrant Song” in the film Shrek, but I didn't realize at the time that it was Zeppelin. And I'd heard “Rock and Roll” frequently, but never realized that was Zeppelin, either. Same could be said about “Kashmir”. The more we listened, the more I recognized. And with BEATLESTUDY finally complete (after five years of work), I had my antennae out for something new. Might Zeppelin be next? A month later, I drove north from Indiana into Michigan for a conference at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor. The four-hour drive was long enough to listen to their first five albums. Houses of the Holy was still in the CD player when I gave my good friend, fellow conference speaker, and editor of BEATLESTUDY, voulme 1 David Thurmaier a lift back to his hotel one night. Dave was air-drumming along in the passenger seat as soon as the music kicked in. He was obviously much more knowledgeable about this band than I was. I'd be lying if I said I wasn't a tiny bit embarrassed that he knew these songs so well while I didn't know them at all. “You're gonna have to read up on Zeppelin and listen to their albums some more,” I tactitly told myself. Fast forward to 29 October 2017. I'm eating dinner at Riverside Pub & Grille in Bel Air, MD with librarians Betsy Bensen and Joyce Wemer following my presentation The Beatles' Alter Ego, Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band at the Bel Air library. In addition to discussing The Beatles, we also debate the musical merits of other rock bands. I put forth a nascent idea for a program titled Stairway to Zeppelin, in which I'd look at how 1960s bands like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones paved the way for Led Zeppelin in the 1970s. Though not big Zeppelin fans, Betsy and Joyce both expressed interest. I decided to add it to my repertoire document and shop it around to other libraries for future lecture tours. Indeed, I got a bite from the Richards Memorial Library in North Attleboro, MA, and so Stairway to Zeppelin is scheduled to debut on 12 July 2018. So now I have to get to work! My composition teacher at Butler University, Dr. Michael Schelle, once told me, “A deadline is the second strongest motivator behind a paycheck.” And now I have both compelling me to study Led Zeppelin. Much like The Beatles literature, the problem with the extant Zeppelin literature is that so little of it focuses on the music. Many books seem more concerned about lurid descriptions of orgies, or Jimmy Page's obsession with the occult and Aleister Crowley, or “hidden meanings” in their lyrics and album artwork than they are about the actual music. Again like The Beatles, it astounds me that so much can be written about musicians while so little is written about the work. It is, after all, the music – not their salacious love lives or hotel-trashing – that makes Led Zeppelin compelling and worthy of study and criticism a half century later. Indeed, I've been painstakingly transcribing Zep songs for the last week or so, and the more I study the more I respect their musical artistry. Yet again like The Beatles, the compositional sophistication balanced with accessibility never ceases to amaze me. And so today I launch a new blog dedicated to Led Zeppelin. Just like my Beatles blog, it'll be a workshop for me to develop my ideas as I digest their catalog. Happy listening! |

Aaron Krerowicz, pop music scholarAn informal but highly analytic study of popular music. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed