|

We've already seen how 'Dazed and Confused' and 'Houses of the Holy' displace one beat (though in opposite directions), how 'When the Levee Breaks' displaces one measure, and how 'Stairway to Heaven' displaces by two beats and by an entire phrase. Next and last in this series is a song that displaces half a beat: 'Black Dog', the initial track of Led Zeppelin IV (1971). In this case, a seven-note pattern lasting nine eighth notes... ...is repeated over common time measures, yielding rhythmic displacement of a single eighth note (half a beat) per iteration. Lesser musicians might have repeated these musical ideas more or less the same each time. But Zeppelin, ever attentive to detail, found ways to subtly alter their music in a way simultaneously familiar yet different through rhythmic displacement. And that, I suspect, is one trait (of many) that separates the good bands from the great bands.

0 Comments

Last Sunday, I blogged about the rhythmic displacement of Robert Plant's 'When the Levee Breaks' vocals through Plant starting the fourth verse at the "wrong" time (a measure late, in that case). I concluded that blog by writing, "Since the underlying harmony throughout the verses is static, this rhythmic displacement does not cause any harmonic problems the way such a displacement would in, say, 'Babe I'm Gonna Leave You' or 'Stairway to Heaven' where the harmonies are more fluid." And yet I just discovered the other day that Plant does use that same "start at the wrong time" displacement technique in 'Stairway to Heaven' - not one measure late, like 'Levee', which certainly would cause clashes with the underlying harmony, but rather an entire phrase early (in this case, four measures).

The instrumental introduction establishes a four-square phrase pattern (four phrases, each four measures long). The first and second phrases are identical, so they're both labeled (a). And the third and fourth phrases are nearly identical, so they're labeled (b) and (b'). 0:00-0:54 Instrumental Introduction (16 measures) 0:00 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | 0:14 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | 0:27 (b) |C D |FM7 a |C G |D | 0:40 (b') |C D |FM7 a |C D |FM7 | Plant's entry marks the start of the first verse at 0:54. That verse employs identical four-square harmony as the introduction. The first phrase (0:54) corresponds to the lyrics "There's a lady...", the second phrase (1:07) to "When she gets..." Though the lyrics are different, the pitches and chords to which those lyrics are sung are essentially identical - the same melody and harmony are repeated, just with different words. That should come as no surprise as it is EXTREMELY common in all genres of pop music The third phrase (1:21), being harmonically different from the first two, has a correspondingly different sung melody (though the ending is quite similar). The fourth phrase (1:34) is where things get really interesting. As was the case in the intro, the harmonies of the fourth phrase are comparable to the third phrase. Yet Plant's singing is comparable to the first and second phrases. This means that melodically the fourth phrase should be labeled (a), but harmonically it should be labeled (b'). In other words, there's a certain "divorce" between the melody and harmony. (And yes, I completely understand the connotations of that term in the context of popular music scholarship, and how I'm using it differently than other scholars.) 0:54-1:48 Verse 1 (16 measures) 0:54 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | “There's a lady...” 1:07 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | “When she gets...” 1:21 (b) |C D |FM7 a |C G |D | “Ooo...” 1:34 (a & b') |C D |FM7 a |C D |FM7 | “There's a sign...” Plant "should" have repeated the tune of phrase three ("Ooo...") to match the harmony, saving "There's a sign..." for the start of the second verse (at 1:48). Instead, he displaces that entry by starting verse 2 a full phrase (four measures) early, overlapping with the concluding phrase of the first verse. Another simple example of rhythmic displacement can be heard in “Houses of the Holy”, the fourth track of Physical Graffiti (1975). In this case, rhythmic displacement is built in to the main riff and so repeated frequently throughout the song. A three-beat pattern is first played on beat one, then immediately following on beat four. This syncopated phrasing helps give the track its funky character.

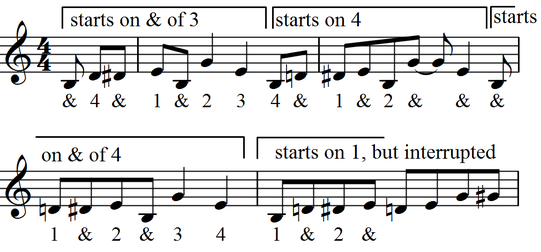

After two rather substantial examples of rhythmic displacement in “Dazed and Confused” and “When the Levee Breaks”, the next two examples will be comparatively lite. In “Stairway to Heaven”, the fourth track of Led Zeppelin IV (1971), Robert Plant sometimes displaces his vocals by two beats during the lyrics “it makes me wonder”. That phrase is heard a total of five times. Since Plant takes some rhythmic liberties between iterations, we'll look at the placement of the word “make” to ensure a fair comparison. In the first and fifth times (at 2:15 and 4:46), “make” falls on beat 4 (highlighted in red in the examples above). But in the second, third, and fourth times (2:27, 3:07, and 3:19), “make” falls on beat 2, (highlighted in blue).

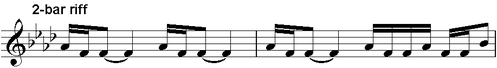

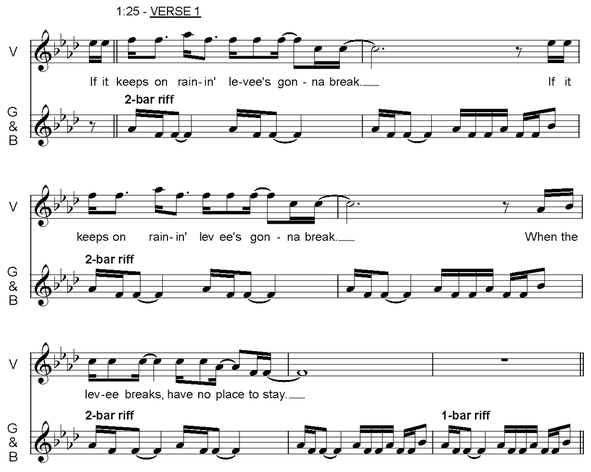

Another example of rhythmic displacement can be found in “When the Levee Breaks”, the concluding track of Led Zeppelin IV (1971). Jimmy Page's guitar and John Paul Jones' bass play in unison throughout the verses. Their basic riff is a single-measure blues pattern: But often they extended it by twice repeating the first half of the 1-bar riff, yielding a 2-bar riff: Following the initial two measures of solo drums, the introduction continuously juxtaposes these two riffs.

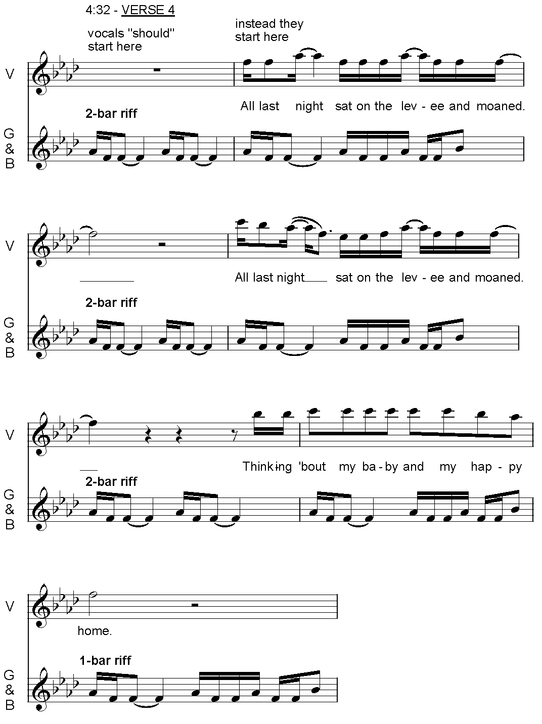

This constant varying of riff durations wards off any threat of monotony and foreshadows the riff patterns used in the verses. Notice how from 0:21-0:44 and from 0:44-1:08 the 2-bar riff is played three times followed by the 1-bar riff once. This seven-measure pattern will be heard in all four verses, where Robert Plant's vocals are added to Page's and Jones' riffs. Since Plant's verse vocals feature three phrases, each two measures long, they coordinate nicely with the 2-bar riffs. The single 1-bar riff at the end of the verse, then, functions as a turnaround, propelling the song to its subsequent section. 1:25-1:49 = Verse 1 (7 measures) 1:25 = 2-bar riff (“If it keeps on raining...”) 1:32 = 2-bar riff (“If it keeps on raining...”) 1:38 = 2-bar riff (“When the levee breaks...”) 1:45 = 1-bar riff (instrumental) That same coordinated pattern is also found in the second and third verses... 1:49-2:13 = Verse 2 1:49 = 2-bar riff (“Mean old levee...”) 1:55 = 2-bar riff (“Mean old levee...”) 2:02 = 2-bar riff (“It's got what it takes...”) 2:09 = 1-bar riff (instrumental) 4:09-4:32 = Verse 3 4:09 = 2-bar riff (“Cryin' won't help...”) 4:15 = 2-bar riff (“Cryin' won't help...”) 4:22 = 2-bar riff (“When the levee breaks...”) 4:29 = 1-bar riff (instrumental) … but not in the fourth verse. In this final iteration, Page and Jones continue as usual while Plant displaces his vocals not by one beat, as we saw in "Dazed and Confused", but by one measure. He "should" start singing at 4:32, but instead enters at 4:36, midway through the 2-bar riff, offsetting the coordinated pattern heard in the three previous verses.

Since the underlying harmony throughout the verses is static, this rhythmic displacement does not cause any harmonic problems the way such a displacement would in, say, "Babe I'm Gonna Leave You" or “Stairway to Heaven” where the harmonies are more fluid.

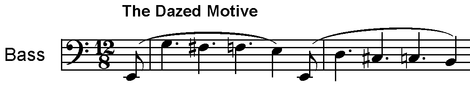

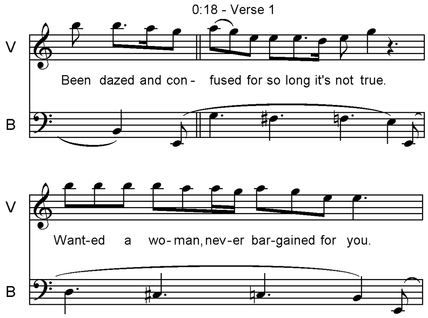

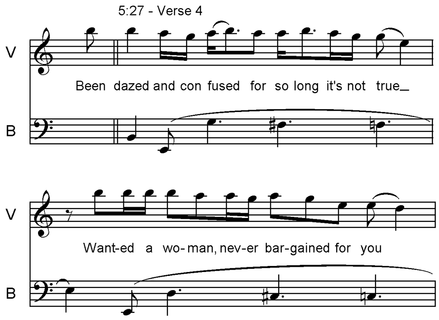

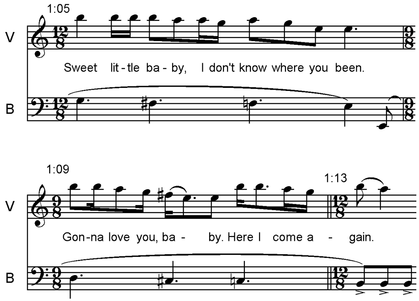

It's no secret that Led Zeppelin loves playing with rhythm. And one of their favorite stunts is establishing a rhythmic expectation early in a song, then thwarting that expectation later through a compositional technique known as rhythmic displacement. I have several examples in mind, and I'll dedicate one blog for each. To start, let's look at “Dazed and Confused”, the fourth track of Zeppelin's self-titled debut album from 1968. The first thing heard on the track is John Paul Jones' bass playing two measures, each consisting of four chromatically descending tones, and each with an anacrusis - what I'll call “The Dazed Motive” due to its rather wobbly feel. That Dazed motive is heard a total of 16 times. The first eight instances (heard consecutively from 0:00-1:13) all start on beat one, as illustrated above. But the last eight instances (heard four times from 1:21-1:57, and another four times from 5:11-5:45) all displace the motive one full beat – they all start on beat two, as illustrated below. But it's not just Jones' bass that is displaced – it's Robert Plant's vocals, as well. At first, Plant places the syllable “fused” from “confused” on the downbeat (0:18), delineating the official start of the first verse. And he does the same phrasing (but with different lyrics) with the second verse (0:55). But with verses three and four, his entry is delayed one beat. Since verse 4 begins with the same lyrics as verse 1, it makes for an ideal apples-to-apples comparison. Additionally, Jimmy Page's guitar is also displaced one beat. I won't provide examples for that, however, since it's identical to Jones' bass. In fact, the only instrument not displaced is John Bonham's drums. And it's the percussion that confirms that a displacement has indeed happened. Because obviously if the drums were displaced one beat, just like every other instrument, then this would be a case of changing meters – not displacement. Since changing meters is another favorite rhythmic technique of Zeppelin, it's slightly surprising that we don't find more meter changes in “Dazed and Confused”. Their rhythmic instability could be put to good use in a song with this title. And yet, there are just two instances of measure(s) in a meter other than 12/8. The more obvious instance comes during the up-tempo middle section, from 3:30-5:02, where a metric modulation of eighth=quarter yields a fast 4/4 meter. The less obvious but more significant instances comes at the end of the second verse (1:09), which is abbreviated by one beat from a 12/8 bar (as it was in verse 1) to a 9/8. After this single measure of 9/8, the pitched instruments are consistently displaced while the drums are not. So this 9/8 measure might be thought of as the catalyst for the subsequent rhythmic displacement. And it's for that reason that this 9/8 measure is my personal favorite measure in the entire song :-)

|

Aaron Krerowicz, pop music scholarAn informal but highly analytic study of popular music. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed