|

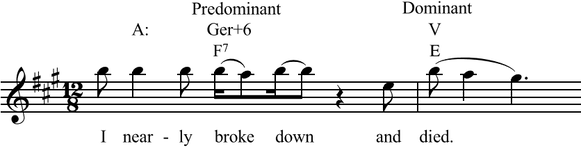

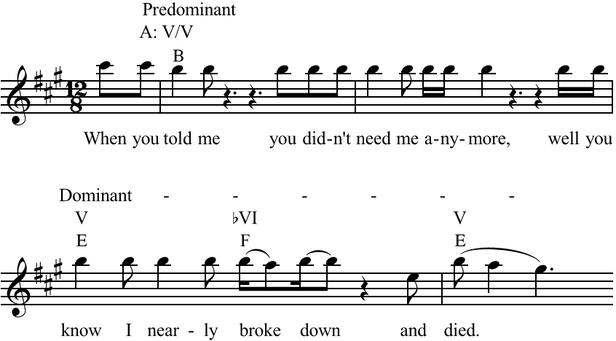

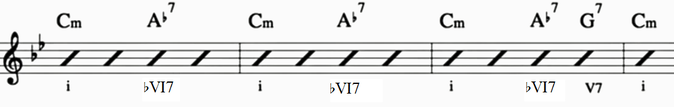

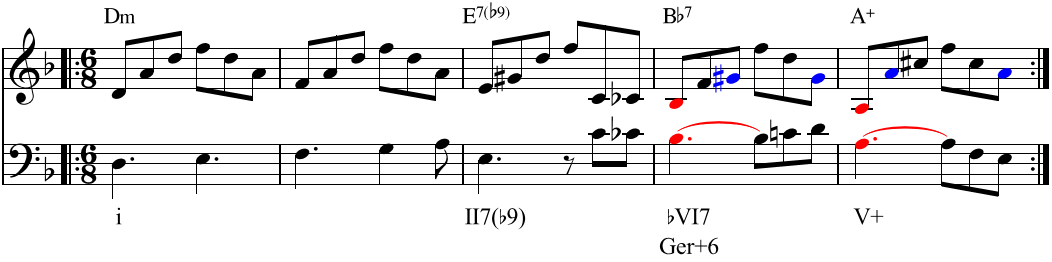

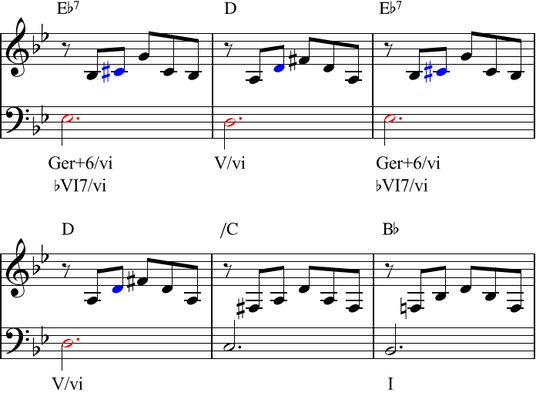

I'll be teaching Theory 3 this fall. In preparation, I've been reviewing the concepts we'll cover, and finding as many pop examples as I can to supplement the textbook's classical examples - including mode mixture, the Neapolitan chord, modulations to distantly-related keys. The next chapter is on augmented sixth chords. Though quite prevalent in the classical repertoire, there seems to be much debate over whether or not augmented sixths are used in popular music. This enthusiastic blogger insists there's one in The Beatles' 'Oh! Darling', arguing that the F7 (bVI in A major) at the end of the bridge functions as an enharmonic German augmented sixth, resolving as any good predominant should to V (in this case E). But there are two glaring problems with his interpretation. First, it's an F chord - not an F7 - which means it cannot be an augmented sixth, even accounting for enharmonics. Second, that F chord is not a predominant. Yes, it progresses to V, but it also progresses from V. So a more careful consideration of the context shows it to be a chromatic upper neighbor, and thus its function is that of a dominant prolongation instead of a predominant. (The predominant is the V/V, B major, heard in the two bars immediately preceding.) So 'Oh! Darling' clearly does not employ an augmented sixth - for multiple reasons. But what about songs where the bVI does have a seventh, and where it truly is a predominant? The following YouTube video gives four such examples. In the first example, Tom Waits' 'Dead and Lovely', he analyzes Ab7 as a Ger+6 in C minor. This is a much better example than 'Oh! Darling', but I maintain that it is not an augmented sixth. The defining characteristic of +6 chords is the voice leading of the augmented sixth resolving outwards to an octave. In this case, however, the seventh of that Ab7 (the note Gb or F#) does not resolve up to G, but rather it planes down to F (the seventh of the G7). Without the proper voice leading, I cannot justify calling the chord an augmented sixth. To do so is to over-complicate an otherwise standard progression. Here's how I would analyze the same passage, without the augmented sixth: I have the same problem (the voice leading discourages an interpretation with an augmented sixth) with the second example, 'Love in My Veins' by Los Lonely Boys. The third and fourth examples, however, do feature proper augmented sixth voice leading, and so in these two instances the +6 is (more) justified. In my transcription of The Beatles' 'I Want You (She's So Heavy)' below, the G#s resolve up to A (shown in blue), while the Bbs resolve down to A (shown in red). This is exactly how augmented sixths should resolve, thus the Ger+6 label is appropriate. The same voice leading (and color coding) is found in 'Blackout' by Muse. So in 'I Want You (She's So Heavy)' and 'Blackout', the Ger+6 interpretation is acceptable, but what advantage is there over simply calling them bVI7? In classical harmony, the augmented sixth chords (especially the Italian and French +6s) cannot be explained any other way - indeed, that's why +6s were invented: to help make sense of something that could not make sense otherwise. But in pop harmony, even the most convincing +6 chords could easily be simplified to bVI7. With nothing to gain through employing +6s in pop harmony analysis, I see no reason to use them.

4 Comments

|

Aaron Krerowicz, pop music scholarAn informal but highly analytic study of popular music. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed