|

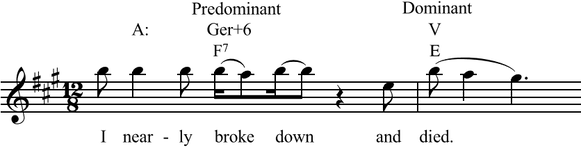

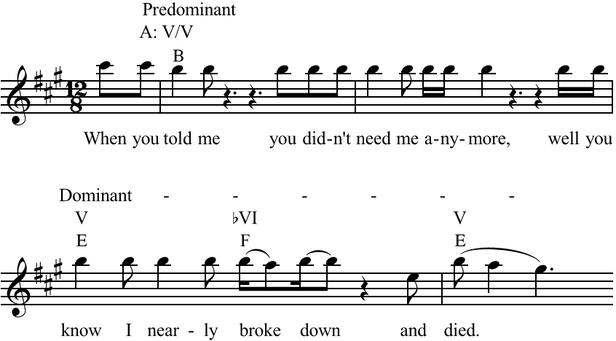

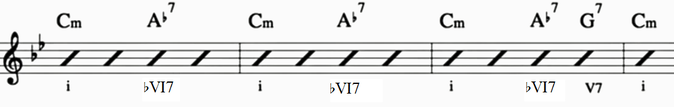

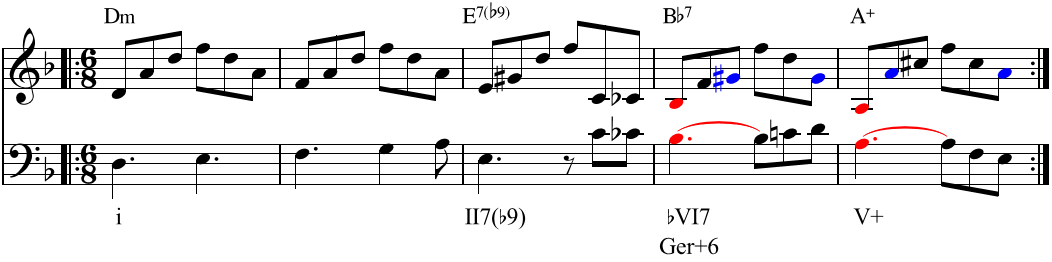

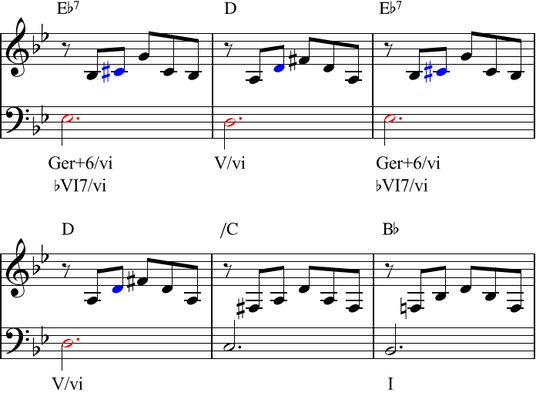

I'll be teaching Theory 3 this fall. In preparation, I've been reviewing the concepts we'll cover, and finding as many pop examples as I can to supplement the textbook's classical examples - including mode mixture, the Neapolitan chord, modulations to distantly-related keys. The next chapter is on augmented sixth chords. Though quite prevalent in the classical repertoire, there seems to be much debate over whether or not augmented sixths are used in popular music. This enthusiastic blogger insists there's one in The Beatles' 'Oh! Darling', arguing that the F7 (bVI in A major) at the end of the bridge functions as an enharmonic German augmented sixth, resolving as any good predominant should to V (in this case E). But there are two glaring problems with his interpretation. First, it's an F chord - not an F7 - which means it cannot be an augmented sixth, even accounting for enharmonics. Second, that F chord is not a predominant. Yes, it progresses to V, but it also progresses from V. So a more careful consideration of the context shows it to be a chromatic upper neighbor, and thus its function is that of a dominant prolongation instead of a predominant. (The predominant is the V/V, B major, heard in the two bars immediately preceding.) So 'Oh! Darling' clearly does not employ an augmented sixth - for multiple reasons. But what about songs where the bVI does have a seventh, and where it truly is a predominant? The following YouTube video gives four such examples. In the first example, Tom Waits' 'Dead and Lovely', he analyzes Ab7 as a Ger+6 in C minor. This is a much better example than 'Oh! Darling', but I maintain that it is not an augmented sixth. The defining characteristic of +6 chords is the voice leading of the augmented sixth resolving outwards to an octave. In this case, however, the seventh of that Ab7 (the note Gb or F#) does not resolve up to G, but rather it planes down to F (the seventh of the G7). Without the proper voice leading, I cannot justify calling the chord an augmented sixth. To do so is to over-complicate an otherwise standard progression. Here's how I would analyze the same passage, without the augmented sixth: I have the same problem (the voice leading discourages an interpretation with an augmented sixth) with the second example, 'Love in My Veins' by Los Lonely Boys. The third and fourth examples, however, do feature proper augmented sixth voice leading, and so in these two instances the +6 is (more) justified. In my transcription of The Beatles' 'I Want You (She's So Heavy)' below, the G#s resolve up to A (shown in blue), while the Bbs resolve down to A (shown in red). This is exactly how augmented sixths should resolve, thus the Ger+6 label is appropriate. The same voice leading (and color coding) is found in 'Blackout' by Muse. So in 'I Want You (She's So Heavy)' and 'Blackout', the Ger+6 interpretation is acceptable, but what advantage is there over simply calling them bVI7? In classical harmony, the augmented sixth chords (especially the Italian and French +6s) cannot be explained any other way - indeed, that's why +6s were invented: to help make sense of something that could not make sense otherwise. But in pop harmony, even the most convincing +6 chords could easily be simplified to bVI7. With nothing to gain through employing +6s in pop harmony analysis, I see no reason to use them.

4 Comments

Many people have asked me about the band Cheap Trick, and they are mildly shocked when I say I'm not at all familiar. “They're so similar to The Beatles,” they enthuse, “you'd love them!” So the other day I listened to their self-titled 1977 debut album. And indeed they are similar to The Beatles! With this post, I'm launching a blog series on the comparison, starting with 'Mandocello', the ninth track of Cheap Trick. Here's a structural analysis and transcription: 0:00 Instrumental Intro 0:21 Riff and groove established 0:31 Verse 1 ("I can hear you laughing") 0:48 Verse 2 ("I will never leave you") 1:05 Instrumental Break 1:19 Verse 3 ("the thoughts you're thinking") 1:37 Verse 4 ("I can see you crying") 1:53 Abbreviated Instrumental Break 2:02 Bridge ("Look at me") 2:39 Abbreviated Verse 5 ("I can hear you thinking") 2:52 Verse 6 ("I'm the dream you're dreaming") 3:09 Terminus ("We can go down slowly") 3:37 Guitar Solo 3:47 Concluding Instrumental Verse 4:14 Instrumental Coda

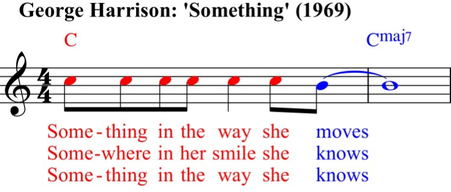

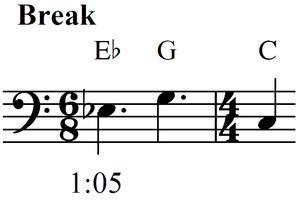

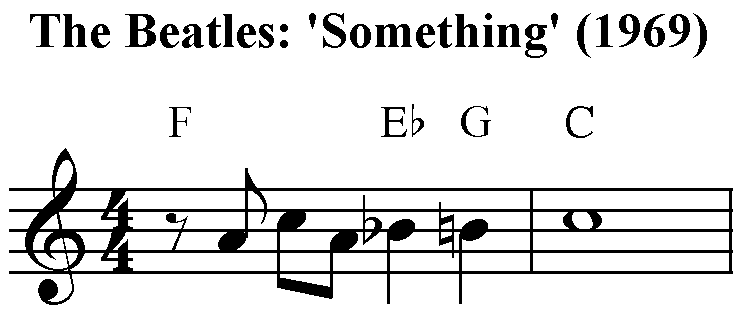

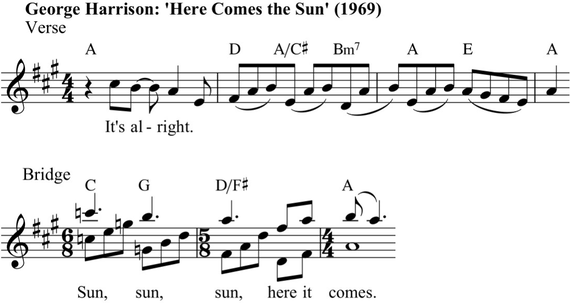

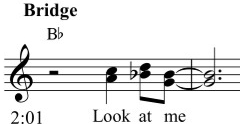

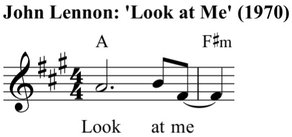

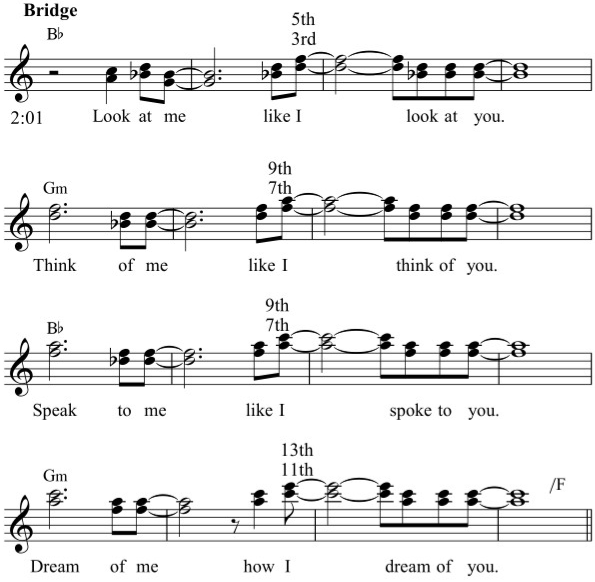

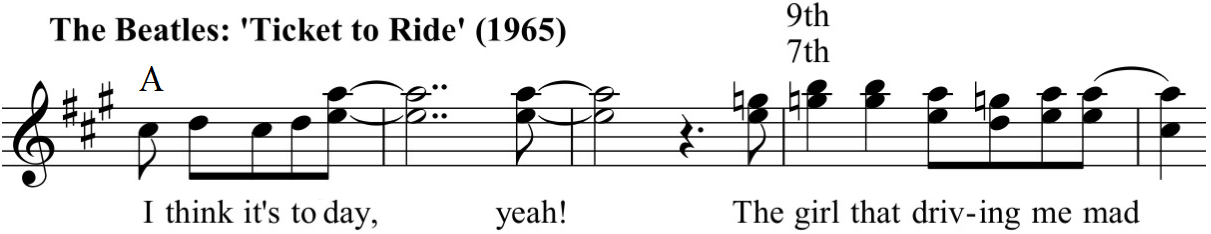

The first similarity I hear to a Beatles song is in the intro (and coda), where a C major chord (shown in red in the graphic below) moves to a CMM7 (shown in blue). This progression is heard four times in 'Mandocello' - twice during the intro and twice more during the coda. It's a pattern that has been used many times in other songs, including in the verses of George Harrison's 'Something'. Second, there is another similarity to 'Something': The first instrumental break of 'Mandocello' incorporates the peculiar progression Eb-G-C (bIII-V-I in C major), which is nearly identical to the famous opening riff in 'Something'. Third and most significantly, each verse of 'Mandocello' features a syncopated 5/4 bar (transformed into a 12/8 bar during the instrumental concluding verse) with a descending bass pattern and arpeggios... ...which bears a striking resemblance to Harrison's other song on Abbey Road, 'Here Comes the Sun'. Fourth and least significantly, the bridge of 'Mandocello' opens with the lyrics "look at me", which, coincidentally or otherwise, is also the title of a John Lennon song written in 1968 but not released until 1970 on his debut solo album John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band. The similarities, though modest, are still present - similar melodic contours and lyrical content. Given how familiar Cheap Trick was with The Beatles' output, it seems too close to be coincidence. I'm guessing this is conscious on Cheap Trick's part. Fifth and lastly, this "look at me" bridge employs progressive extended tertian vocal harmonies. The first phrase extends only to the 3rd and 5th; the second and third phrases extend to the 7th and 9th; and the fourth and climactic phrase of the section extends to the 11th and 13th. While not common, extended tertian vocal harmonies are significant in Beatles music, too. A good example can be heard in their 1965 song 'Ticket to Ride', which similarly builds up to a 7th and 9th above the root. So there are my thoughts on Cheap Trick's 'Mandocello'. I look forward to writing additional blogs comparing and contrasting with The Beatles as I listen through Cheap Trick's catalog.

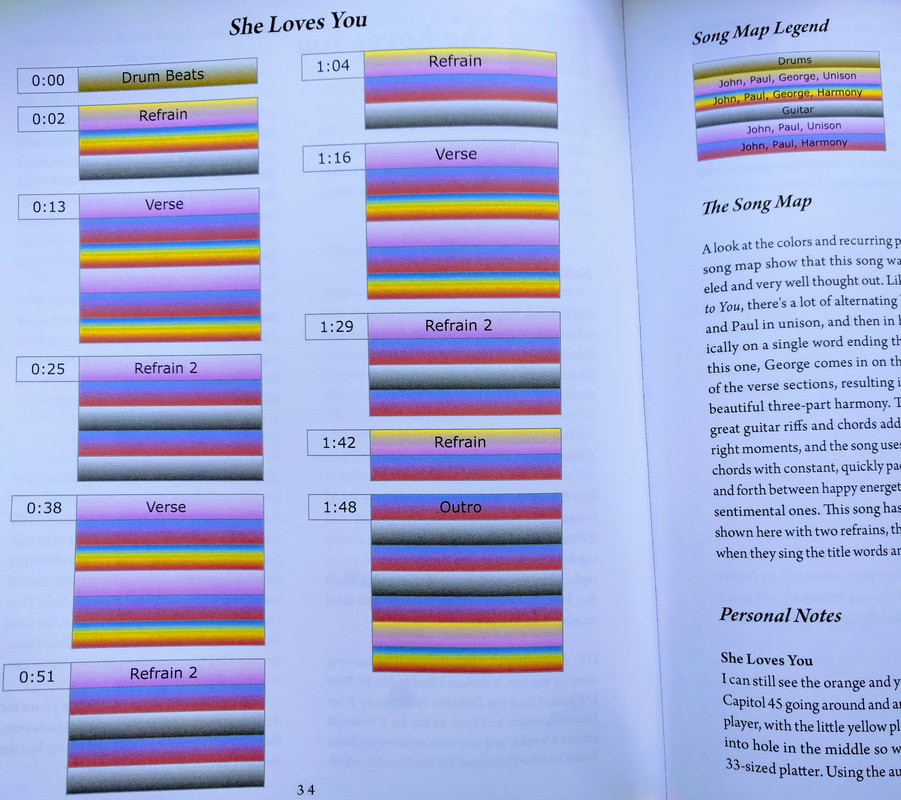

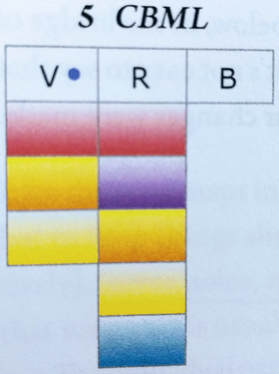

The other day I received an email from a man named Brian Hebert. He recently published a book titled Blue Notes and Sad Chords: Color Coded Harmony in The Beatles 27 Number 1 Hits, and offered to mail me a complementary copy. I eagerly accepted Brian's offer, but countered by saying he could save shipping costs by just giving it to me in person. Since he lives in Massachusetts, and I'm speaking throughout the Bay State this month, why don't we meet in person to chat and exchange books? So we set up a meeting on Wednesday, July 18 at Stone's Public House in Ashland, MA. A splendid time was guaranteed for all! Indeed, the conversation was so engaging that an hour and half passed in what felt like ten minutes! Brian told me all about his experiences writing the book, and how he made various decisions. I happily chimed in with my own stories - good and bad - of whole process. We also conversed about several of the notoriously difficult chords to identify: the intro of 'A Hard Day's Night', the B chord (is it major? minor? is there a seventh?) in 'I Want To Hold Your Hand'. At one point during the meal, I asked Brian if he'd be interested in a blog interview to help promote the book. He heartily agreed, and I hope to publish that shortly. After generously picking up the check, Brian left the restaurant with my BEATLESTUDY, volume 1: Harmonic Analysis of Beatles Music in hand; I departed with Blue Notes. And I've been carefully reading it for the last several days. Below is my summary and review. The book is divided into three parts. The first section is introductory, establishing the basic premises for the book. “Hundreds of books in all sizes and shapes have been written about the Beatles,” Hebert writes. “Many are biographical … some books are primarily collections of photographs. Still other books help readers peer behind the curtains … A small number of books actually describe the music in detail [my emphasis]" [page 4]. An author after my own heart! He continues: “Typically written by musical experts, most of these books require the reader to possess a detailed understanding of music theory and a very specialized vocabulary, and as such are generally inaccessible to the average fan. … One goal of this book is to bridge that gap, and provide lovers of Beatles music with a unique and enjoyable way to understand some of the key musical elements that made the four lads from Liverpool so successful, without needing to be a musician or possess any specialized knowledge of music theory. … One of the key ideas this book hopefully gets across is that these musical concepts can be conveyed and understood intuitively, using relatively simple, color-rich graphics, which do not at all require an in-depth understanding of music theory” (pages 4, 6). Hebert makes it clear this is not an academic textbook, though it is analytic in nature: “This book is not intended as a scholarly work. You won't find footnotes or a list of references, and Wikipedia has been used as a main source for many facts” (page 12). The second section features color-coded “song map” textural analyses of The Beatles' 27 #1 hits (as included on the album 1), or in his own words, “the song maps show which Beatles are singing on the different parts of a song, and whether they are singing alone or together, in unison or in harmony” (page 3). In other words, the colors represent who is singing what. “If we assign a primary color to each singing Beatle voice (John red, Paul blue, and George yellow) and color code the parts of a song, we can see where they were singing alone, using a primary color, or together in unison or harmony, using secondary colors” (page 8). 'She Loves You' is a particularly vibrant example: Because the combinations of voices in this song are so varied (see the song map legend at the top right of the graphic), the song map's coloration is equally varied. The third and final section, for which the book is titled, analyzes harmony through a new color scheme, “using the analogy of an artist's palette of paints” (page 3). In this case, color represents not texture but harmony: red for I, green for ii, light gray for bIII, purple for iii, orange for IV, yellow for V, dark gray for bVI, light blue for vi, dark blue for bVII, and beige for vii. In general, brighter colors correspond to happier-sounding chords, where darker colors correspond to sadder-sounding chords. Here, for example, is the palette for 'Can't Buy Me Love': What this palette shows is that the verses employ the bright-sounding I (red), IV (orange), and V (yellow), while the refrains supplement with the dark-sounding iii (purple), and vi (blue). I've always found 'Can't Buy' fascinating for precisely this reason: The verses sound much happier than the refrains (what I would call choruses, but that's semantics and I won't get into it here). Furthermore, the lyrics reinforce this shift. In the darker-sounding refrains, the lyrics are negative, with Paul describing what cannot be done (“Can't buy me love...”). But in the brighter-sounding verses, the lyrics are more positive, describing what can be done (“I'll buy you a diamond ring...”, “I'll give you all I've got...”). Also, observant readers might notice a little blue dot in the above graphic, just to the right of the “V”. This indicates the use of a “blue note”, in which the pitch of a tone is lowered (ie, in a C major chord, the note E would be “normal”, while the note E-flat would be a “blue” note) for expressive reasons. “They can give a low-down, swampy, or lonesome feeling,” writes Hebert [page 17]. In the verses of 'Can't Buy', for instance, Paul frequently sings blue notes: “I'll buy you a dia-mond ring..”, “I'll get you a-ny-thing...”, “I'll give you all I got...”, “I may not have a lot...”, “Say you don't need no diamond rings...”, “Tell me that you want the kind of things...”. The Beatles (and a great many other pop musicians) use blue notes frequently. Where my own work (especially in the last year or two) has turned more analytic and technical, Hebert's Blue Notes and Sad Chords provides an accessible path for the obsessive but non-musician fan who wants to better understand the intricacies and sophistication of The Beatles' extraordinary music. And in addition to the colorful analytics, Hebert balances things out by including lots of non-technical nostalgic info, like calling out other artist’s songs in the charts before and after a Beatles hit, a back story for each number, personal memories and thoughts about the Beatles and the 1960s, and a condensed Beatles timeline. While I'm not a first-generation fan, I imagine the book could be a very pleasurable trip down memory (Penny?) lane for anybody that lived through the Sixties. As the book's back cover states: “Whether you're a long-time baby boomer Beatle fan, a younger newcomer, or somewhere in between, this book will give you an entirely new appreciation for the most amazing band ever.”

Blue Notes and Sad Chords is available for purchase on Amazon.com. |

Aaron Krerowicz, pop music scholarAn informal but highly analytic study of popular music. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed