|

In the third semester of undergraduate music theory (which I'll be teaching this fall), we cover modal mixture, the Neapolitan chord, and augmented sixth chords, among other topics. I've kept an eye out for any pop music that employs all three so I can use it on an exam, and I've finally found the perfect example: Zelda's theme by Koji Kondo.

2 Comments

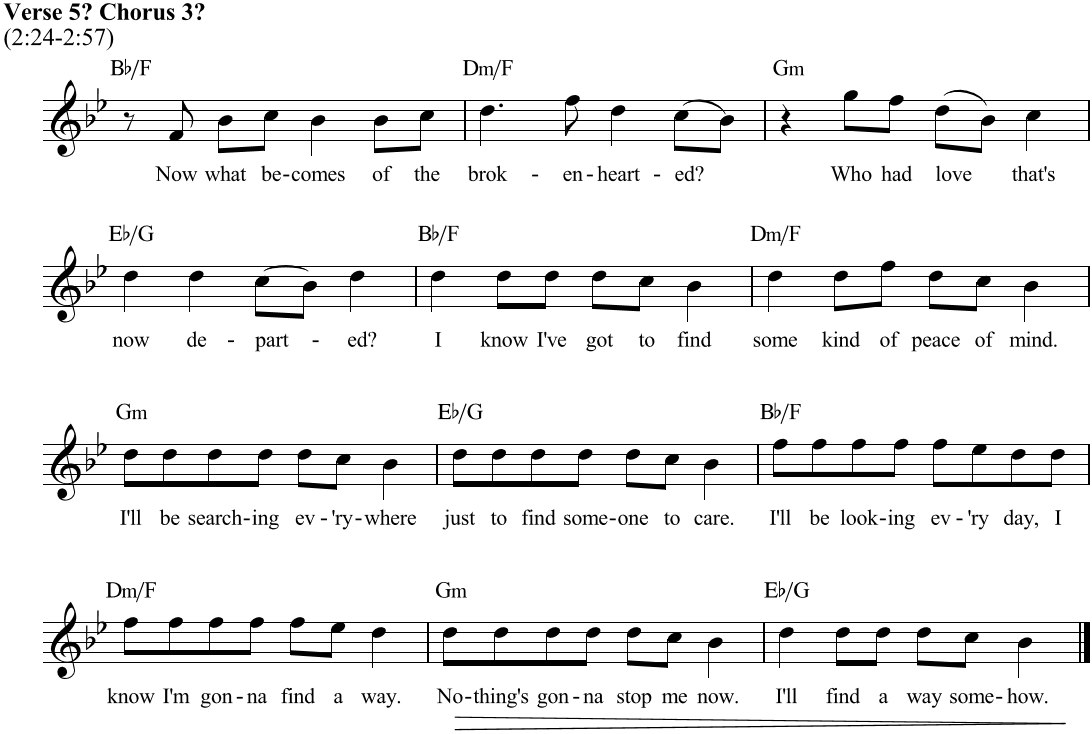

I've heard Jimmy Ruffin's 1966 classic hit 'What Becomes of the Brokenhearted' dozens of times, but until recently I had never listened terribly closely.

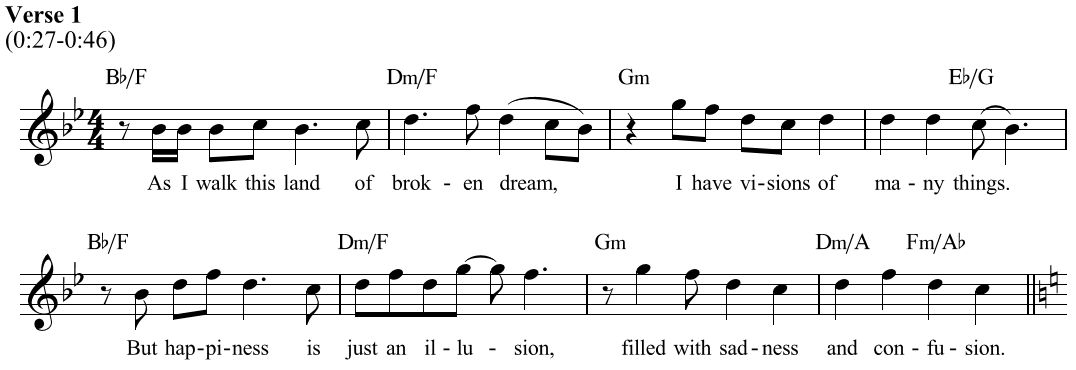

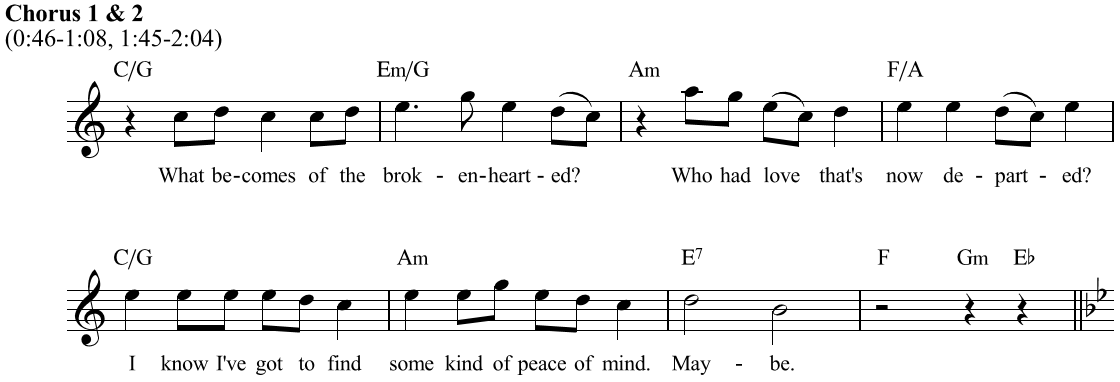

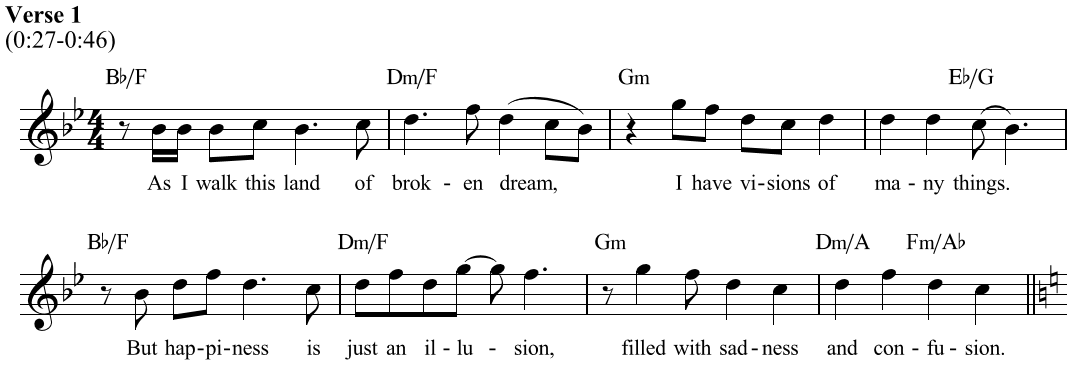

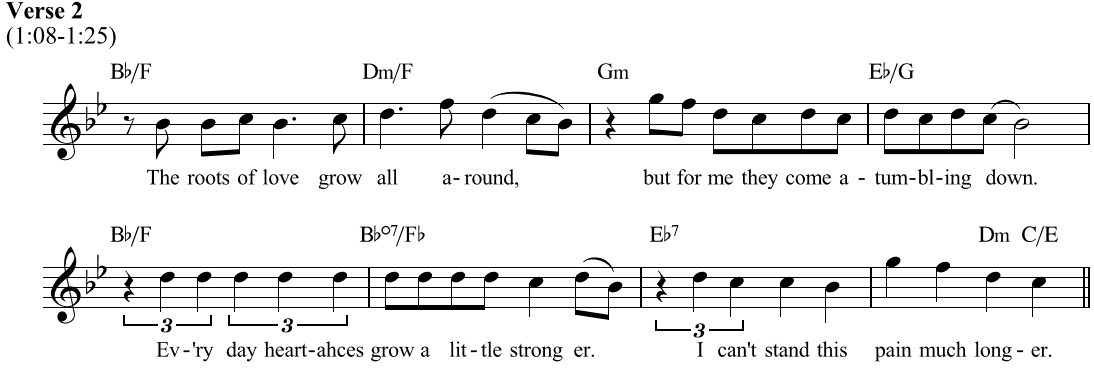

The first thing that stands out to me, and the reason I started analyzing in the first place, are the key changes: The verses are all in Bb major, while the first two choruses are in C major. Each modulation is executed via a pivot chord. Despite the differences in tonality, however, the chords progressions are identical (I64|iii6|vi|IV6|I64) for the first five bars of each section. These tonalities are clear, even though the bass line undermines almost all of the chords by almost never playing the root - most of the time it plays the third or fifth, the instability of which reflects the theme of unrequited love found in the lyrics. I have been unable to verify who the bass player is on this record, but I'm guessing it's James Jamerson, who used this lack-of-root trick frequently (see The Four Tops' 'Reach Out' for a another particularly good example). The form is also particularly interesting: 0:00-0:27 Intro (based on Verse 2) Bb major 0:27-0:46 (A) Verse 1 Bb major 0:46-1:08 (B) Chorus 1 C major 1:08-1:25 (A') Verse 2 Bb major 1:25-1:45 (A) Verse 3 Bb major 1:45-2:04 (B) Chorus 2 C major 2:04-2:24 (A') Verse 4 Bb major 2:24-2:57 (A/B?) Verse 5/Chorus 3? Bb major There are two distinct but clearly related verses. Verses 1 and 3 are labeled (A); verses 2 and 4 are labeled (A'). They differ only in their last three measures. The reason for this discrepancy is tonal: the (A) verses segue to the C major chorus, while the (A') verses stay in Bb. Interspersed with these verses is the chorus (B), resulting in a rather unusual ABA'ABA'(A/B) form, with an ambiguous final section that is either the fifth verse or third chorus, depending on interpretation. The ambiguity stems from a conflict between the tonality and the lyrics. The tonality of this final section is Bb major, implying it's a verse; but the lyrics are the same as those heard in the two previous choruses, implying it's a chorus. (And since, as pointed out above, the chord progressions are the same for both the verse and chorus, that provides no clarity as this final section merely repeats the first four measures while fading out.) Many songs feature a tonal conflict in which two or more keys are juxtaposed in a battle for supremacy. Though there are instances where two or more keys exist in equilibrium, with neither/none more rhetorically important than the other(s) (The Beatles' 'Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!' might be the best such example), but most often one key reigns supreme - and it's usually the key of the chorus, as opposed to the key of the verse or bridge, because the chorus is usually the focal point of the song. But every once in while there's a song where the chorus surrenders its tonal supremacy by capitulating in its final iteration to the verse's key (The Beatles' 'Penny Lane', for instance). And that's what happens in 'Brokenhearted', which was released one year prior to 'Penny Lane'. Without this ambiguous final section, I'd be inclined to proclaim the choruses' C major as the primary tonic, with the verses' Bb major as a secondary. But since this final section employs the chorus lyrics with the verse tonality, I am forced to switch that opinion: Bb is actually the primary tonic, with C major riding shotgun.

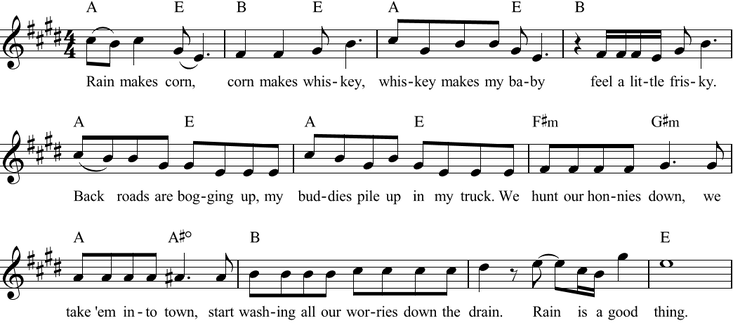

I went to the Indianapolis Indians minor league baseball game last night, in large part to see two high-ranked prospects pitch against each other: the home team's Mitch Keller (the Pittsburgh Pirates #1 prospect, and baseball's #17 overall) vs. the Louisville Bats' Vladamir Gutierrez (the Cincinnati Reds' #7 prospect). In the top of the 8th inning, Mother Nature halted play with rain. Check out this photo, which I borrowed from the Indians' official Twitter account: During the break, they played a handful of precipitation-themed songs, such as B.J. Thomas' Raindrops are Falling on My Head' (1969). As a pop music scholar and music theory teacher, I'm constantly on the lookout (hearout?) for pieces that I can use as examples in my classes, and three other tunes played last night work perfectly. In order of sophistication: 1. Luke Bryan's 'Rain is a Good Thing' (2009)... ... employs a secondary diminished chord (vii°/V) at the end of each chorus (on the word "town"). 2. Jimmy Nash's 'I Can See Clearly Now' (1972)... ... employs mode mixture by using C major (bVII) and F major chords (bIII) in D major. (Also a chromatic C# minor in the bridge, though that's not as good an example since it'd have to borrow from the parallel Lydian instead of the parallel minor.)

3. Milli Vanilli's 'Blame it on the Rain' (1989)... ... modulates constantly. The intro, prechorus, and first two choruses are all in B major; the verses are in B-flat major; the bridge is ambiguous but it sounds like A-flat major to my ears; and the final chorus and coda are in C major. It's not at all unusual for songs to change keys, but there aren't too many out there that do so three distinct times. Also highly unusually, NONE of these tonalities are closely related, which makes this an ideal example for the chapter I'll be teaching this fall on distantly-related modulation.

Maybe rain delays aren't so bad after all... :-)

The past few days I've blogged of the permanent Picardy third in Linkin Park's 'Somewhere I Belong' and 'Easier to Run', citing them as the first two songs that thoroughly convince me of the technique. But after thinking about it for a while, I realized that's not entirely true. Alanis Morisette's 'You Ought Know', from her 1995 mega-hit album Jagged Little Pill is equally convincing:

The song is clearly in F# minor - I don't see how anybody could argue otherwise - and yet the chorus consistently employs an F# major triad. It's also an excellent song to demonstrate mode mixture on IV, so I'll be using this as a homework assignment for my sophomore theory class this fall, when we get to the chapter on mode mixture.

|

Aaron Krerowicz, pop music scholarAn informal but highly analytic study of popular music. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed