|

The Led Zeppelin song that displays the most different influences has to be 'How Many More Times', the concluding track of their 1969 self-titled debut album. Jimmy Page never denied those influences, admitting the song "was made up of little pieces I developed when I was with the Yardbirds. ... After the Yardbirds fell apart and it came time to create Zeppelin, I had all those ideas as a textbook to work from" (Tolinski, page 82, 50). Robert Plant never hid it, either, saying, "it's got all those Sixties bits and pieces" (Wall, page 50). This blog will observe each "little piece" to illustrate how 'How Many More Times' came together. The most obvious influence is Howlin' Wolf's 'How Many More Years' (1951), which shares a nearly-identical title and modest lyrical similarities. Howlin' Wolf: 'How Many More Years' (0:26-0:51) How many more years have I got to let you dog me around? How many more years have I got to let you dog me around? I'd as soon rather be dead, sleeping six feet in the ground Led Zeppelin: 'How Many More Times' (0:40-1:18, 7:11-7:47) How many more times, treat me the way you wanna do How many more times, treat me the way you wanna do When I give you all my love, please, please be true ... How many more times, barrel house all night long How many more times, barrel house all night long Well I've got to get to you, baby, oh, please come home Another lyrical influence is Albert King's 'The Hunter': Albert King: 'The Hunter' (0:14-0:56) They call me the hunter, that's my name A pretty woman like you, is my only game I bought me a love gun, just the other day And I aim to aim it your way Ain't no use to hide, ain't no use to run 'Cause I've got you in the sights of my love gun Led Zeppelin: 'How Many More Times' (6:17-7:05) Well, they call me the hunter, that's my name Call me the hunter, that's how I got my fame Ain't no need to hide, ain't no need to run 'Cause I've got you in the sights of my gun Zeppelin biographer Stephen Davis claims it also borrows riffs from King's song (Davis, page 59), but I don't hear any. Author Keith Shadwick also claims the "sledgehammer walking riff" was "borrowed from Albert King's 'The Hunter'" (Shadwick, page 59). But since neither Davis nor Shadwick provides any evidence to support or validate the claim, I'm confident dismissing it as nonsense. Less obvious, but still significant, Plant also borrowed from 'Kisses Sweeter Than Wine' (1957) by Jimmie Frederick Rodgers (not to be confused with country singer Jimmie Charles Rodgers). Jimmie F. Rodgers: 'Kisses Sweeter Than Wine' (0:01-0:25, 1:20-1:42) Well, when I was a young man never been kissed I got to thinkin' it over how much I had missed So I got me a girl and I kissed her and then, and then Oh, lordy, well I kissed her again Because she had kisses sweeter than wine ... Well our children they numbered just about four And they all had a sweetheart a-knockin' on the door They all got married and they wouldn't hesitate I was, whoops oh lord, the grandfather of eight Because she had kisses sweeter than wine Led Zeppelin: 'How Many More Times' (4:08-4:48) I was a young man, I couldn't resist Started thinkin' it over, just what I had missed Got me a girl and I kissed her and then and then Whoops, oh lord, well I did it again Now I've got ten children of my own I got another child on the way that makes eleven Once again, there appears to be some confusion whether or not Rodgers' influence was also musical. Another Zep biographer, Mick Wall, claims, "there was even a lick of two appropriated from Jimmy [sic] Rodgers' 'Kisses Sweeter Than Wine'" (Wall, page 55). But here again, I do not hear any significant musical similarities, and since Wall provides no evidence to support his statement, I cannot agree with the conclusion. So if neither King or Rodgers served as musical inspiration for 'How Many More Years', then who did? Five years before Zeppelin released 'How Many More Times', The T-Bones released the same song. Wall claims Zep's version has "more than a passing nod to a mid-Sixties version of the same tune by Gary Farr and the T-Bones (Wall, page 55), but to my ears "a passing nod" is generous. Rather, the most significant thing to notice here is that The T-Bones changed the original title of 'How Many More Years' to 'How Many More Times' - an alteration that Zeppelin would retain. Much more significant are things Zeppelin does differently from The T-Bones. The cover opens with a repeated two-measure riff absent from The T-Bones' recording... ... but present in a 1965 Yardbirds cover of Howlin' Wolf's 'Smokestack Lightning'. Though The Yardbirds never released a studio recording of 'Smokestack Lightning', at least three live recordings have been released:

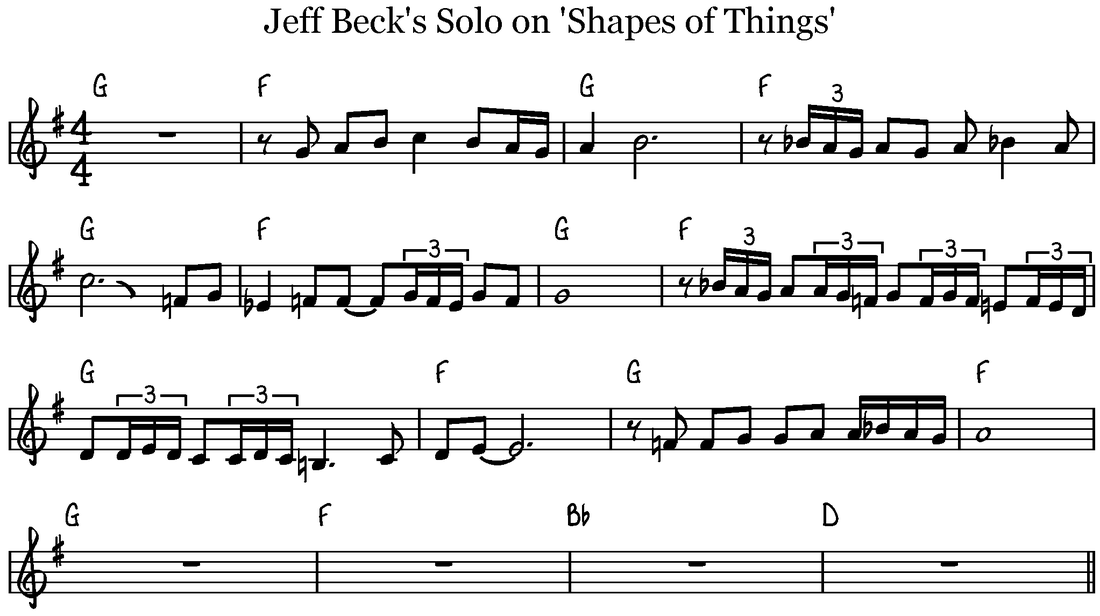

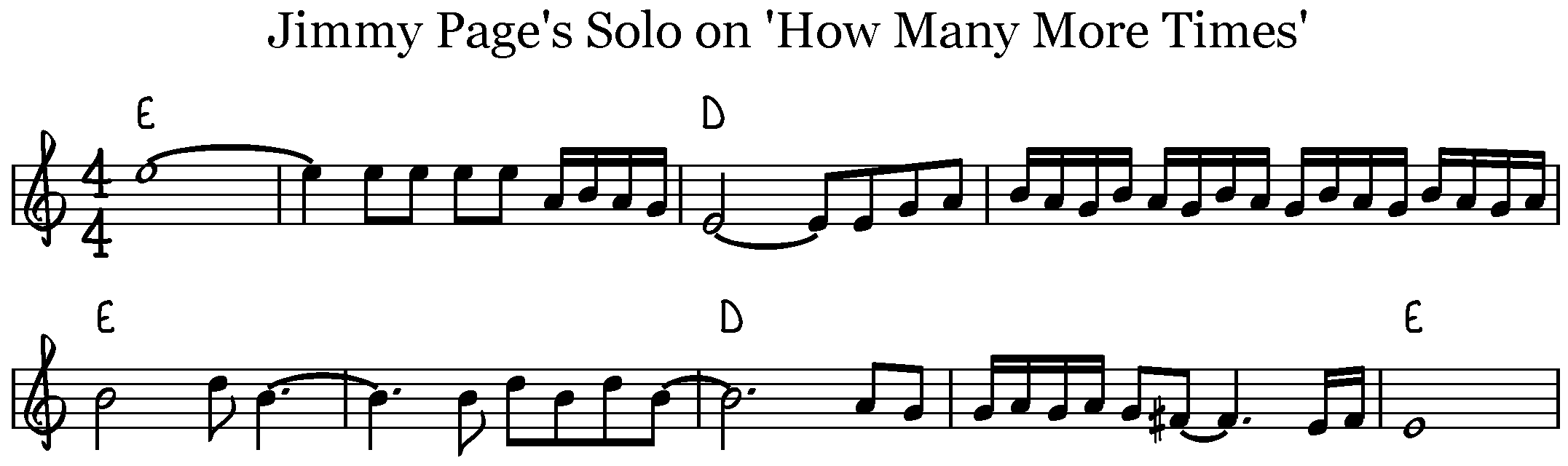

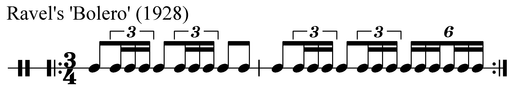

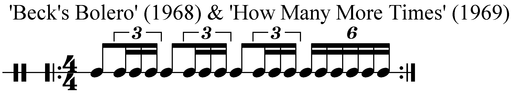

Of those three, only the last employs the riff to be recycled on 'How Many More Years'. Eric Clapton joined The Yardbirds in October 1963, and quit in March 1965. Presumably that means the first two recordings - the ones WITHOUT the 'How Many More Years' riff - feature him on guitar. Jeff Beck joined in March 1965, and quit in the fall of 1966. Presumably that third recording - the one WITH the riff - features him on guitar. So Beck might have written it, or perhaps he, in turn, borrowed it from someone else. Either way, the 'How Many More Years' riff was NOT invented by Jimmy Page. More confusion is found regarding Page's solo on 'How Many More Times'. Wall claims Page's solo is "a slowed-to-a-crawl take on Jeff Beck's solo from the Yardbirds' 'Shapes of Things' (Wall, page 55), and Davis insists "the guitar solo is from 'Shapes of Things' (Davis, page 59). But is that true? And if so, how? Here's Beck's solo from 'Shapes' (starting at 1:34): And here's the beginning of Page's solo from 'More Times' (starting at 2:11): To my ears, the only similarity is the I-bVII harmonic ostinato (|G|F| in 'Shapes'; |E| |D| | in 'More Times'). I hear no significant similarities between the actual solos. There is one more musical similarity: The bolero rhythm. French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) is most famous for his 1928 composition 'Bolero', which features this rhythmic ostinato throughout: After departing The Yardbirds in 1966, Jeff Beck launched a solo career. His 1968 debut solo album, Truth, includes the track 'Beck's Bolero', which incorporates a similar rhythmic ostinato. One year later, Jimmy Page (who produced and performed on 'Beck's Bolero') and John Paul Jones (who also performed on 'Beck's Bolero') would incorporate an identical rhythmic ostinato into 'How Many More Years'. SOURCES

Davis, Stephen. 1995. Hammer of the Gods: Led Zeppelin Unauthorized. Pan Books, an imprint of Macmillan General Books; London, England. Shadwick, Keith. 2005. Led Zeppelin: The Story of a Band and their Music 1968-1980. Backbeat Books; London, England. Tolinski, Brad. 2012. Light & Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page. Crown Publishers; New York, NY. Wall, Mick. 2008. When Giants Walked the Eart: A Biography of Led Zeppelin. St. Martin's Griffin; New York, NY.

0 Comments

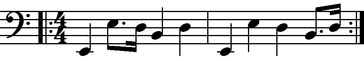

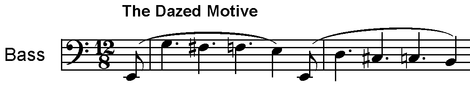

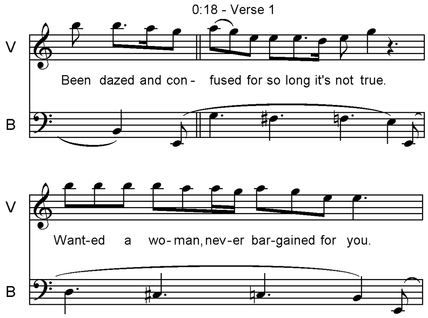

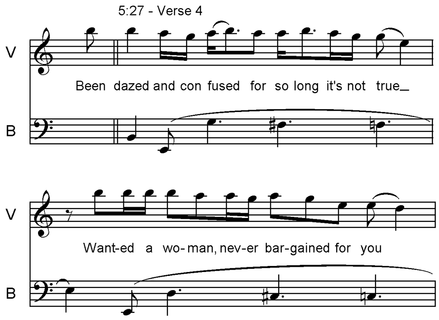

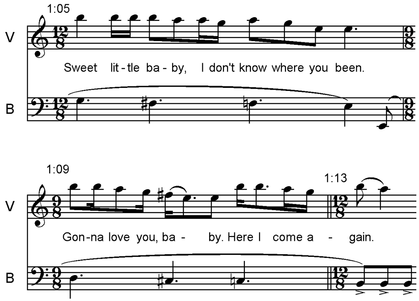

It's no secret that Led Zeppelin loves playing with rhythm. And one of their favorite stunts is establishing a rhythmic expectation early in a song, then thwarting that expectation later through a compositional technique known as rhythmic displacement. I have several examples in mind, and I'll dedicate one blog for each. To start, let's look at “Dazed and Confused”, the fourth track of Zeppelin's self-titled debut album from 1968. The first thing heard on the track is John Paul Jones' bass playing two measures, each consisting of four chromatically descending tones, and each with an anacrusis - what I'll call “The Dazed Motive” due to its rather wobbly feel. That Dazed motive is heard a total of 16 times. The first eight instances (heard consecutively from 0:00-1:13) all start on beat one, as illustrated above. But the last eight instances (heard four times from 1:21-1:57, and another four times from 5:11-5:45) all displace the motive one full beat – they all start on beat two, as illustrated below. But it's not just Jones' bass that is displaced – it's Robert Plant's vocals, as well. At first, Plant places the syllable “fused” from “confused” on the downbeat (0:18), delineating the official start of the first verse. And he does the same phrasing (but with different lyrics) with the second verse (0:55). But with verses three and four, his entry is delayed one beat. Since verse 4 begins with the same lyrics as verse 1, it makes for an ideal apples-to-apples comparison. Additionally, Jimmy Page's guitar is also displaced one beat. I won't provide examples for that, however, since it's identical to Jones' bass. In fact, the only instrument not displaced is John Bonham's drums. And it's the percussion that confirms that a displacement has indeed happened. Because obviously if the drums were displaced one beat, just like every other instrument, then this would be a case of changing meters – not displacement. Since changing meters is another favorite rhythmic technique of Zeppelin, it's slightly surprising that we don't find more meter changes in “Dazed and Confused”. Their rhythmic instability could be put to good use in a song with this title. And yet, there are just two instances of measure(s) in a meter other than 12/8. The more obvious instance comes during the up-tempo middle section, from 3:30-5:02, where a metric modulation of eighth=quarter yields a fast 4/4 meter. The less obvious but more significant instances comes at the end of the second verse (1:09), which is abbreviated by one beat from a 12/8 bar (as it was in verse 1) to a 9/8. After this single measure of 9/8, the pitched instruments are consistently displaced while the drums are not. So this 9/8 measure might be thought of as the catalyst for the subsequent rhythmic displacement. And it's for that reason that this 9/8 measure is my personal favorite measure in the entire song :-)

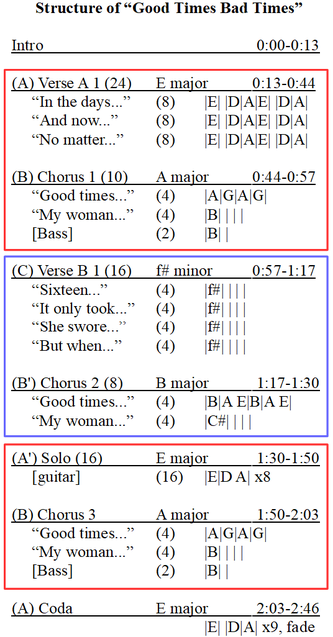

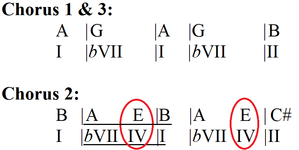

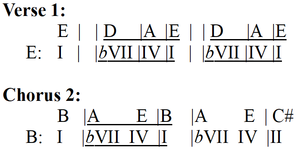

I started the analytical (as opposed to the introductory) part of the blog yesterday with a structural analysis of “Whole Lotta Love”. In it, I implied that early Zeppelin songs illustrate how they grew out of their predecessors like The Beatles. That is true to a certain extent, but that's not entirely true. I oversimplified a bit. Of course there are exceptions. And as evidence to the contrary, I present a structural analysis of “Good Times Bad Times”, the opening number of Zeppelin's 1968 self-titled debut album, which has a unique (to my knowledge, anyway) formal design. Get a load of this oddity!: Okay, so, the first thing to notice is that there are two distinct verses, here labeled Verse A and Verse B. While The Beatles occasionally employed multiple different verses within the same song (check out “Glass Onion” or “Lovely Rita”), it's rare. I don't know other bands' oeuvres well enough to cite a non-Beatles example off the top of my head, but I'm sure there are examples to be found. Some scholars have debated with me over the justification for using multiple verses instead of other labels. “Rita”, for example, is often analyzed as using verses and bridges instead of multiple verses. I certainly see the point, but I maintain these are all verses for reason I won't get into here. In any case, “Good Times” definitely uses multiple verses because each section in question is paired with a chorus – exactly what would be expected of verses. The second thing that stands out is that the chorus also has two different iterations. The distinction here is harmonic: The first and third choruses are in A major, while the second is in B major. This middle chorus grows organically out of what was heard in the first chorus as it adds an E chord (IV) on the third beats of the second and fourth measures, circled red in the example below. This addition results in a double plagal cadence (A-E-B, bVII-IV-I, underlined below) from the second to third measures. This ties in to the harmony of the initial verse (shown in the example below), which also employs double plagals but in E major (D-A-E) and twice as long (four measures where the same pattern in the chorus lasts only two). Also, the middle chorus elucidates the tonality of the outer choruses. The first and third choruses are harmonically ambiguous on their own – are they really in A major? We don't necessarily have enough information to make that claim - there are no cadences to confirm such a conclusion. But the addition of those double plagals in the middle chorus implies that the harmony of the first and third can be interpreted as “incomplete double plagal cadences” which are missing the IV chord. With that in mind, we can indeed infer that the outer choruses are in A major.

One last thing about the choruses: The middle iteration is abbreviated. While the first and third choruses both feature a two-bar bass transition, the second chorus omits it. This further differentiates the choruses, which strengthens the eventual conclusion (see below) that "Good Times" is a compound ternary structure. Finally, the solo replaces a verse. It employs identical harmonies, but rhythmically halved. This, too, grows organically out of what preceded it. The solo also uses double plagal cadences, just like the first verse and second chorus. It uses the tonality of the verse's double plagals (D-A-E) but with the chorus's rhythms (two measures instead of four). So the solo is related to both the first verse (through tonality) and to the second chorus (through rhythm). The overall structure of “Good Times Bad Times”, then, is a hybrid AB|CB'|A'B – it's part compound simple (an AB x3 in which the middle AB is actually a CB') and part compound ternary (ABA'). If I had to pick one of those designations, I think the latter more accurately and precisely articulates the form. Even though this song is from Zep's first album, it shows a spectacularly advanced hybrid formal structure and organic development that breaks with their predecessors' work (to the extent of my knowledge). It certainly would not be the last time they would use such a sophisticated musical design. |

Aaron Krerowicz, pop music scholarAn informal but highly analytic study of popular music. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed