|

Macro Structure: Compound ternary (ABA) PART A 0:00-0:32 Intro (15) 0:32-0:56 (A) Verse A 1 (12) 0:56-1:44 (A') Verse A 2 + Refrain (24) PART B 1:44-1:54 Unison 2-bar riff x2 (4) 1:54-2:04 Harmonized 2-bar riff x2 (4) 2:04-2:18 (B) Verse B 1 + 2-Bar Refrain (6) 2:18-2:37 (B') Verse B 2 + 4-Bar Refrain (8) 2:37-2:47 Unison 2-bar riff x2 (4) 2:47-2:57 Harmonized 2-bar riff x2 (4) 2:57-3:11 (B) Verse B 3 + 2-Bar Refrain (6) 3:11-3:30 (B') Verse B 4 + 4-Bar Refrain (8) 3:30-3:40 Unison 2-bar riff x2 (4) 3:40-3:52 Harmonized 2-bar riff x2 (4) PART A 3:52-4:19 (A'') Refrain (8)

There's the raw analysis. I'll post commentary on that analysis soon.

0 Comments

The Led Zeppelin song that displays the most different influences has to be 'How Many More Times', the concluding track of their 1969 self-titled debut album. Jimmy Page never denied those influences, admitting the song "was made up of little pieces I developed when I was with the Yardbirds. ... After the Yardbirds fell apart and it came time to create Zeppelin, I had all those ideas as a textbook to work from" (Tolinski, page 82, 50). Robert Plant never hid it, either, saying, "it's got all those Sixties bits and pieces" (Wall, page 50). This blog will observe each "little piece" to illustrate how 'How Many More Times' came together. The most obvious influence is Howlin' Wolf's 'How Many More Years' (1951), which shares a nearly-identical title and modest lyrical similarities. Howlin' Wolf: 'How Many More Years' (0:26-0:51) How many more years have I got to let you dog me around? How many more years have I got to let you dog me around? I'd as soon rather be dead, sleeping six feet in the ground Led Zeppelin: 'How Many More Times' (0:40-1:18, 7:11-7:47) How many more times, treat me the way you wanna do How many more times, treat me the way you wanna do When I give you all my love, please, please be true ... How many more times, barrel house all night long How many more times, barrel house all night long Well I've got to get to you, baby, oh, please come home Another lyrical influence is Albert King's 'The Hunter': Albert King: 'The Hunter' (0:14-0:56) They call me the hunter, that's my name A pretty woman like you, is my only game I bought me a love gun, just the other day And I aim to aim it your way Ain't no use to hide, ain't no use to run 'Cause I've got you in the sights of my love gun Led Zeppelin: 'How Many More Times' (6:17-7:05) Well, they call me the hunter, that's my name Call me the hunter, that's how I got my fame Ain't no need to hide, ain't no need to run 'Cause I've got you in the sights of my gun Zeppelin biographer Stephen Davis claims it also borrows riffs from King's song (Davis, page 59), but I don't hear any. Author Keith Shadwick also claims the "sledgehammer walking riff" was "borrowed from Albert King's 'The Hunter'" (Shadwick, page 59). But since neither Davis nor Shadwick provides any evidence to support or validate the claim, I'm confident dismissing it as nonsense. Less obvious, but still significant, Plant also borrowed from 'Kisses Sweeter Than Wine' (1957) by Jimmie Frederick Rodgers (not to be confused with country singer Jimmie Charles Rodgers). Jimmie F. Rodgers: 'Kisses Sweeter Than Wine' (0:01-0:25, 1:20-1:42) Well, when I was a young man never been kissed I got to thinkin' it over how much I had missed So I got me a girl and I kissed her and then, and then Oh, lordy, well I kissed her again Because she had kisses sweeter than wine ... Well our children they numbered just about four And they all had a sweetheart a-knockin' on the door They all got married and they wouldn't hesitate I was, whoops oh lord, the grandfather of eight Because she had kisses sweeter than wine Led Zeppelin: 'How Many More Times' (4:08-4:48) I was a young man, I couldn't resist Started thinkin' it over, just what I had missed Got me a girl and I kissed her and then and then Whoops, oh lord, well I did it again Now I've got ten children of my own I got another child on the way that makes eleven Once again, there appears to be some confusion whether or not Rodgers' influence was also musical. Another Zep biographer, Mick Wall, claims, "there was even a lick of two appropriated from Jimmy [sic] Rodgers' 'Kisses Sweeter Than Wine'" (Wall, page 55). But here again, I do not hear any significant musical similarities, and since Wall provides no evidence to support his statement, I cannot agree with the conclusion. So if neither King or Rodgers served as musical inspiration for 'How Many More Years', then who did? Five years before Zeppelin released 'How Many More Times', The T-Bones released the same song. Wall claims Zep's version has "more than a passing nod to a mid-Sixties version of the same tune by Gary Farr and the T-Bones (Wall, page 55), but to my ears "a passing nod" is generous. Rather, the most significant thing to notice here is that The T-Bones changed the original title of 'How Many More Years' to 'How Many More Times' - an alteration that Zeppelin would retain. Much more significant are things Zeppelin does differently from The T-Bones. The cover opens with a repeated two-measure riff absent from The T-Bones' recording... ... but present in a 1965 Yardbirds cover of Howlin' Wolf's 'Smokestack Lightning'. Though The Yardbirds never released a studio recording of 'Smokestack Lightning', at least three live recordings have been released:

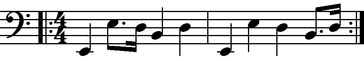

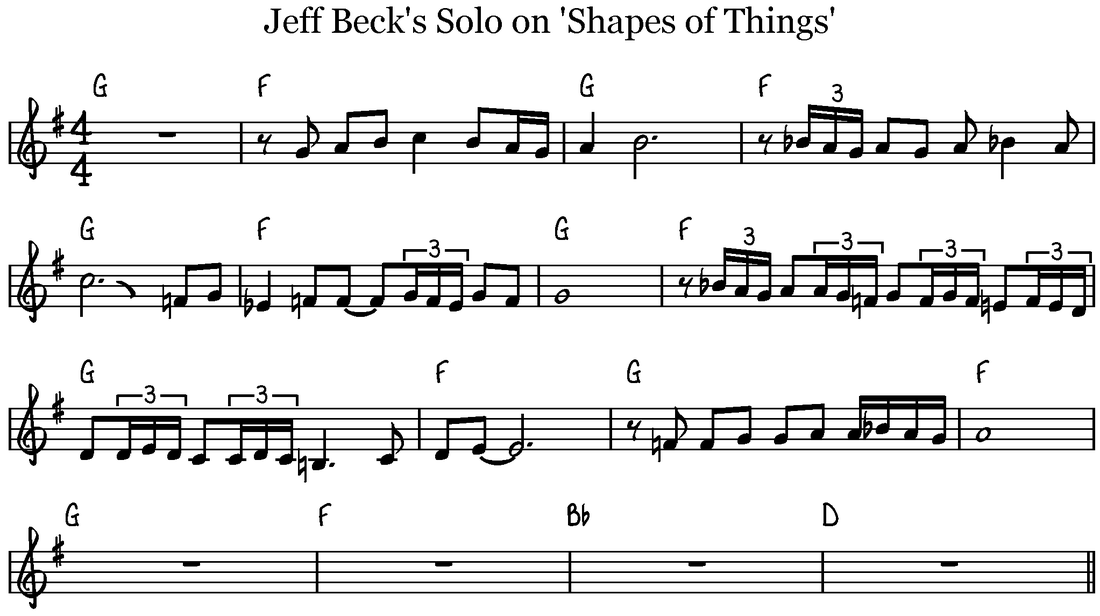

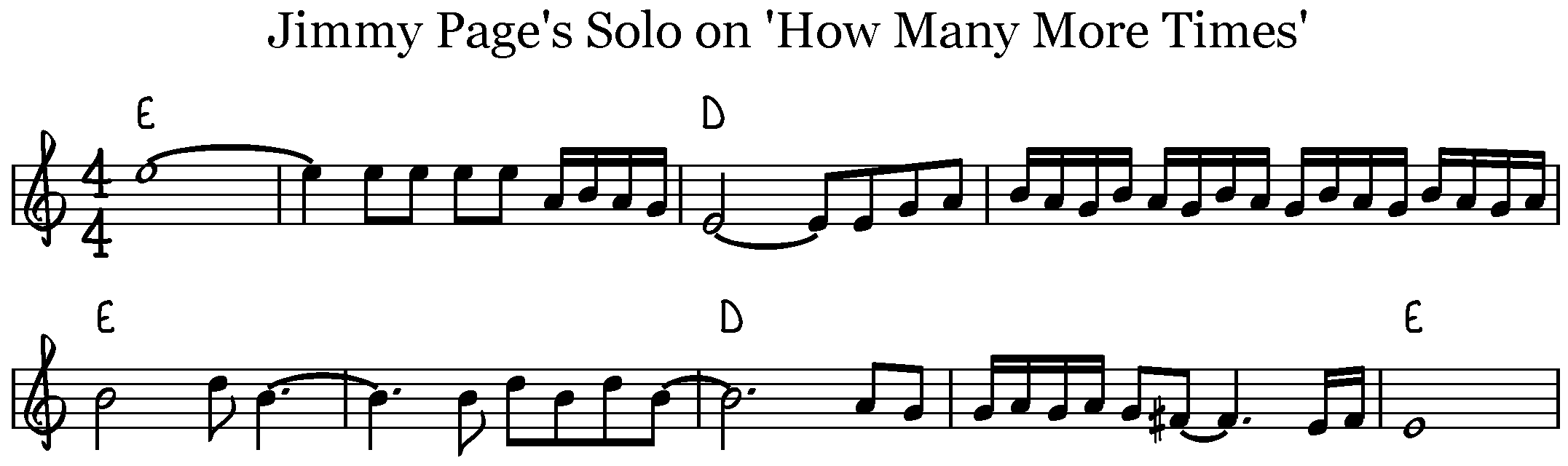

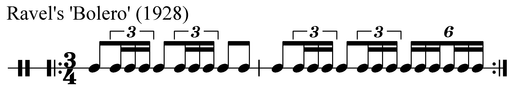

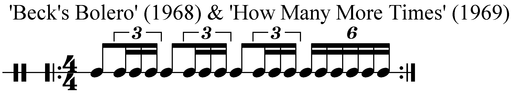

Of those three, only the last employs the riff to be recycled on 'How Many More Years'. Eric Clapton joined The Yardbirds in October 1963, and quit in March 1965. Presumably that means the first two recordings - the ones WITHOUT the 'How Many More Years' riff - feature him on guitar. Jeff Beck joined in March 1965, and quit in the fall of 1966. Presumably that third recording - the one WITH the riff - features him on guitar. So Beck might have written it, or perhaps he, in turn, borrowed it from someone else. Either way, the 'How Many More Years' riff was NOT invented by Jimmy Page. More confusion is found regarding Page's solo on 'How Many More Times'. Wall claims Page's solo is "a slowed-to-a-crawl take on Jeff Beck's solo from the Yardbirds' 'Shapes of Things' (Wall, page 55), and Davis insists "the guitar solo is from 'Shapes of Things' (Davis, page 59). But is that true? And if so, how? Here's Beck's solo from 'Shapes' (starting at 1:34): And here's the beginning of Page's solo from 'More Times' (starting at 2:11): To my ears, the only similarity is the I-bVII harmonic ostinato (|G|F| in 'Shapes'; |E| |D| | in 'More Times'). I hear no significant similarities between the actual solos. There is one more musical similarity: The bolero rhythm. French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) is most famous for his 1928 composition 'Bolero', which features this rhythmic ostinato throughout: After departing The Yardbirds in 1966, Jeff Beck launched a solo career. His 1968 debut solo album, Truth, includes the track 'Beck's Bolero', which incorporates a similar rhythmic ostinato. One year later, Jimmy Page (who produced and performed on 'Beck's Bolero') and John Paul Jones (who also performed on 'Beck's Bolero') would incorporate an identical rhythmic ostinato into 'How Many More Years'. SOURCES

Davis, Stephen. 1995. Hammer of the Gods: Led Zeppelin Unauthorized. Pan Books, an imprint of Macmillan General Books; London, England. Shadwick, Keith. 2005. Led Zeppelin: The Story of a Band and their Music 1968-1980. Backbeat Books; London, England. Tolinski, Brad. 2012. Light & Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page. Crown Publishers; New York, NY. Wall, Mick. 2008. When Giants Walked the Eart: A Biography of Led Zeppelin. St. Martin's Griffin; New York, NY. I've been researching and analyzing Led Zeppelin for the past few months, reading every book I can get my hands on and regularly listening to all of their albums. One book I encountered was Experiencing Led Zeppelin: A Listener's Companion by Gregg Akkerman. What intrigued me was that Gregg has a background as a musician - he earned a Doctor of Arts in Music Theory & Composition from the University of Norther Colorado (coincidentally, the same degree program I'll start this fall at Ball State University). Most Zeppelin authors I've read are music journalists - not necessarily musicians themselves, much less music theorists. And it shows. But Gregg's extensive musical education, knowledge, and experience as a practicing musician yield an entertaining and enlightening read. I managed to find Gregg on Facebook, and we started an email dialog. I asked him if he'd be interested in an interview for my blog, to which he accepted. Our conversation is below. Led Zeppelin is often called "the greatest rock band in history". Why, in your opinion? I don’t think they are the greatest in history because other bands lasted longer and prevailed through several changes in popular music. I do think they were the greatest rock band of their time period for several reasons. Besides the fact that they looked great on stage and fully embraced the concept of “rock stars,” they were simply man-for-man better musicians and songwriters than other bands of the time. Singers like David Coverdale and Glenn Hughes are roughly as good as Plant, but none of them ever came up with melodies and lyrics as strong as “Kashmir,” “In the Light,” “Ten Years Gone,” etc. Page is not only a great guitarist but an absolute brilliant producer. He’s the main reason every Zeppelin album still sounds good today. Jones is the perfect triple threat as a bassist, keyboardist, and arranger. And Bonham has proven to be gold standard for all rock drummers since the first Zeppelin album. Throw in the tough-guy management style of Peter Grant and there’s the recipe for an absolutely great band. How do you respond to those who take the opposite approach and claim Zeppelin is a charlatan - that they're all marketing with no substance? I would recall the facts of the time period the band got up and rolling. They didn’t do much of what we call promotion other than print ads and playing great shows. They almost never appeared on TV either performing or being interviewed. They didn’t sail inflatable pigs over England. They didn’t qualify as a super group because Plant and Bonham had almost no popularity before Zeppelin. They didn’t even release singles to to increase radio airplay in their home country. They are certainly guilty of not crediting the source of several blues numbers from their early days but most the groups of the time did the same thing. It was wrong, but hardly unusual. They just got too famous and wealthy for it to be ignored. Along similar lines, many people have cited "Stairway to Heaven" as the greatest single rock song of all time. Do you agree? “Greatest” is always problematic, but “Stairway” is certainly a great song. It was the culmination of Page’s unique songwriting style striving to combine soft and hard, light and dark. He had touched on those attributes with things like “Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You,” but it all came together on “Stairway.” Again, I say look at other groups of the time and there was simply no one else putting out songs like that: a long form of multiple sections that drives wonderfully towards the conclusion, great musicianship on all parts, interesting lyrics, a stunning guitar solo, inspired singing, and no reliance on an actual chorus. What's your personal background and education? Eight years of piano lessons as a kid, years of banging it out in garage bands, 15 years of actually making a living as a keyboardist in San Diego, 12 years as a college educator (doctorate of Music Theory and Composition from University of Northern Colorado), written a couple books, and now back to performing again. How did you come to Led Zeppelin? As a kid in the 1970s I was always intrigued by the LP records my older brothers had laying around and Zeppelin, along with Pink Floyd, Yes, Rush, and Emerson, Lake and Palmer all stood out. I can still remember when In Through the Outdoor was released and you didn’t know which photo was on the album cover until you bought it and removed the brown paper wrapper. That was a big moment for a Zep fan back then. And how did you end up writing a book about them? I got connected with the acquisitions editor at the Rowman and Littlefield Publishing Group and they were looking for someone to supervise a new series of books called the Listerner’s Companion designed to explain to non-musicians how and why the music of various composers or bands has stood the test of time. So besides recruiting authors and overseeing their writing, I wrote Experiencing Led Zeppelin as a book of my own in the series. It was a dream come true that all those hours listening to Zeppelin as a kid had laid the foundation for me to write about their music as an adult. So much has been said and written about Led Zeppelin already. Is it even possible to say anything new? It certainly seems so. We’re now at the 50th anniversary of their first album and the fascination with the band is still palpable. It’s amazing, considering their complete studio output was only 9 albums. What's your favorite Zeppelin album and song? Why? The first album just never gets old to me. It’s exceptionally rare for a band to have a first album so fully formed. Page had such a clear concept of what he was going for that once he found the right personnel, it just launched. Bands like Van Halen, Kiss, and Aerosmith kicked around a long time trying to get traction, but Zeppelin just exploded from the few months between their first-ever rehearsal to the release of the debut album. In addition, Physical Graffiti is an excellent album because of the variety of material, and I still give Presence the nod for being a no-nonsense rocker. As for single songs, I don’t have an absolute favorite but I’ve probably listened to “Since I’ve Been Loving You” more than any other. It’s got everything in it that I love about the band. You've also written a book titled The Last Balladeer: The Johnny Hartman Story. Tell me about that book. I played a lot of jazz and blues in my 20s and became fascinated with the recording of “Lush Life” from Johnny Hartman and John Coltrane. Then, in my 40s I was a college professor writing a journal article about Coltrane and wanted some quick biographical information on Hartman, only to find that there wasn’t much out there and most of it disagreed on basic facts like his age and birthplace. Writers are always on the lookout for that kind of daylight: an interesting subject that hasn’t already been heavily or accurately covered. I wrote up a sample chapter and got a publisher interested. The Last Balladeer: The Johnny Hartman Story came out in 2012 and was nominated for Jazz Book of the Year by the Jazz Journalists Association which I’m proud of because those folks are hard to impress. Several of the artists I interviewed have passed away since then so I’m grateful for chance to communicate when we did. I understand you now work as a professional pianist on cruise ships. Does your knowledge and understanding of Zeppelin and Hartman inform your playing at all? I work on cruise ships 6 months a year playing about 4 hours a night, 6 nights a week and I play and sing music of every conceivable genre to keep a crowd engaged. I do get the occasional request for “Lush Life” and Zeppelin and I definitely think I’ve got added layers of insight because of my studying the music so deeply. It’s stuff the general audience has no clue about, but I know precisely what phrasing, chords and riffs are played here and there and that provides a private moment of self satisfaction. What's next for you? Any more books (about Zeppelin or otherwise) in the works? There’s always several concepts bouncing around my head. I do have an idea for a Zeppelin-related book but I’m having too much fun getting paid to cruise the Caribbean. Gregg's books are available for purchase on Amazon.com. For more information, you can visit his website and YouTube channel.

Form: deceptive AABA/compound simple (AA'Bx2) 0:00-0:06 Introduction 0:00 (d) Tag B (1) 0:03 (c) Tag A (1) 0:06-0:25 (A) Verse 1 0:06 (a) “As I walk...” (2) 0:11 (a) “And a train...” (2) 0:16 (a') “There is no doubt...” (4*) 0:25-0:44 (A') Verse 2 0:25 (a) “Just a simple guy...” (2) 0:30 (a) “A ray of sunshine...” (2) 0:35 (a'') “There's nothing more...” (4*) 0:44-1:22 (B) Chorus 1 0:44 (b) “All I need...” (2) 0:49 (b) “All you gotta give...” (2) 0:55 (c) Tag A (1) 0:57 (b) “All I need...” (2) 1:04 (b) “All you gotta give...” (2) 1:08 (c) Tag A (1) 1:11 (d) Tag B (1) 1:13 (c) Tag A (1) 1:16 (d) Tag B (1) 1:19 (c) Tag A (1) 1:22-1:41 (A) Verse 3 1:22 (a) “I'm so glad...” (2) 1:27 (a) “Got me a fine woman...” (2) 1:32 (a') “One thing...” (4*) 1:41-2:00 (A') Verse 4 1:41 (a) “Standing...” (2) 1:46 (a) “People go...” (2) 1:51 (a'') “Total disgrace...” (4*) 2:00-2:37 (B) Chorus 2 2:00 (b) “All I need...” (2) 2:05 (b) “All you gotta give...” (2) 2:10 (c) Tag A (1) 2:13 (b) “All I need...” (2) 2:18 (b) “All you gotta give...” (2) 2:23 (c) Tag A (1) 2:26 (d) Tag B (1) 2:29 (c) Tag A (1) 2:32 (d) Tag B (1) 2:34 (c) Tag A (1) 2:37-4:06 (C) Coda (e) [2-bar riff] x17 (repeat & fade) I'm gonna try something new here, with a PDF transcription to accompany this structural analysis:

There's an objective analysis; now for my subjective opinions and critique.

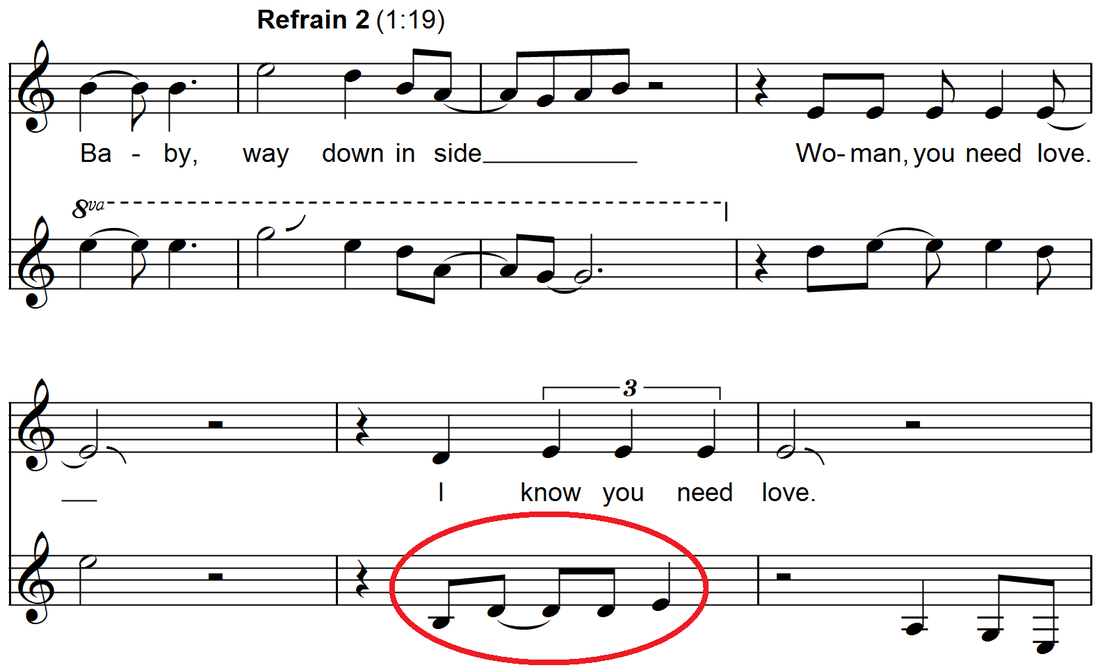

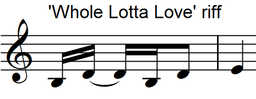

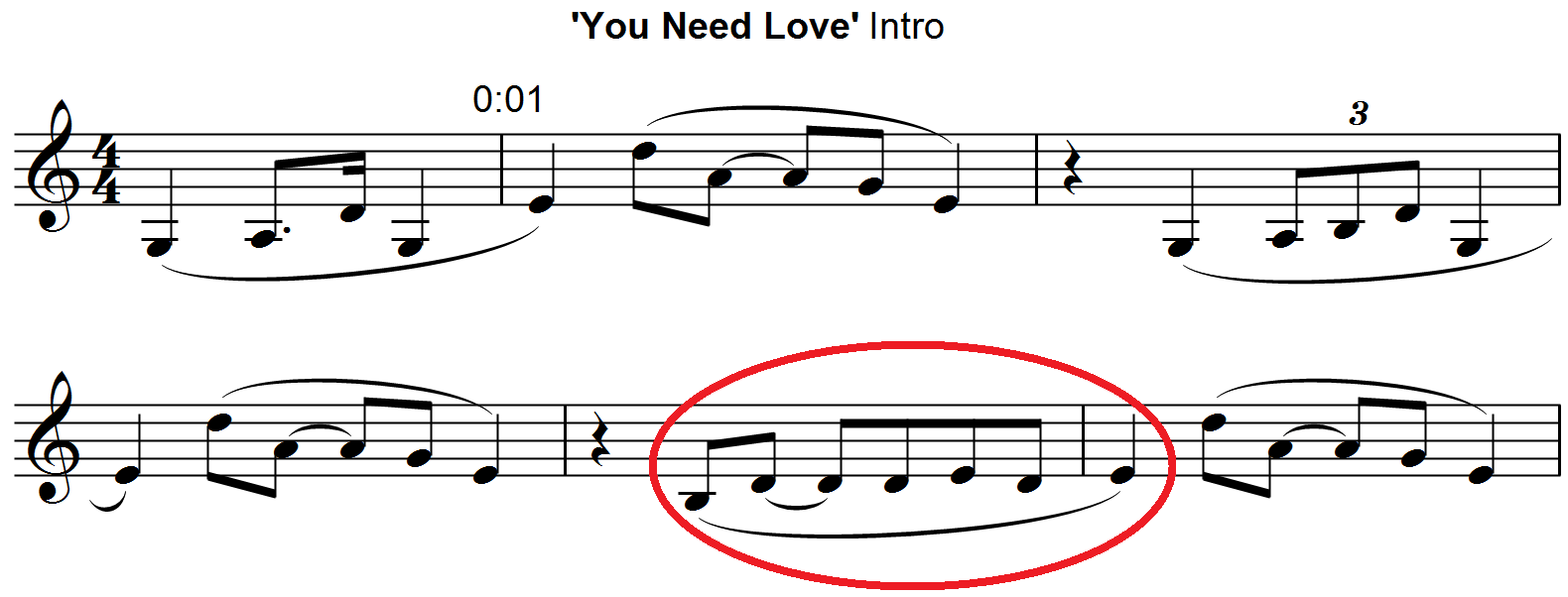

While I really like this song – it's a total rocker – they could easily have done a lot more with it. I usually prefer economy, but in this case the song could have been twice as long and twice as good. Led Zeppelin is wonderful at spinning out large-scale formal designs (with a duration of 7:24, the previous track on Led Zeppelin III, 'Since I've Been Loving You', is a good example), but with 'Tiles' they take take the easy way out. The raw material is strong, and it begs for a large-scale treatment. I could easily see it employing a series of tempo changes and modulations. The unison guitar/bass riffs in the verses cry out for exploratory development. And they could've used the (e) riff from the coda as a transition to a bridge in the middle, or they could use the tricky rhythms at the end of each verse to execute a metric modulation to 12/16 or 9/16 bridge (rather similar to what The Beatles did in 'I Me Mine'). There's so much that could be done with this song, but they didn't do much of anything with it. 'Tiles' has the potential to be an epic, like 'Loving You' or 'Stairway' or 'Kashmir', but that potential is never realized. And I'm just not sure why not... They could have omitted one of the weaker songs from the album, like 'Friends' or 'Celebration Day' or 'That's the Way', to make room. Not only would that have made the song stronger, it would have made the album stronger, too. Zep dropped the ball with this song. It's really good as is, but it could've been spectacular. Willie Dixon, probably the foremost blues composer of the mid-20th Century, penned a song titled 'You Need Love', which he gave to Muddy Waters to record in 1962. Seven years later, that song's lyrics would be the inspiration for Led Zeppelin's 'Whole Lotta Love'. Muddy Waters: 'You Need Love' (1962), Third Verse (1:57-end) I ain't foolin', you need schoolin' Baby, you know you need coolin' Woman, way down inside Woman, you need love You got to have some love Mmmm She got to have some love Mmmm She got to have some love Led Zeppelin: 'Whole Lotta Love' (1969), First Verse (0:11-0:45) You need coolin', baby, I'm not foolin' I'm gonna send you back to schoolin' Way down inside, honey you need it I'm gonna give you my love I'm gonna give you my love Oh! Wanna whole lotta love Wanna whole lotta love Wanna whole lotta love Wanna whole lotta love Dixon sued Zeppelin for plagiarism in the 1980s, settling out of court for an undisclosed amount. While the lyrical similarities are undeniable, there remains some confusion whether or not the music (independent of the words) is original or not. Jimmy Page claimed the former: "If you took the lyric out and listened to the track instrumentally, it is clearly something new and different - a completely original piece of music" (English, page 198). But Zeppelin biographer Mick Wall claimed the latter: "Even the most memorable part of the song, that punchy B-D-B-D-E riff, was derived from the original guitar refrain of the Muddy Waters original" (Wall, page 149). Unfortunately, Wall provides no evidence to support his claim. Nor does he appear to understand what a refrain is. (It's a lyrical device - not a musical one - so I'm not sure how a "guitar refrain" is even possible since a guitar can't sing lyrics.) While Waters does use a refrain (corresponding to the title lyrics) three times in the song (0:19-0:40, 1:19-1:31, and 2:07-2:16 - each one slightly different in content and duration), the accompanying guitar (which more or less double the vocals) is not strongly related to the Zeppelin riff. The best example (the closest to 'Whole Lotta Love') is heard in the second of those three refrains. The circled measure does share modest similarities to 'Whole Lotta Love' in both pitch (B-D-E) and its syncopated rhythm... ... but it's only a superficial resemblance. If this is what Wall has in mind, it's a pretty weak case. It's only heard twice (once in the first refrain, once in the second), and it's not very prominent (you have to really look for it to find it). Another clue comes from author Tim English, in his book Sounds Like Teen Spirit: "The guitar lick on 'Whole Lotta Love['] is not dissimilar from what is played on Waters' 'You Need Love'" (English, page 197). English makes no mention of the refrain, so I assume he's referring to the opening guitar licks. I've transcribed the first several measures below. Yes, the fourth full measure also bears a passing resemblance to 'Whole Lotta Love' in pitch and rhythms, but I find that, too, to be more incidental than significant. I have to agree with Page (and against Walls and English) on this one: 'Whole Lotta Love' is musically independent from 'You Need Love'. There are superficial musical similarities and a strong similarity in character (they're both blues songs), but nowhere near the resemblance of the lyrics. Lastly, Robert Plant's vocals are worth mentioning. Just as he borrowed the lyrics from Muddy Waters, so too he borrows the vocal style of Steve Marriott, lead singer of The Small Faces, who released their own version of the song, 'You Need Loving', in 1966. Plant greatly admired Marriott's vocal style, calling him a "master of contemporary white blues" (Shadwick, page 262), and deliberately imitated it. And nowhere is that influence more apparent than on 'Whole Lotta Love'.

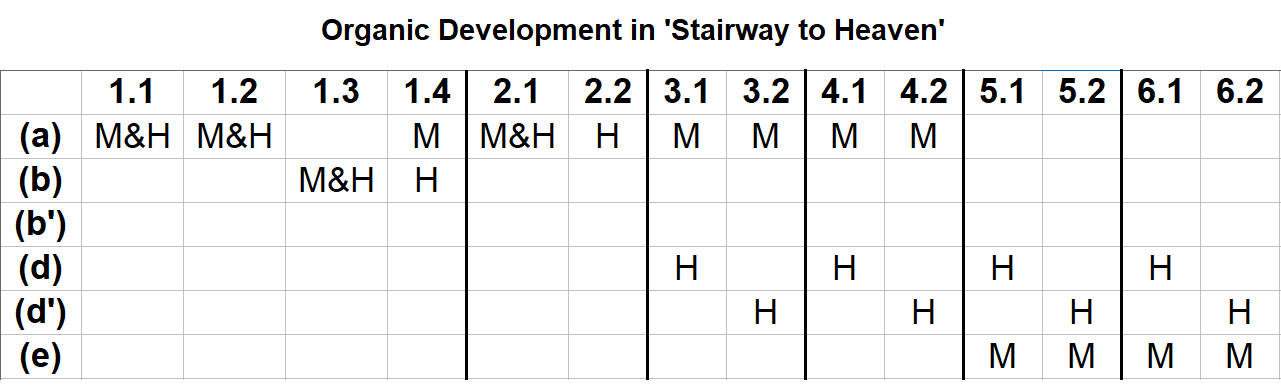

SOURCES English, Tim. 2016. Sounds Like Teen Spirit: Stolen Melodies, Ripped-Off Riffs, and the Secret History of Rock and Roll. [No publisher or city given]. Shadwick, Keith. 2005. Led Zeppelin 1968-1980. Backbeat Books; San Francisco, CA. Wall, Mick. 2008. When Giants Walked the Earth: A Biography of Led Zeppelin. St. Martin's Griffin; New York, NY. Having looked at each section of 'Stairway to Heaven' in detail, now we can draw conclusions and address why it's one of the greatest achievements in rock history. My answer to why it's so great is its organic development – the way the melody and harmony of the verses grow out of what came before, continuously blending old material with new material. This graph illustrates: The x axis indicates the verse # and phrase #, separated by a period (ex: 1.4 means verse 1, phrase 4; 3.1 means verse 3, phrase 1). The y axis refers to the phrases. M = melody H = harmony So the melody and harmony are together for the first three phrases of the first verse, and the first phrase of the second verse, but they are split for the fourth phrase of the first verse, and all of the third through sixth verses. It is that split that allows for organic development. Because when the harmony uses the new (d) phrase in verse 3, the melody simultaneously keeps the (a) phrase. Then in verse 5, the melody uses the new (e) phrase, while the harmony simultaneously keeps the (d) harmonies. Each step grows out of what came before by incorporating something new while also retaining something old. The fundamental goal for any composer is to keep the material familiar and internally consistent enough so that it clearly belongs together, but different enough to avoid monotony. A succession of unrelated material will appear disjointed and confusing, while a succession of unchanging material will become predictable and boring. Compositional skill is in large part the ability to balance the two. And one of the best ways to strike that balance is through structure. Indeed, the organic growth and structure of 'Stairway to Heaven' strikes that balance as well as any piece of music I've ever encountered.

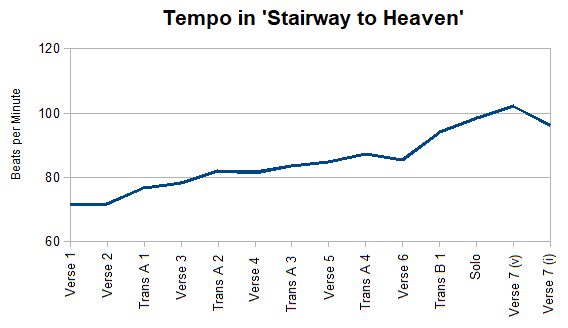

One aspect I've ignored so far is tempo. The song gradually builds speed, before winding down again at the end. 0:00-0:54 Introduction: 64 beats in 53.8 seconds = 71.4 beats per minute 0:54-1:48 Verse 1: 64 beats in 53.7 seconds = 71.5 bpm 1:48-2:15 Verse 2: 32 beats in 26.8 seconds = 71.6 bpm 2:15-2:40 Transition A 1: 32 beats in 25.0 seconds = 76.8 bpm 2:40-3:07 Verse 3: 36 beats in 27.6 seconds = 78.3 bpm 3:07-3:31 Transition A 2: 32 beats in 23.4 seconds = 82.1 bpm 3:31-3:57 Verse 4: 36 beats in 26.5 seconds = 81.5 bpm 3:57-4:20 Transition A 3: 32 beats in 23.0 seconds = 83.5 bpm 4:20-4:45 Verse 5: 36 beats in 25.5 seconds = 84.7 bpm 4:45-5:08 Transition A 4: 32 beats in 22.0 seconds = 87.3 bpm 5:08-5:35 Verse 6: 36 beats in 25.3 seconds = 85.4 bpm NOTE: The measure that connects Verse 6 and Transition B 1 uses a fermata to artificially extend its temporal duration, which skews the numbers. To be consistent, I'm omitting that measure from this analysis. 5:35-5:56 Transition B 1: 31.5 beats in 20.1 seconds = 94.0 bpm 5:56-6:45 Solo: 80 beats in 48.8 seconds = 98.4 bpm 6:45-7:47 Verse 7 6:45-7:27 [vocal]: 18 measures = 72 beats in 42.3 seconds = 102.1 bpm 7:27-7:47 [instrumental]: 28 beats in 17.5 seconds = 96.0 bpm NOTE: I'm again omitting the final measure as it uses another fermata, which skews the numbers. 7:47-8:02 Coda: freely (not in rhythm) Here's the same information in the form of a line graph: With two minor exceptions that fall within the margin of error, the tempo consistently increases throughout the song until the end. And this was done very much on purpose. "When I did studio work," acknowledged Jimmy Page, "the rule was always: you don't speed up. That was the cardinal sin, to speed up. And I thought, right, we'll do something that speeds up" (Wall, page 242).

Interestingly, the climax of the song as a whole comes at 5:56 (at the onset of the solo), but the tempo's climax is at 6:45 (at the onset of verse 7), where it peaks at 102 beats per minute. SOURCES Wall, Mick. 2008. When Giants Walked the Earth: A Biography of Led Zeppelin. St. Martin's Griffin, New York, NY. While the first five and a half minutes illustrate sophisticated organic growth, the solo is entirely comprised of repetitions of a new two-bar phrase (g). The rhythmically unstable Transition B followed by new material emphasizes the arrival of the solo as the climax of the song. 5:56-6:45 (D) Solo (20 measures) (g) |a G |F | x10 The seventh and final verse adopts the same (g) two-bar phrasing of the solo, repeating it 13 more times (for a total of 26 measures) with Plant adding vocals to the first nine phrases. 6:45-7:47 (D') Verse 7 (26 measures) 6:45 (g) |a G |F | “As we wind...” 6:50 (g) |a G |F | “Our shadows...” 6:54 (g) |a G |F | “There walks...” 6:59 (g) |a G |F | “Who shines...” 7:04 (g) |a G |F | “How everything...” 7:08 (g) |a G |F | “And if you listen...” 7:13 (g) |a G |F | “The tune will come...” 7:18 (g) |a G |F | “When all are...” 7:22 (g) |a G |F | “To be a rock...” 7:27 (g) |a G |F | [instrumental] 7:32 (g) |a G |F | [instrumental] 7:37 (g) |a G |F | [instrumental] 7:42 (g) |a G |F | [instrumental] The final four phrases are instrumental and ritard the tempo, leading to... The coda wraps things up be reprising the title lyrics and melody used several times earlier in the song. This final iteration, however, omits any underlying chord changes, leaving Plant's vocals fully exposed.

7:47-8:02 Coda “And she's buying...” Continuing the organic development we saw in verse 3, verse 5 retains the (d) harmonies while simultaneously introducing the new (e) melody. 4:20-4:45 (C) Verse 5 (9 measures) 4:20 (d & e) |C G |a |C G |a | “If there's a bustle...” 4:31 (d' & e) |C G |a |C G |a |C G | “There are two paths...” Verse 6 is identical to verse 5, just with different lyrics.

5:08-5:35 (C) Verse 6 (9 measures) 5:08 (d & e) |C G |a |C G |a | “Your head...” 5:19 (d' & e) |C G |a |C G |a |C G | “Dear lady...” Verse 3, like verse 2, contains two phrases. Those phrases are identical except that the latter is extended by a single measure (five bars long instead of four). Both reprise the (a) melody from the first and second verses, but with new (d) harmonies. 2:40-3:31 (B) Verse 3 (9 measures) 2:40 (a & d) |C G |a |C G |a | “There's a feeling...” 2:52 (a & d') |C G |a |C G |a |C G | “In my thoughts...” This third verse cannot be called a new section because it brings back an old melody. But it also cannot be called an old section, either, because the chords are new. So it's half new, half old. This is a technique known as organic development because the music grows out of what came before, just like a seed sprouts and flowers. I analyzed the organic development of 'Good Times Bad Times' earlier. This is the same technique, but on a much grander scale. While Verse 3 is the first time those (d) harmonies are used, they will be heard again six more times (two each in verses 4, 5, and 6): 3:31 (d) Verse 4 3:42 (d') Verse 4 4:20 (d) Verse 5 4:31 (d') Verse 5 5:08 (d) Verse 6 5:19 (d') Verse 6 Verse 4 is identical to verse 3, just with different lyrics.

3:31-3:55 (B) Verse 4 (9 measures) 3:31 (a & d) |C G |a |C G |a | “And it's whispered...” 3:42 (a & d') |C G |a |C G |a |C G | “And a new day...” |

Aaron Krerowicz, pop music scholarAn informal but highly analytic study of popular music. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed