|

In the third semester of undergraduate music theory (which I'll be teaching this fall), we cover modal mixture, the Neapolitan chord, and augmented sixth chords, among other topics. I've kept an eye out for any pop music that employs all three so I can use it on an exam, and I've finally found the perfect example: Zelda's theme by Koji Kondo.

2 Comments

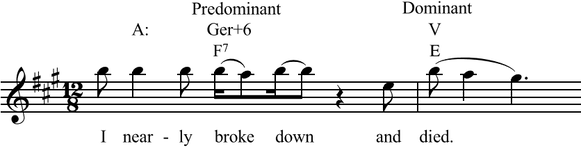

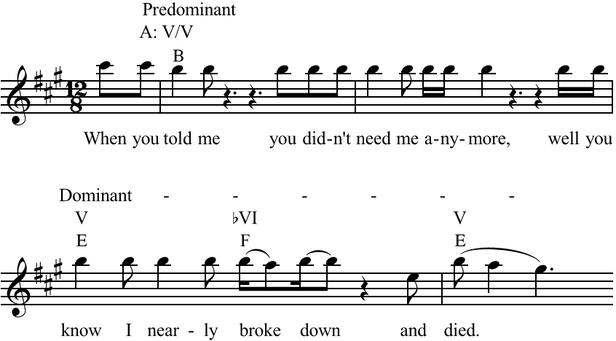

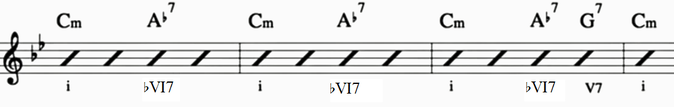

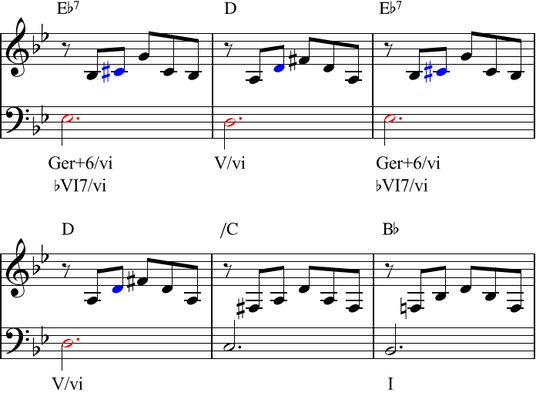

I'll be teaching Theory 3 this fall. In preparation, I've been reviewing the concepts we'll cover, and finding as many pop examples as I can to supplement the textbook's classical examples - including mode mixture, the Neapolitan chord, modulations to distantly-related keys. The next chapter is on augmented sixth chords. Though quite prevalent in the classical repertoire, there seems to be much debate over whether or not augmented sixths are used in popular music. This enthusiastic blogger insists there's one in The Beatles' 'Oh! Darling', arguing that the F7 (bVI in A major) at the end of the bridge functions as an enharmonic German augmented sixth, resolving as any good predominant should to V (in this case E). But there are two glaring problems with his interpretation. First, it's an F chord - not an F7 - which means it cannot be an augmented sixth, even accounting for enharmonics. Second, that F chord is not a predominant. Yes, it progresses to V, but it also progresses from V. So a more careful consideration of the context shows it to be a chromatic upper neighbor, and thus its function is that of a dominant prolongation instead of a predominant. (The predominant is the V/V, B major, heard in the two bars immediately preceding.) So 'Oh! Darling' clearly does not employ an augmented sixth - for multiple reasons. But what about songs where the bVI does have a seventh, and where it truly is a predominant? The following YouTube video gives four such examples. In the first example, Tom Waits' 'Dead and Lovely', he analyzes Ab7 as a Ger+6 in C minor. This is a much better example than 'Oh! Darling', but I maintain that it is not an augmented sixth. The defining characteristic of +6 chords is the voice leading of the augmented sixth resolving outwards to an octave. In this case, however, the seventh of that Ab7 (the note Gb or F#) does not resolve up to G, but rather it planes down to F (the seventh of the G7). Without the proper voice leading, I cannot justify calling the chord an augmented sixth. To do so is to over-complicate an otherwise standard progression. Here's how I would analyze the same passage, without the augmented sixth: I have the same problem (the voice leading discourages an interpretation with an augmented sixth) with the second example, 'Love in My Veins' by Los Lonely Boys. The third and fourth examples, however, do feature proper augmented sixth voice leading, and so in these two instances the +6 is (more) justified. In my transcription of The Beatles' 'I Want You (She's So Heavy)' below, the G#s resolve up to A (shown in blue), while the Bbs resolve down to A (shown in red). This is exactly how augmented sixths should resolve, thus the Ger+6 label is appropriate. The same voice leading (and color coding) is found in 'Blackout' by Muse. So in 'I Want You (She's So Heavy)' and 'Blackout', the Ger+6 interpretation is acceptable, but what advantage is there over simply calling them bVI7? In classical harmony, the augmented sixth chords (especially the Italian and French +6s) cannot be explained any other way - indeed, that's why +6s were invented: to help make sense of something that could not make sense otherwise. But in pop harmony, even the most convincing +6 chords could easily be simplified to bVI7. With nothing to gain through employing +6s in pop harmony analysis, I see no reason to use them.

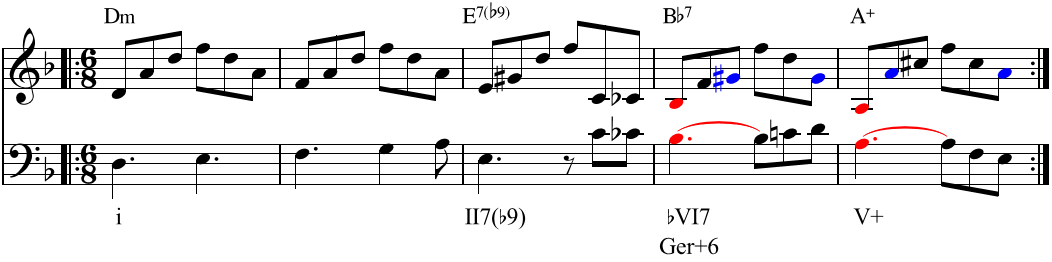

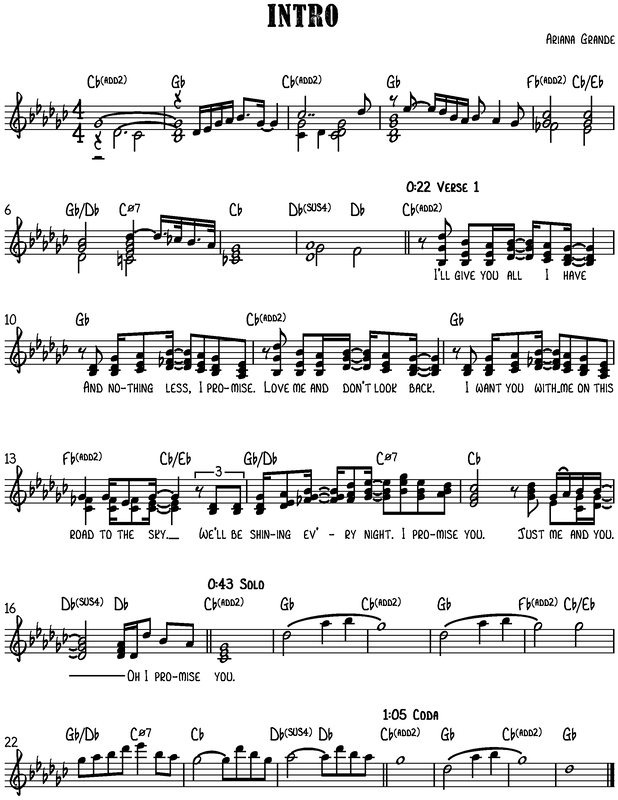

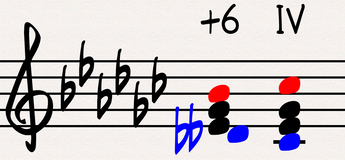

Yesterday, while walking my puppy dog, I did what I always do: put in ear phones. I started with the audio book A Generation of Sociopaths: How the Baby Boomers Betrayed America by Bruce Cannon Gibney, but when that proved too depressing, I switched to music. A few days ago my wife commented on how she liked Ariana Grande's voice, so when I saw Grande's 2014 album My Everything in my library, I gave it a go. The first track, appropriately titled 'Intro', immediately captured my attention. First, a full structural analysis: 0:00-0:22 (A) Instrumental Introductory Verse (8) (a) statement (2) Cb | Gb (a) restatement (2) Cb | Gb (b) departure (2) Fb2 Cb/Eb | Gb/Db CØ7 (c) conclusion (2) Cb | Db4-3 0:22-0:43 (A) Verse 1 (8) (a) statement (2) Cb | Gb "I'll give..." (a) restatement (2) Cb | Gb "Love me..." (b) departure (2) Fb2 Cb/Eb | Gb/Db CØ7 "road to the sky..." (c) conclusion (2) Cb | Db4-3 "I promise you..." 0:43-1:05 (A) Instrumental Solo (8) (a) statement (2) Cb | Gb (a) restatement (2) Cb | Gb (b) departure (2) Fb2 Cb/Eb | Gb/Db CØ7 (c) conclusion (2) Cb | Db4-3 1:05-1:19 (A') Instrumental Coda (4) (a) statement (2) Cb | Gb (a) restatement (2) Cb | Gb Each section is fundamentally the same, despite surface-level differences, rendering the structure a Simple (or Strophic) design. The coda, though related, is clearly supplemental to the form because its abbreviated. You could argue that the intro is also supplemental (introductions are by definition supplemental), yielding an A x2 with intro and coda; however, since the intro is a full iteration of the module, I would count it as the first A section, making it an A x3 with coda. Either interpretation works, but I find the latter more accurate. That being said, it's not quite as straightforward as it might appear because Grande plays with the phrase rhythms during the solo. While the underlying harmonies retain the same two-measure hypermetric phrasing as the rest of the song, the melodic instrumental phrasing of the solo (starting in bar 17) through the coda is offset by one measure. This creates a greater sense of finality at the song's end by giving the impression of concluding on a hypermetrically strong beat, even though it's actually a weak beat. This is brilliant songwriting! Even more fascinating are the chords. Each departure phrase halves the harmonic rhythm, fitting two chords per bar (one chord every two beats, for a total of four chords in two measures), where the other phrases employ just one chord per bar (one chord every four beats, for a total of two chords in two measures). The fourth of those four departure phrase chords is the most unusual and interesting: It's a C half-diminished seventh (C-Eb-Gb-Bb). Half-diminished sevenths are rare in popular music. The Beatles used them in only two of their 211-song official catalog: 'Because' and 'You Never Give Me Your Money' (curiously, one Lennon song and one McCartney song, both from 1969's Abbey Road). No doubt there are other pop songs that employ this rare and intriguing harmony, but I can't think of any off the top of my head. Anyway, Ariana uses the half-diminished seventh somewhat differently than did John and Paul. (I don't know enough about Grande to know if she's a composer as well as a singer, but for the sake of this blog I will assume she is.) All three songwriters use the chord as a pre-dominant, but where The Beatles always employ it as a ii chord, Grande's use of the same harmony is not so evident. This ambiguity stems from the fact that it's almost several other chords, but not quite. Interpretation One: vi/#4 At its simplest, it could be interpreted as a conventional vi chord, but with a #4 (or b5) in the bass. This would render the progression (technically a retrogression) as bVII-IV-I-vi (in Gb: Fb-Cb-Gb-eb), which appears totally reasonable to the eye, though I can't think of any other song to use that particular pattern in a single phrase. (The Beatles used it in 'Dig A Pony', but as incongruent constituents bridging two consecutive phrases.) The problem is I just don't hear it that way. In other words, yes, this interpretation looks good, but I don't think it accurately captures what I'm hearing. Interpretation Two: augmented sixth What I'm hearing, that the above interpretation neglects, is how the C and Bb function like an augmented sixth chord. Enharmonically reinterpreting the C as Dbb gives it properly spelled augmented sixth function, as it resolves by half step down to Cb (shown in blue in the example below), just as the Bb resolves up to the same pitch class (shown in red). Okay, so now it does reflect what I'm hearing. But this "fix" creates a few new complications:

Interpretation Three: CTØ7 Common tone diminished chords are standard - they're a staple of romantic and barbershop styles. So could this mystery chord in 'Intro' be one? I have two problems with that notion. First of all, common tone diminished chords are usually common tone fully diminished seventh chords, where this would be a common tone half-diminished seventh - something I've never encountered before in any style or context. And second, common tone diminished chords are "supposed" to keep the root as the common tone, where in this case the third and the fifth are common tones while the root is not. So, technically, yes, this is a common tone diminished - it's just not what music theorists normally mean when they use that term. The bottom line is: I have no idea how to interpret this chord. And that ambiguity makes for absolutely fascinating and engaging analysis and consideration.

In the face of all this ambiguity, it's difficult - maybe even impossible - to make any clear verdicts. Yet I can draw one conclusion with utmost certainty: I'll be listening to a lot more Ariana Grande! |

Aaron Krerowicz, pop music scholarAn informal but highly analytic study of popular music. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed