|

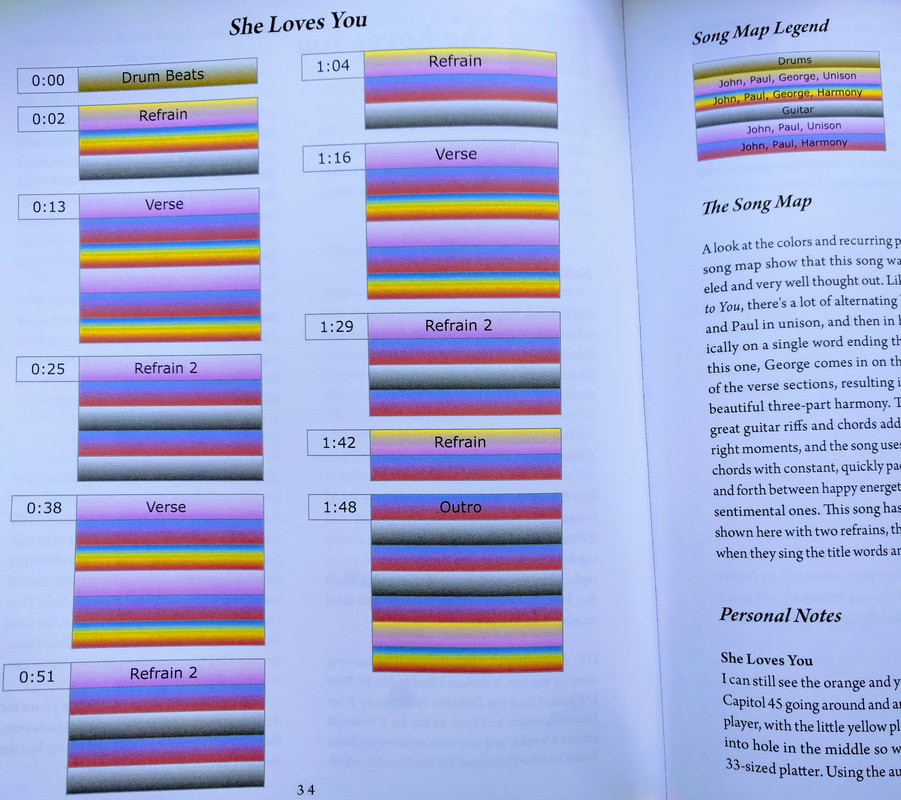

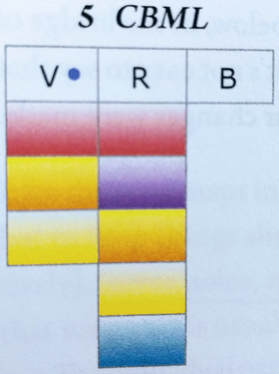

The other day I received an email from a man named Brian Hebert. He recently published a book titled Blue Notes and Sad Chords: Color Coded Harmony in The Beatles 27 Number 1 Hits, and offered to mail me a complementary copy. I eagerly accepted Brian's offer, but countered by saying he could save shipping costs by just giving it to me in person. Since he lives in Massachusetts, and I'm speaking throughout the Bay State this month, why don't we meet in person to chat and exchange books? So we set up a meeting on Wednesday, July 18 at Stone's Public House in Ashland, MA. A splendid time was guaranteed for all! Indeed, the conversation was so engaging that an hour and half passed in what felt like ten minutes! Brian told me all about his experiences writing the book, and how he made various decisions. I happily chimed in with my own stories - good and bad - of whole process. We also conversed about several of the notoriously difficult chords to identify: the intro of 'A Hard Day's Night', the B chord (is it major? minor? is there a seventh?) in 'I Want To Hold Your Hand'. At one point during the meal, I asked Brian if he'd be interested in a blog interview to help promote the book. He heartily agreed, and I hope to publish that shortly. After generously picking up the check, Brian left the restaurant with my BEATLESTUDY, volume 1: Harmonic Analysis of Beatles Music in hand; I departed with Blue Notes. And I've been carefully reading it for the last several days. Below is my summary and review. The book is divided into three parts. The first section is introductory, establishing the basic premises for the book. “Hundreds of books in all sizes and shapes have been written about the Beatles,” Hebert writes. “Many are biographical … some books are primarily collections of photographs. Still other books help readers peer behind the curtains … A small number of books actually describe the music in detail [my emphasis]" [page 4]. An author after my own heart! He continues: “Typically written by musical experts, most of these books require the reader to possess a detailed understanding of music theory and a very specialized vocabulary, and as such are generally inaccessible to the average fan. … One goal of this book is to bridge that gap, and provide lovers of Beatles music with a unique and enjoyable way to understand some of the key musical elements that made the four lads from Liverpool so successful, without needing to be a musician or possess any specialized knowledge of music theory. … One of the key ideas this book hopefully gets across is that these musical concepts can be conveyed and understood intuitively, using relatively simple, color-rich graphics, which do not at all require an in-depth understanding of music theory” (pages 4, 6). Hebert makes it clear this is not an academic textbook, though it is analytic in nature: “This book is not intended as a scholarly work. You won't find footnotes or a list of references, and Wikipedia has been used as a main source for many facts” (page 12). The second section features color-coded “song map” textural analyses of The Beatles' 27 #1 hits (as included on the album 1), or in his own words, “the song maps show which Beatles are singing on the different parts of a song, and whether they are singing alone or together, in unison or in harmony” (page 3). In other words, the colors represent who is singing what. “If we assign a primary color to each singing Beatle voice (John red, Paul blue, and George yellow) and color code the parts of a song, we can see where they were singing alone, using a primary color, or together in unison or harmony, using secondary colors” (page 8). 'She Loves You' is a particularly vibrant example: Because the combinations of voices in this song are so varied (see the song map legend at the top right of the graphic), the song map's coloration is equally varied. The third and final section, for which the book is titled, analyzes harmony through a new color scheme, “using the analogy of an artist's palette of paints” (page 3). In this case, color represents not texture but harmony: red for I, green for ii, light gray for bIII, purple for iii, orange for IV, yellow for V, dark gray for bVI, light blue for vi, dark blue for bVII, and beige for vii. In general, brighter colors correspond to happier-sounding chords, where darker colors correspond to sadder-sounding chords. Here, for example, is the palette for 'Can't Buy Me Love': What this palette shows is that the verses employ the bright-sounding I (red), IV (orange), and V (yellow), while the refrains supplement with the dark-sounding iii (purple), and vi (blue). I've always found 'Can't Buy' fascinating for precisely this reason: The verses sound much happier than the refrains (what I would call choruses, but that's semantics and I won't get into it here). Furthermore, the lyrics reinforce this shift. In the darker-sounding refrains, the lyrics are negative, with Paul describing what cannot be done (“Can't buy me love...”). But in the brighter-sounding verses, the lyrics are more positive, describing what can be done (“I'll buy you a diamond ring...”, “I'll give you all I've got...”). Also, observant readers might notice a little blue dot in the above graphic, just to the right of the “V”. This indicates the use of a “blue note”, in which the pitch of a tone is lowered (ie, in a C major chord, the note E would be “normal”, while the note E-flat would be a “blue” note) for expressive reasons. “They can give a low-down, swampy, or lonesome feeling,” writes Hebert [page 17]. In the verses of 'Can't Buy', for instance, Paul frequently sings blue notes: “I'll buy you a dia-mond ring..”, “I'll get you a-ny-thing...”, “I'll give you all I got...”, “I may not have a lot...”, “Say you don't need no diamond rings...”, “Tell me that you want the kind of things...”. The Beatles (and a great many other pop musicians) use blue notes frequently. Where my own work (especially in the last year or two) has turned more analytic and technical, Hebert's Blue Notes and Sad Chords provides an accessible path for the obsessive but non-musician fan who wants to better understand the intricacies and sophistication of The Beatles' extraordinary music. And in addition to the colorful analytics, Hebert balances things out by including lots of non-technical nostalgic info, like calling out other artist’s songs in the charts before and after a Beatles hit, a back story for each number, personal memories and thoughts about the Beatles and the 1960s, and a condensed Beatles timeline. While I'm not a first-generation fan, I imagine the book could be a very pleasurable trip down memory (Penny?) lane for anybody that lived through the Sixties. As the book's back cover states: “Whether you're a long-time baby boomer Beatle fan, a younger newcomer, or somewhere in between, this book will give you an entirely new appreciation for the most amazing band ever.”

Blue Notes and Sad Chords is available for purchase on Amazon.com.

1 Comment

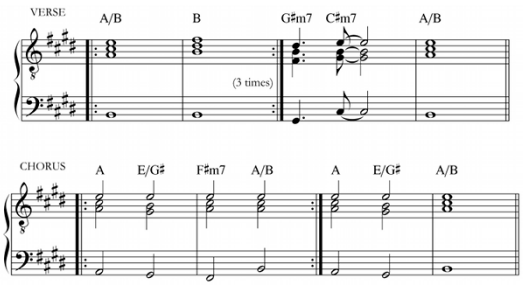

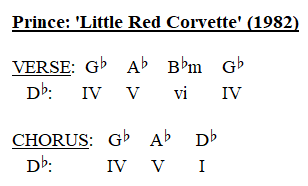

The other day I blogged about my intent to "post summaries and reviews of articles and books by authors who have written about those 'purely musical achievements'." This will be the first such post. Mark Spicer is professor of music at Hunter College in New York, NY. He published an article in Music Theory Online last year in which he cites three examples of how pop musicians “toyed with tonality” by citing “three tonal scenarios”. This blog will summarize Spicer's main points and examples. I will close by relating his ideas to the catalog I know best: The Beatles. The first scenario Spicer considers are fragile tonics, which he defines as “the tonic chord is present but its hierarchical status is weakened”. Among other examples, Spicer cites Hall and Oates' 'She's Gone' (1973). The song is in E major, however the tonic chord is conspicuously absent from the verses, and appears only fleetingly (as a first-inversion passing chord on a week beat) in the choruses. This weakened tonic often corresponds to the lyrics, as is the case in Hall and Oates' 'She's Gone' (1973), in which the fragile tonic reflects the singer's fragile emotional state following a break-up: My face ain't looking any younger Now I can see love's taken her toll on me. She's gone. I 'd better learn how to face it. She's gone. I'd pay the devil to replace her. She's gone. What went wrong? The second tonal scenario are emergent tonics, in which “the tonic chord is initially absent yet deliberately saved for a triumphant arrival later”. Spicer cites Prince's 'Little Red Corvette' (1982) as an example. The tonic D-flat major chord, absent from the verses, emerges in the choruses, "where it serves as a metaphor for the release of the sexual tension built up in the preceding verse." Third are absent tonics, in which "the promised tonic chord never actually materializes.” Obviously this third category is the most difficult to discern for the reason that tonic is never heard - the song's harmony must convincingly imply tonic without actually giving it. From a compositional standpoint, this is tough to do (or at least it's difficult to do well); and from an analytic standpoint, it's heavily dependent on interpretation (how convincingly is tonic implied?). Spicer provides the example of 'Jane Says' (1988) by Jane's Addiction. The entire song consists of just two vacillating G and A chords, yet the song is clearly in D (judging from the sung melody). The tonic D major chord, then, is entirely absent - never heard, not even once, throughout the nearly-five-minute song. So there are Spicer's three categories of fragile, emergent, and absent tonics. How do The Beatles fit into these categories?

Well, the short answer is: They don't! The Beatles tend to be very clear about their tonics, and it's extremely rare to find a section of any given song (much less an entire song) with a fragile, emergent, or absent tonic. John Lennon's 'Glass Onion' (1968) is the sole exception. Lennon said about it: “I was just having a laugh, because there had been so much gobbledegook written about Sgt. Pepper. People were saying, 'Play it backwards while standing on your head, and you'll get a secret message.' … I threw the line in – 'The Walrus was Paul' – just to confuse everybody a bit more" (Dowlding, page 225; Sheff, page 208). So the lyrics aren't supposed to make sense! And indeed, the harmony (appropriately) doesn't make sense, either. In BEATLESTUDY, I analyzed it three different ways: in C major, in A minor, and in F major. None of those three fit perfectly, but between the three I think I covered it pretty well. The only cadences in 'Glass Onion' are the g-C-F progressions (ii-V-I in F major) heard from 0:15-0:19, 0:44-0:49, and 1:34-1:38; and the F-G-a progressions (bVI-bVII-i in A minor) heard from 0:27-0:31, 0:57-1:01, and 1:16-1:20. But if I had to pick "the best tonal interpretation", I'd probably chose C major, even though there are no cadences to confirm that tonality. In fact, every time a potential cadence builds (every time we hear a strong predominant followed by a strong dominant), that expectation is thwarted by meandering harmony. So I think the best interpretation of 'Glass Onion' is with the absent tonic of C major. REFERENCES

I've been on a Led Zeppelin kick lately, listening over and over to their albums and reading everything I can about the band. In one book, I read the following in the preface: “In the wake of the on-the-road-tales-of-debauchery-style Led Zeppelin books that were reaching the market, I felt the balance needed redressing. I saw it as a golden opportunity to celebrate the purely musical achievements [my emphasis] of the group.” I'm normally a stickler for the citation of sources – the lack thereof is one of my biggest annoyances. In this case, however, I'm going to keep the author anonymous because I want to challenge the content, not the writer. This preface - especially the words “purely musical achievements” - resonate strongly with me. In fact in my initial Led Zeppelin blog, I wrote almost identical words: “Much like The Beatles literature, the problem with the extant Zeppelin literature is that so little of it focuses on the music. Many books seem more concerned about lurid descriptions of orgies, or Jimmy Page's obsession with the occult and Aleister Crowley, or 'hidden meanings' in their lyrics and album artwork than they are about the actual music. [Yet] it is, after all, the music – not their salacious love lives or hotel-trashing – that makes Led Zeppelin compelling and worthy of study and criticism a half century later.” And so I was ecstatic to find another author who valued the music most. Unfortunately, I disappointed. Because this author proceeded to write 216 additional pages without once ever addressing the music. In fact, on the subsequent page of the preface, he contradicts his earlier claim: “So if you want to know what Led Zeppelin recorded, and where and when they did so, the details of their session appearances and pre-Zep work, their concert itineraries, a guide to rare Zep collectibles, the instruments they used, extensive discographies and chronologies, a summary of their solo careers and that aforementioned ten album track by track analysis, well it's all here.” He first says he wants "to celebrate the purely musical achievements of the group", but then lists all the different types of information he includes in the book, none of which are the actual music. And it's pretty clear what's happening here: It's not that the author is lying or deliberately deceiving his readers, it's that in this case he is using a generally-accepted but literally inaccurate definition of what constitutes music.

Strictly speaking, music has two fundamental parameters: pitch and rhythm. So if something has no pitch and no rhythm, then it literally cannot be music. Therefore, if an analysis or commentary about music fails to address pitch and/or rhythm (as is the case throughout the book quoted above) then its subject literally cannot be music. This is why toenails can never be music – they have no aurally discernible pitch or rhythm – but the sound of clipping toenails is (or at least could be). It's also why James Whistler's famous painting Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl is (appropriately) misnamed: Of course Whistler knows that he's painting and not actually composing a musical symphony - his title is metaphorical and artistic, rather than literal. To be clear, there's nothing inherently wrong with writing a book where the subject is history or biography or discography or chronology or collectibles or concert itineraries or instrumentation or orgies or anything else tangentially related to actual music. Indeed, a great many readers (often including myself) enjoy consuming this style of writing. But I focus on the literal music of popular music - how recording artists of the past several decades employ pitch and rhythm in compelling, sophisticated, and ever-evolving ways. And academia is the best place to do so. To that end, I have decided on revamping my Led Zeppelin blog into a Pop Music blog. I will analyze not only Zeppelin's music, but other pop recording artists' music, as well. I will also post summaries and reviews of articles and books by authors who have written about those “purely musical achievements”. |

Aaron Krerowicz, pop music scholarAn informal but highly analytic study of popular music. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed