|

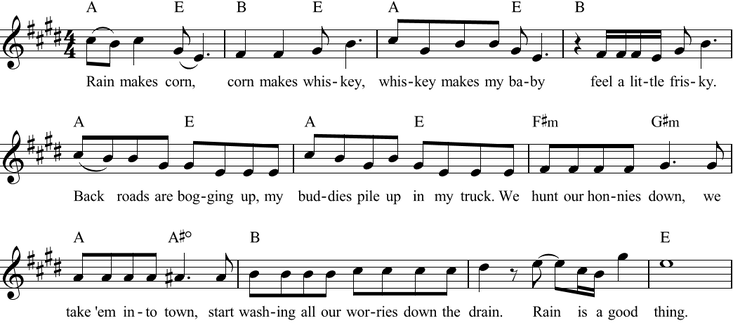

I went to the Indianapolis Indians minor league baseball game last night, in large part to see two high-ranked prospects pitch against each other: the home team's Mitch Keller (the Pittsburgh Pirates #1 prospect, and baseball's #17 overall) vs. the Louisville Bats' Vladamir Gutierrez (the Cincinnati Reds' #7 prospect). In the top of the 8th inning, Mother Nature halted play with rain. Check out this photo, which I borrowed from the Indians' official Twitter account: During the break, they played a handful of precipitation-themed songs, such as B.J. Thomas' Raindrops are Falling on My Head' (1969). As a pop music scholar and music theory teacher, I'm constantly on the lookout (hearout?) for pieces that I can use as examples in my classes, and three other tunes played last night work perfectly. In order of sophistication: 1. Luke Bryan's 'Rain is a Good Thing' (2009)... ... employs a secondary diminished chord (vii°/V) at the end of each chorus (on the word "town"). 2. Jimmy Nash's 'I Can See Clearly Now' (1972)... ... employs mode mixture by using C major (bVII) and F major chords (bIII) in D major. (Also a chromatic C# minor in the bridge, though that's not as good an example since it'd have to borrow from the parallel Lydian instead of the parallel minor.)

3. Milli Vanilli's 'Blame it on the Rain' (1989)... ... modulates constantly. The intro, prechorus, and first two choruses are all in B major; the verses are in B-flat major; the bridge is ambiguous but it sounds like A-flat major to my ears; and the final chorus and coda are in C major. It's not at all unusual for songs to change keys, but there aren't too many out there that do so three distinct times. Also highly unusually, NONE of these tonalities are closely related, which makes this an ideal example for the chapter I'll be teaching this fall on distantly-related modulation.

Maybe rain delays aren't so bad after all... :-)

1 Comment

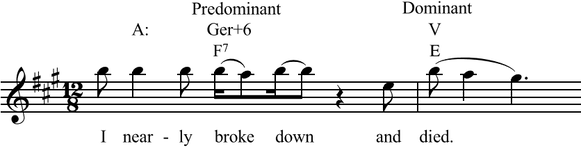

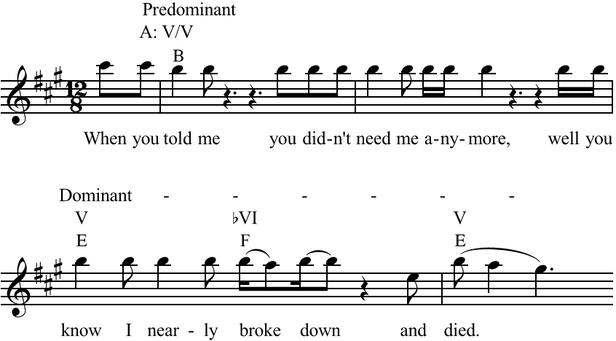

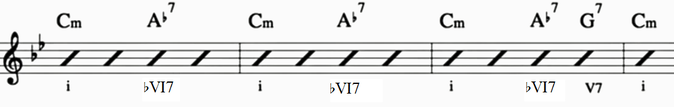

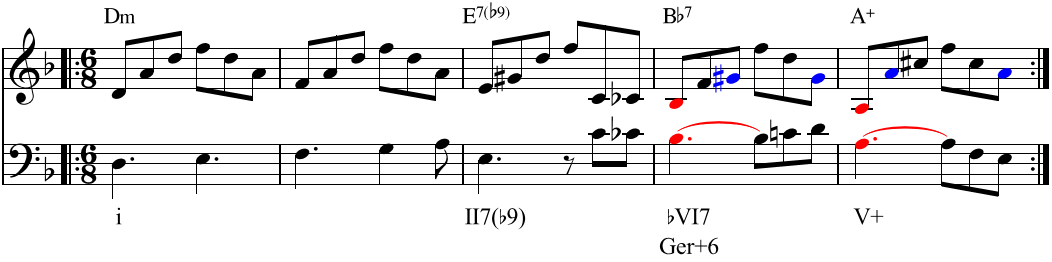

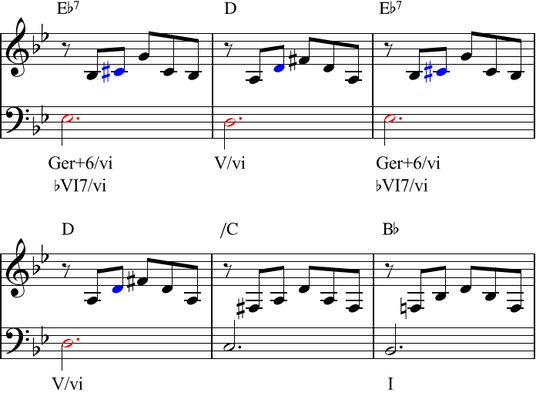

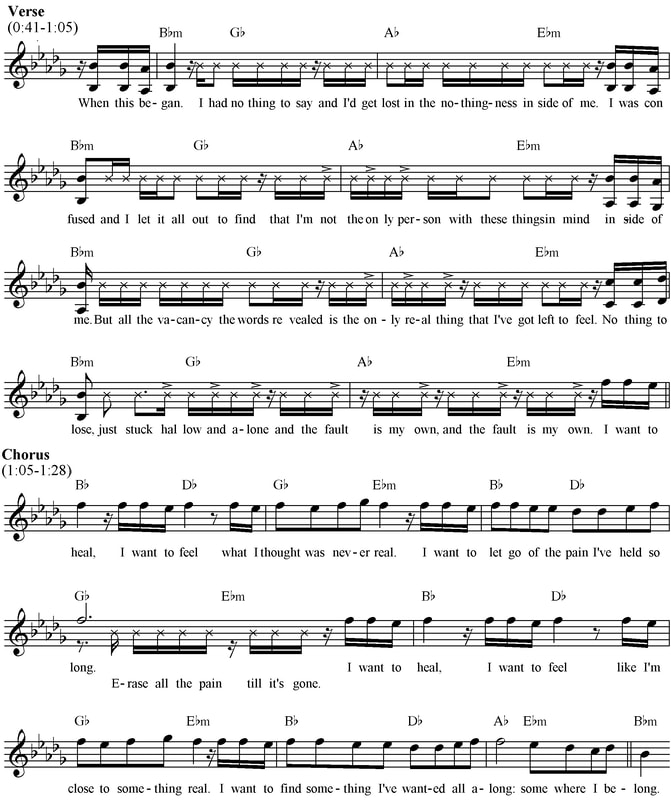

I'll be teaching Theory 3 this fall. In preparation, I've been reviewing the concepts we'll cover, and finding as many pop examples as I can to supplement the textbook's classical examples - including mode mixture, the Neapolitan chord, modulations to distantly-related keys. The next chapter is on augmented sixth chords. Though quite prevalent in the classical repertoire, there seems to be much debate over whether or not augmented sixths are used in popular music. This enthusiastic blogger insists there's one in The Beatles' 'Oh! Darling', arguing that the F7 (bVI in A major) at the end of the bridge functions as an enharmonic German augmented sixth, resolving as any good predominant should to V (in this case E). But there are two glaring problems with his interpretation. First, it's an F chord - not an F7 - which means it cannot be an augmented sixth, even accounting for enharmonics. Second, that F chord is not a predominant. Yes, it progresses to V, but it also progresses from V. So a more careful consideration of the context shows it to be a chromatic upper neighbor, and thus its function is that of a dominant prolongation instead of a predominant. (The predominant is the V/V, B major, heard in the two bars immediately preceding.) So 'Oh! Darling' clearly does not employ an augmented sixth - for multiple reasons. But what about songs where the bVI does have a seventh, and where it truly is a predominant? The following YouTube video gives four such examples. In the first example, Tom Waits' 'Dead and Lovely', he analyzes Ab7 as a Ger+6 in C minor. This is a much better example than 'Oh! Darling', but I maintain that it is not an augmented sixth. The defining characteristic of +6 chords is the voice leading of the augmented sixth resolving outwards to an octave. In this case, however, the seventh of that Ab7 (the note Gb or F#) does not resolve up to G, but rather it planes down to F (the seventh of the G7). Without the proper voice leading, I cannot justify calling the chord an augmented sixth. To do so is to over-complicate an otherwise standard progression. Here's how I would analyze the same passage, without the augmented sixth: I have the same problem (the voice leading discourages an interpretation with an augmented sixth) with the second example, 'Love in My Veins' by Los Lonely Boys. The third and fourth examples, however, do feature proper augmented sixth voice leading, and so in these two instances the +6 is (more) justified. In my transcription of The Beatles' 'I Want You (She's So Heavy)' below, the G#s resolve up to A (shown in blue), while the Bbs resolve down to A (shown in red). This is exactly how augmented sixths should resolve, thus the Ger+6 label is appropriate. The same voice leading (and color coding) is found in 'Blackout' by Muse. So in 'I Want You (She's So Heavy)' and 'Blackout', the Ger+6 interpretation is acceptable, but what advantage is there over simply calling them bVI7? In classical harmony, the augmented sixth chords (especially the Italian and French +6s) cannot be explained any other way - indeed, that's why +6s were invented: to help make sense of something that could not make sense otherwise. But in pop harmony, even the most convincing +6 chords could easily be simplified to bVI7. With nothing to gain through employing +6s in pop harmony analysis, I see no reason to use them.

Billy Joel's 'Uptown Girl' was released on his 1983 album An Innocent Man, two years before I was born. It's hard to imagine that I never heard it on the radio growing up, but the first time I remember hearing it was in the 2015 movie Trainwreck. On first listen, it appears to be a happy-go-lucky and extremely catchy pop confection - perhaps as far from a tragedy as music can get. But hear me out: After careful study, I think it is. And it begs an interesting question: Is it a tragedy if the narrator refuses to recognize and accept his own failure? It all started yesterday when I found this YouTube video discussing the song's interesting key changes. Many people who attempt to analyze and explain music on YouTube have no idea what they're talking about, but this guy actually knows his stuff. I found his insights so compelling that I decided to study 'Uptown Girl' myself. And what a fascinating piece of work it is!

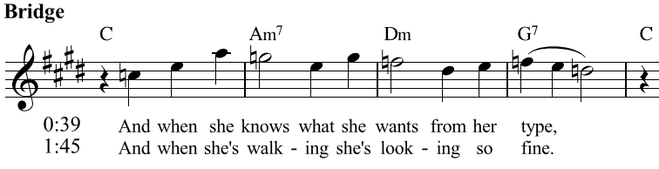

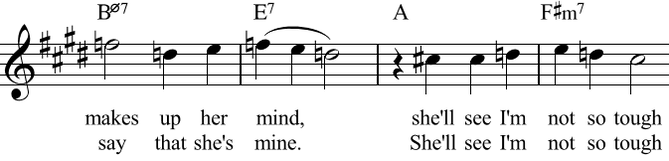

The first thing that stands out as unusual is the structure. 0:00 Intro (4) instrumental 0:09 Verse 1 (8) "... uptown world..." 0:24 Verse 2 (8) "... white bread world..." 0:39 Bridge 1 (12) "... she knows what she wants..." 1:01 Verse 3 (8) "... I've seen her..." 1:16 Break (8) "Oh" 1:30 Verse 4 (8) "... I can't afford..." 1:45 Bridge 2 (12) "... when she's walking..." 2:08 Verse 5 (8) "... white bread world..." 2:23 Break 2 (8) "Oh" 2:37 Coda "... My uptown girl..." Notice the presence of both a bridge and a break. I'm not familiar enough with Joel's work to know if this is common in his music, but I know The Beatles only did that in five (2.4%) of their 211-song official output. 'Only A Northern Song', 'Lady Madonna', 'Blackbird', 'Piggies', and 'Honey Pie' all use both bridges and breaks, but in those cases the breaks are simply instrumental iterations of the verse. The breaks in 'Uptown girl', by contrast, are musically independent from the song's other sections. And it turns out there's a good reason why Joel employs a musically independent break - it has to do with the lyrics. The song is about an affluent, high-class (uptown) woman with whom Joel is smitten. The problem is that the singer is from a less-wealthy, lower class (downtown). Reflecting this musically, the verses are all in E major, representing that higher-class, while the bridges and breaks attempts to woo her away from E major. At first, Joel tries C major ("she knows what she wants" and "when she's walking"). When that fails to get her attention, he tries A major ("she'll see I'm not so tough"). But that fails, too, as the music reverts to the uptown E major in the next verse. Not one to give up, Joel then launches into the break ("oh"), which is tonally ambiguous but contains clear tonicizations of B minor (F#7-Bm in the first ending) and B major (F#7-B in the second ending). But, once again, the attempts to overthrow the primary tonic of E major (and thus seduce this uptown girl away from her stale high-class environment) fall short as the music reverts once more to E major. Judging from this tonal conflict, Joel does NOT sweep this uptown girl off her feet. Thus, the song is a tragedy - in the end, despite his efforts, he doesn't get the girl. And yet the music video tells a different story. In this version, the woman at first walks away, rejecting Joel's advances (at 1:45, 1:58, and 2:28 - note that the timings are different for the video). But by the end of the song, she capitulates. She joins in the dancing at 2:41, and rides off with Joel on his motorcycle at 3:10.

So we, the listening audience, are given mixed signals. We hear that he doesn't get the girl, but we see that he does. Is this intentional on Joel's part? Was he trying to make an artistic statement through this conflict between what we see and what we hear? I doubt it. More likely he was just writing the best music he could, not paying much attention to the tonal narrative and entirely unaware that he had built this discrepancy into his work. The past few days I've blogged of the permanent Picardy third in Linkin Park's 'Somewhere I Belong' and 'Easier to Run', citing them as the first two songs that thoroughly convince me of the technique. But after thinking about it for a while, I realized that's not entirely true. Alanis Morisette's 'You Ought Know', from her 1995 mega-hit album Jagged Little Pill is equally convincing:

The song is clearly in F# minor - I don't see how anybody could argue otherwise - and yet the chorus consistently employs an F# major triad. It's also an excellent song to demonstrate mode mixture on IV, so I'll be using this as a homework assignment for my sophomore theory class this fall, when we get to the chapter on mode mixture.

The other day I blogged about the permanent Picardy third in the choruses of Linkin Park's 'Somewhere I Belong', and how it's the first example I've ever encountered that completely convinces me of the concept. This morning I found the second example that convinces me: 'Easier to Run', four tracks later on the same album. In this case, the mode mixture packs a visceral punch at the onset of each chorus, which compellingly conveys the emotional trauma of the lyrics. This is first-rate songwriting!

This fall I will be teaching a section of Music Theory 3, in which we will cover the Neapolitan chord. In common-practice classical harmony, the Neapolitan is almost always used in first inversion and functions as a predominant (it leads to V). But in pop music, it is almost always in root position and functions as an upper leading tone to tonic (it leads to I). And that's exactly how Linkin Park employs the Neapolitan in 'Don't Stay', the second track of their 2003 album Meteora. The song is in B minor, with prominent C major (Neapolitan) chords throughout the verses and at the end of the bridge. Here's a handout based on this song that I'll go through with my students in class. I'll play the whole song for them and have them analyze using Roman Numerals, and then circle all the Neapolitan chords.

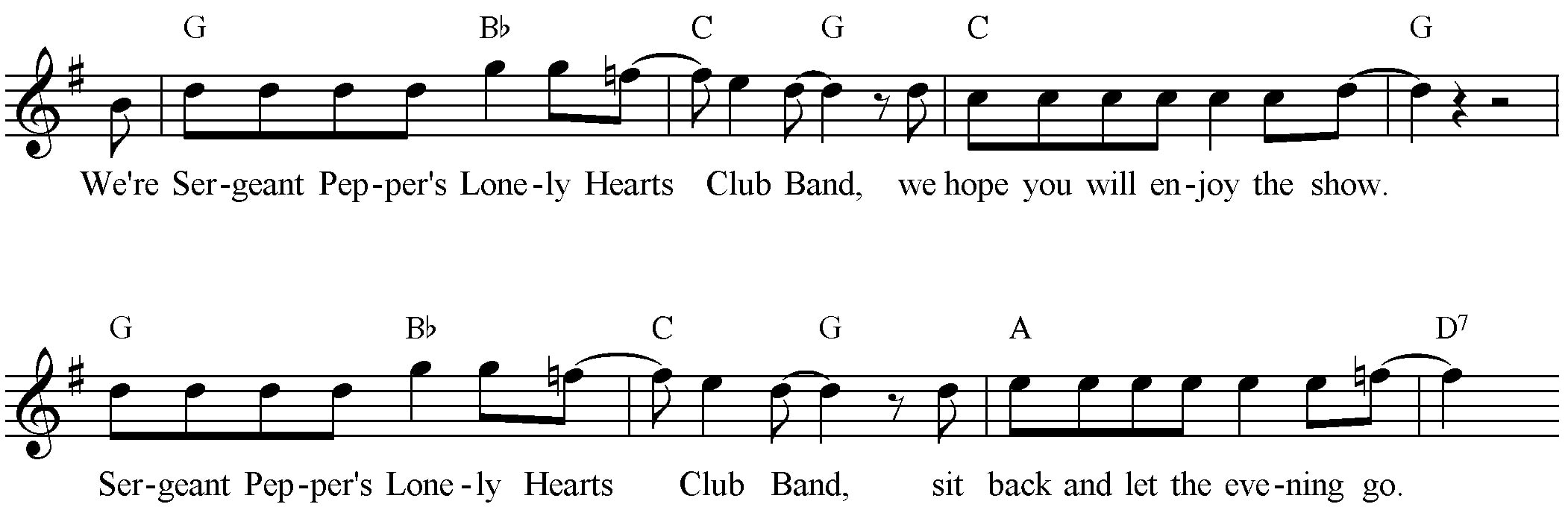

In his book Everyday Tonality, Philip Tagg proposes the concept of a "permanent Picardy third": One of the most common alterations in non-classical tertial harmony is to raise the third of tonic triads in minor modes. ... Such alteration can be understood in terms of a tierce de Picardie used constantly throughout a piece of music as substitute for the tonic minor triad (p. 274-275). The title track to The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band is a good example. Tagg would argue that this song is in G dorian with a permanent Picardy third. But I have never liked this interpretation. I don't see what's wrong with calling this G major with a bIII (B-flat major) thrown in for a little harmonic color and spice. Yes, B-flat isn't in the key of G major - and ya know what? That's okay! The permanent Picardy strikes me as the musical equivalent of literature's "unreliable narrator", in which a story is told from a compromised perspective. In music, the tonic triad determines whether the composition in major or minor. To argue otherwise is to adopt an "unreliable tonic" principle that seems to me like a theorist who is trying too hard to have something meaningful to say! But then this morning I discovered the song 'Somewhere I Belong', the third track from Linkin Park's 2003 album Meteora. In this case, the song is CLEARLY in B-flat minor (I don't see how anybody could argue with that), and yet the tonic triad in the chorus is consistently major. It's the first example I've ever encountered that thoroughly convinces me of Tagg's "permanent Picardy" concept. So while I'm still skeptical of the principle, and while I vehemently disagreement with Tagg's assertion that the permanent Picardy third is "one of the most common alterations", there are compelling examples out there - you just have to look pretty hard to find them!

|

Aaron Krerowicz, pop music scholarAn informal but highly analytic study of popular music. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed