|

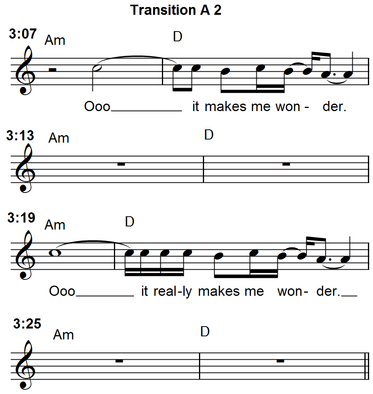

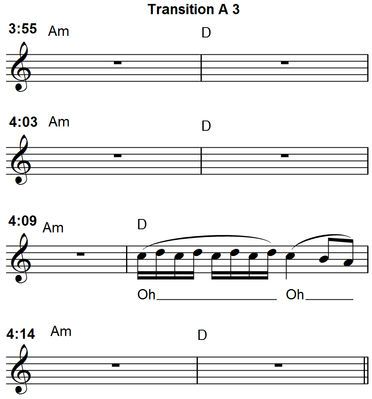

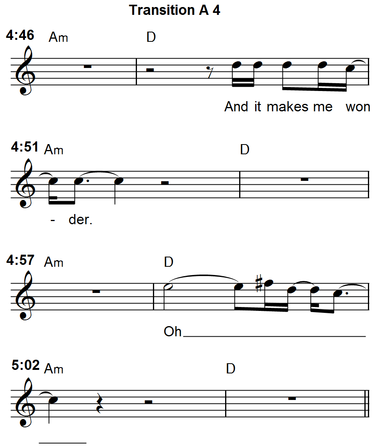

There are two different transitions in 'Stairway to Heaven'. The first, which I call "Transition A", is heard a total of four times. The second, "Transition B", is heard only once. I've blogged about both transitions before - Transition A was part of my rhythmic displacement series, and I compared the rhythmic instability of Transition B to The Beatles' 'Here Comes The Sun' in another post. All four Transition As consist of four phrases, each comprised of identical two-measure harmony (a-D). What's different about the total 16 phrases (four Transition As x 4 phrases each = 16 total phrases) are Robert Plant's vocals. Five of those 16 phrases include the line "makes me wonder" while the remaining nine are instrumental. (NOTE: There are two phrases where he sings "Oh", but I'm counting those as instrumental.)  2:15-2:40 Transition A 1 (8 measures) 2:15 (c) |a |D | “Makes me wonder...” (beat 4) 2:21 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 2:27 (c) |a |D | "Makes me wonder..." (beat 2) 2:34 (c) |a |D | [instrumental]  3:07-3:31 Transition A 2 (8 measures) 3:07 (c) |a |D | “Makes me wonder...” (beat 2) 3:13 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 3:19 (c) |a |D | "Makes me wonder..." (beat 2) 3:25 (c) |a |D | [instrumental]  3:55-4:20 Transition A 3 (8 measures) 3:55 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 4:03 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 4:09 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 4:14 (c) |a |D | [instrumental]  4:45-5:08 Transition A 4 (8 measures) 4:45 (c) |a |D | "Makes me wonder..." (beat 4) 4:51 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 4:57 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 5:02 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] The final transition, the only iteration of Transition B, is quite different from Transition A, and particularly interesting.

5:35-5:56 Transition B 1 (8 measures) 5:35 (f) |Dsus4 |D |C | | [instrumental] 5:46 (f') |Dsus4 |D |C |G/B | [instrumental] But I've already considered this Transition B in a previous blog, so there's no need to repeat it here.

0 Comments

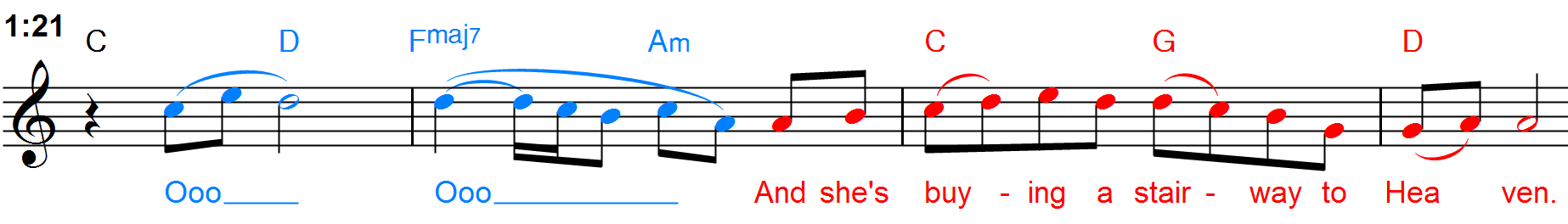

I've already written about the first verse of 'Stairway to Heaven' in my series on rhythmic displacement, so I'll consider it only briefly here. The first verse is structurally identical to the instrumental introduction. Both employ four phrases, each four measures long, the first two of which are identical, the last two of which are comparable and so labeled (b) and (b'). Most interesting is that Plant's second verse ("There's a sign...") begins early, at 1:34, overlapping with the fourth and final phrase of the first verse. 0:54-1:48 (A) Verse 1 (16 measures) 0:54 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | “There's a lady...” 1:07 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | “When she gets...” 1:21 (b) |C D |FM7 a |C G |D | “Ooo...” 1:34 (a & b') |C D |FM7 a |C D |FM7 | “There's a sign...” Part of me wants to label the third and fourth phrases as their own distinct section. I could see this as a bridge instead of part of the verse. But bridges are defined by contrast to the verses, and while there certainly is some contrast, there is also a lot of similarity. The first four chords of the phrase in question (C-D-FM7-a) are the same as the last four chords of the previous phrases. The harmonic rhythm is faster (covering two measures instead of three), and the chords are all in root position (no inversions this time), but there is a clear and strong harmonic similarity. Now, there are many songs where the verses and bridges share strong harmonic similarities but there are other differences, such as melody, that distinguish the two sections. But in 'Stairway', there is also a clear and strong melodic similarity. While the first half of the phrase in question is different (“Ooo...”, shown below with blue notes), the second half employs the same pattern as the previous phrases. They even use the same lyrics (“and she's buying a stairway to heaven”, shown in red). Finally, the lyrics suggest that these (b) phrases are not a bridge because they include the title (which was also heard earlier in the first phrase of verse 1). While it's not unheard of for the title to be lifted from the bridge (check out 'She's A Woman', 'Rain', or 'For No One' by The Beatles), it is rather rare. It's much more common for the title to be lifted from verse lyrics than from bridge lyrics. So all of this compels me not to label it as a bridge, but as part of the verse. The contrast that is there isn't strong enough to justify an independent formal level label Verse 2 is half as long as verse 1, and it's identical to the first half of verse 1 (save for the lyrics).

1:48-2:15 (A') Verse 2 (8 measures) 1:48 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | “In the tree...” 2:01 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | [instrumental] The reason for this abbreviation is because we've heard the (a)(a)(b)(b') pattern twice already (once from 0:00-0:54 as the intro, then again from 0:54-1:48 as the first verse). To avoid any threat of monotony, this third iteration (and every subsequent iteration) is curtailed to two phrases. This truncated second verse leads to the first transition, which I'll consider tomorrow. Having completed the overview, we now turn to the individual sections for a more detailed look.

At their most fundamental, introductions set up what comes next. This almost always means the music heard in the intro will be heard again later in the song. And 'Stairway to Heaven' is no exception. The instrumental introduction of 'Stairway' consists of four phrases, the first two of which are essentially identical and the second two of which are comparable. 0:00-0:54 (A) Introduction (16 measures) 0:00 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | [instrumental] 0:14 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | [instrumental] 0:27 (b) |C D |FM7 a |C G |D | [instrumental] 0:40 (b') |C D |FM7 a |C D |FM7 | [instrumental] The (a) phrases are heard a total of six times: twice each in the introduction, first verse, and second verse. 0:00 (a) Intro [instrumental] 0:14 (a) Intro [instrumental] 0:54 (a) Verse 1 “There's a lady...” 1:07 (a) Verse 1 “When she gets there...” 1:48 (a) Verse 2 “In the tree...” 2:01 (a) Verse 2 [instrumental] The (b) and (b') phrases are heard a total of four times: twice each in the intro and first verse. 0:27 (b) Intro [instrumental] 0:40 (b') Intro [instrumental] 1:21 (b) Verse 1 “Ooo...” 1:34 (b') Verse 1 “There's a sign...” It's worth noting how both the (a) and (b) phrase are only used in pairs – they never once appear as a single phrase. It's also worth noting how the (a) and (b) phrases are used together in the intro and first verse, but the second verse uses only the (a) phrases. We'll address why that is in a subsequent blog. Earlier, I blogged about organic development in 'Good Times Bad Times'. It's an extremely sophisticated song, at least from a structural standpoint. There's no way they could top that, right? WRONG – They were just getting started! If you thought the organic development and structure of 'Good Times Bad Times' was sophisticated, then the expanded and elaborated use of both in 'Stairway to Heaven' will blow your mind. Now, many people before me have analyzed 'Stairway', and the vast majority of them strike me as deeply problematic. Most analyses oversimplify by differentiating sections that are clearly and strongly related. This robs the music of its organic development. Others try to over-complexify (I'm might be making up that word), as if their spectacularly arcane analysis will somehow make the music better. Yes, this is an extremely sophisticated (and to my knowledge unique) design for a song, and so it absolutely requires analysis that does justice to its nuances. But I have major problems when analyses are more complicated than the subject being analyzed. The point of analysis is to better understand that which is being analyzed. And if the analysis is more thorny than the subject, then that analysis only inhibits rather than facilitates understanding. The trick, then, is balance – don't make the analysis so simple that it misses the musical sophistication, but don't make it unnecessarily complicated, either. With that caveat in mind, here's my take on 'Stairway to Heaven'. 0:00-0:54 (A) Introduction (16 measures) 0:00 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | [instrumental] 0:14 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | [instrumental] 0:27 (b) |C D |FM7 a |C G |D | [instrumental] 0:40 (b') |C D |FM7 a |C D |FM7 | [instrumental] 0:54-1:48 (A) Verse 1 (16 measures) 0:54 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | “There's a lady...” 1:07 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | “When she gets...” 1:21 (b) |C D |FM7 a |C G |D | “Ooo...” 1:34 (a & b') |C D |FM7 a |C D |FM7 | “There's a sign...” 1:48-2:40 (A') Verse 2 (8 measures) 1:48 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | “In the tree...” 2:01 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | [instrumental] 2:15-2:40 Transition A 1 (8 measures) 2:15 (c) |a |D | “Makes me wonder...” 2:21 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 2:27 (c) |a |D | "Makes me wonder..." 2:34 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 2:40-3:31 (B) Verse 3 (17 measures) 2:40 (a & d) |C G |a |C G |a | “There's a feeling...” 2:52 (a & d') |C G |a |C G |a |C G | “In my thoughts...” 3:07-3:31 Transition A 2 (8 measures) 3:07 (c) |a |D | “Makes me wonder...” 3:13 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 3:19 (c) |a |D | "Makes me wonder..." 3:25 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 3:31-3:55 (B) Verse 4 (9 measures) 3:31 (a & d) |C G |a |C G |a | “And it's whispered...” 3:42 (a & d') |C G |a |C G |a |C G | “And a new day...” 3:55-4:20 Transition A 3 (8 measures) 3:55 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 4:03 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 4:09 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 4:14 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 4:20-4:45 (C) Verse 5 (9 measures) 4:20 (d & e) |C G |a |C G |a | “If there's a bustle...” 4:31 (d & e') |C G |a |C G |a |C G | “Yes, there are two paths...” 4:45-5:08 Transition A 4 (8 measures) 4:45 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 4:51 (c) |a |D | "Makes me wonder..." 4:57 (c) |a |D | [instrumental] 5:02 (c) |a |D | "Makes me wonder..." 5:08-5:35 (C) Verse 6 (9 measures) 5:08 (d & e) |C G |a |C G |a | “Your head..” 5:19 (d & e') |C G |a |C G |a |C G | “Dear lady...” 5:35-5:56 Transition B 1 (8 measures) 5:35 (f) |Dsus4 | D |C | | [instrumental] 5:46 (f') |Dsus4 | D |C |G/b | [instrumental] 5:56-6:45 (D) Solo (20 measures) (g) |a G |F | x10 6:45-7:47 (D) Verse 7 (18 measures) 6:45 (g) |a G |F | “As we wind...” 6:50 (g) |a G |F | “Our shadows...” 6:54 (g) |a G |F | “There walks...” 6:59 (g) |a G |F | “Who shines...” 7:04 (g) |a G |F | “How everything...” 7:08 (g) |a G |F | “And if you listen...” 7:13 (g) |a G |F | “The tune will come...” 7:18 (g) |a G |F | “When all are...” 7:22 (g) |a G |F | “To be a rock...” 7:47-8:02 Coda “And she's buying...” With the overview complete, it's time for a detailed look at each of the individual component parts that comprise the song. I plan to dedicate one blog to each section over the next week or two.

We've already seen how 'Dazed and Confused' and 'Houses of the Holy' displace one beat (though in opposite directions), how 'When the Levee Breaks' displaces one measure, and how 'Stairway to Heaven' displaces by two beats and by an entire phrase. Next and last in this series is a song that displaces half a beat: 'Black Dog', the initial track of Led Zeppelin IV (1971). In this case, a seven-note pattern lasting nine eighth notes... ...is repeated over common time measures, yielding rhythmic displacement of a single eighth note (half a beat) per iteration. Lesser musicians might have repeated these musical ideas more or less the same each time. But Zeppelin, ever attentive to detail, found ways to subtly alter their music in a way simultaneously familiar yet different through rhythmic displacement. And that, I suspect, is one trait (of many) that separates the good bands from the great bands.

Last Sunday, I blogged about the rhythmic displacement of Robert Plant's 'When the Levee Breaks' vocals through Plant starting the fourth verse at the "wrong" time (a measure late, in that case). I concluded that blog by writing, "Since the underlying harmony throughout the verses is static, this rhythmic displacement does not cause any harmonic problems the way such a displacement would in, say, 'Babe I'm Gonna Leave You' or 'Stairway to Heaven' where the harmonies are more fluid." And yet I just discovered the other day that Plant does use that same "start at the wrong time" displacement technique in 'Stairway to Heaven' - not one measure late, like 'Levee', which certainly would cause clashes with the underlying harmony, but rather an entire phrase early (in this case, four measures).

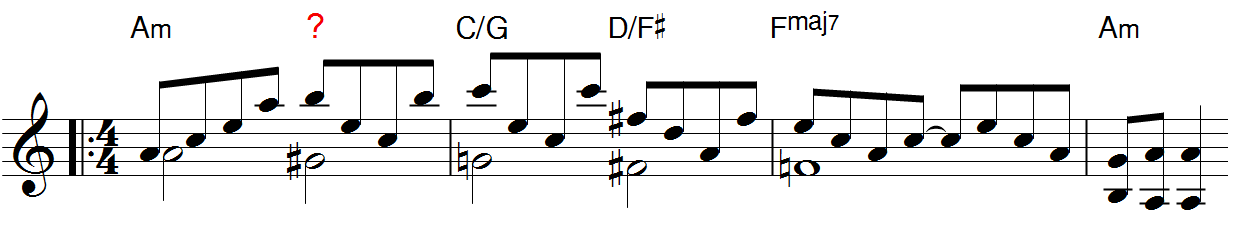

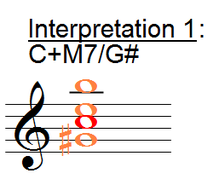

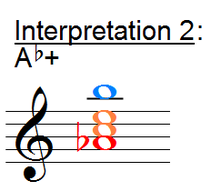

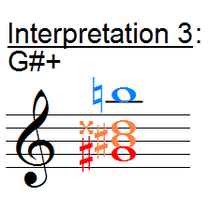

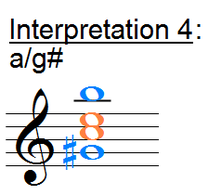

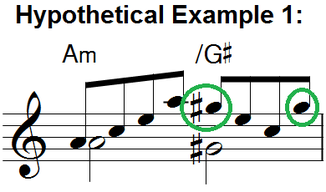

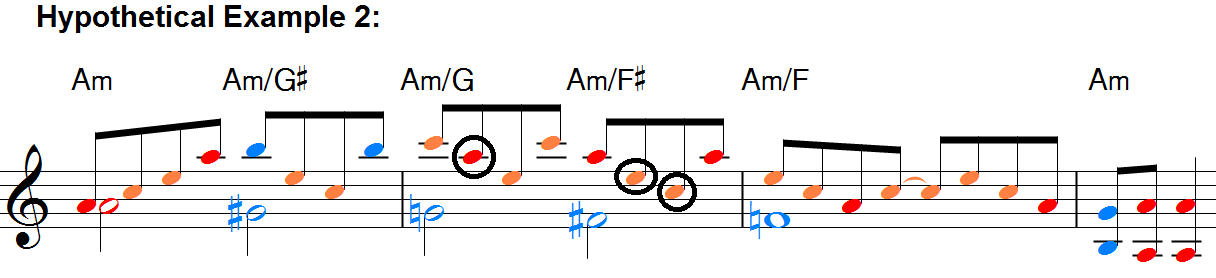

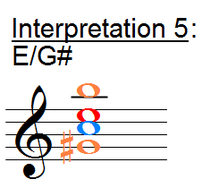

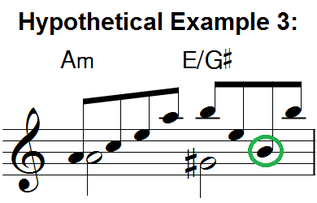

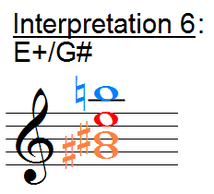

The instrumental introduction establishes a four-square phrase pattern (four phrases, each four measures long). The first and second phrases are identical, so they're both labeled (a). And the third and fourth phrases are nearly identical, so they're labeled (b) and (b'). 0:00-0:54 Instrumental Introduction (16 measures) 0:00 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | 0:14 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | 0:27 (b) |C D |FM7 a |C G |D | 0:40 (b') |C D |FM7 a |C D |FM7 | Plant's entry marks the start of the first verse at 0:54. That verse employs identical four-square harmony as the introduction. The first phrase (0:54) corresponds to the lyrics "There's a lady...", the second phrase (1:07) to "When she gets..." Though the lyrics are different, the pitches and chords to which those lyrics are sung are essentially identical - the same melody and harmony are repeated, just with different words. That should come as no surprise as it is EXTREMELY common in all genres of pop music The third phrase (1:21), being harmonically different from the first two, has a correspondingly different sung melody (though the ending is quite similar). The fourth phrase (1:34) is where things get really interesting. As was the case in the intro, the harmonies of the fourth phrase are comparable to the third phrase. Yet Plant's singing is comparable to the first and second phrases. This means that melodically the fourth phrase should be labeled (a), but harmonically it should be labeled (b'). In other words, there's a certain "divorce" between the melody and harmony. (And yes, I completely understand the connotations of that term in the context of popular music scholarship, and how I'm using it differently than other scholars.) 0:54-1:48 Verse 1 (16 measures) 0:54 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | “There's a lady...” 1:07 (a) |a E/g# |C/g D/f# | FM7 |a | “When she gets...” 1:21 (b) |C D |FM7 a |C G |D | “Ooo...” 1:34 (a & b') |C D |FM7 a |C D |FM7 | “There's a sign...” Plant "should" have repeated the tune of phrase three ("Ooo...") to match the harmony, saving "There's a sign..." for the start of the second verse (at 1:48). Instead, he displaces that entry by starting verse 2 a full phrase (four measures) early, overlapping with the concluding phrase of the first verse. Just over one year ago, I visited the Biedenharn Museum and Gardens in Monroe, Louisiana with my good friends Jude and Rande Kessler. As part of the museum tour, we walked through the old Biedenharn household, where the family's piano remains in working condition in the front room. The guide invited us to play, so I sat down and ran through the opening passage of “Fur Elise” by Beethoven. “That was really impressive,” Rande enthused. "Naw," I honestly demurred, "it's the kind of thing that people recognize, so when they hear it they think you're really good even when you're not!" After chuckling, Rande continued, "Sure. 'Fur Elise' is to the piano what 'Stairway to Heaven' is to the guitar." Indeed, the opening line of “Stairway” has to be among the most famous and frequently played guitar passages in history. It's such a cliché that I've heard people joke about being banned from guitar stores for playing it! One reason this passage is so famous is the mysterious second chord (heard on beat 3 of the first measure, marked with a question mark in the example above), which has long puzzled analyzers. Much like the opening chord of "A Hard Day's Night", the mystery of this harmony has contributed to its enduring legacy. I see six different interpretations, all of which have different strengths and weaknesses and will be considered below. Ultimately, it comes down to (1) which tone is the root?, and (2) which tones are part of the chord vs. which are non-chord tones? In the examples below, the chord tones are shown in orange (with the root in red), while non-chord tones are shown in blue. Interpretation 1: C+M7/g# This means that all four tones are part of the chord – there are no non-chord tones. Strength: It accounts for all tones present. This is the most literal interpretation. Weakness: This is a case of an analysis being over-complicated. My verdict: I don't buy it. Technically, yes, this is accurate – it is indeed a second inversion C augmented chord with an added major seventh. But this is one of those interpretations that satisfies the head while leaving the heart cold. I just don't feel it this way. If I have to give a more objective explanation, it's the root movement from A to C. I don't hear it like that, even if it is technically correct. Interpretation 2: Ab+ This means reinterpreting the G-sharp as A-flat, and calling the high B a passing tone. Strength: One of the most important characteristics of this progression is the chromatically descending bass line. Interpreting the second chord as an A-flat augmented retains that salient chromatic descent in the chord roots. Weakness: One of my professors at Boston University, Dr. Martin Amlin, once made an argument for why descending lines should use sharps instead of flats – it's because of voice leading. In this case, A-flat has no business in the key of A minor. But G-sharp (even though it's the same note as A-flat, just spelled differently) does belong in A minor as the leading tone. (That's why Interpretation 3 below is a G-sharp augmented.) On the other hand, Dr. Amlin was referring to classical contexts - not pop, where rules like voice leading are much more flexible. My verdict: I could buy in to this interpretation, despite its voice leading concerns, but I don't because I think there's a better solution. Interpretation 3: G#+ This means the C is actually a B-sharp, and the E is actually a D-double-sharp. Oh, and the high B is still a passing tone. Strength: This avoids the voice leading problem of interpretation 2. Weakness: Double sharp?! WTF, mate? My verdict: This solves one problem (that doesn't really need to be fixed) at the expense of creating several other (and far worse) problems. Like Interpretation 1, this is another example of the analysis being more complicated than the subject, which defeats the purpose of analysis. No way, Jose! Get this outta here! Interpretation 4: a/g# This means the entire measure is fundamentally a tonic A minor chord, thus the high B is a passing tone while the G-sharp in the bass is either a passing tone or a line chromatic. Strength: It's certainly the simplest of the interpretations because there's only one chord (instead of two) to account for. Weakness: There's no root. My verdict: While I often use this choice when analyzing Beatles music, I don't find it appropriate in this context, in part because of the high B. If a G# replaced that B.... ... or if the subsequent chords clearly sustained A minor (in which case one could call this whole passage a static A minor chord with line chromatics in the bass)... … then I'd probably chose this interpretation for the sake of simplicity. As is, however, I still think there's a better solution. Interpretation 5: E/G# This means the C is a pedal tone left over from the previous A minor chord. Strength: The progression A minor to E major is extremely common. This root movement makes perfect sense. Weakness: That pesky C complicates things. The only way to account for it is as a suspension leftover from the previous chord. My verdict: I think this is the best interpretation. If we make another hypothetical example, this one in which the non-chord tone C is replaced by chord tone B... … not only does it look good, but it sounds good, too. Jimmy Page could have easily played this instead, though he chose not to. And frankly, he shouldn't have played this - the progression is much more interesting with ambiguous harmony. Interpretation 6: E+/G# This solves the problem of that pesky C by reinterpreting it as a B-sharp (the fifth of an E-augmented chord); however, that only creates a new problem regarding the high B, which now necessarily becomes a non-chord tone. Strength: It solves one problem... Weakness: … by creating another. My verdict: Bottom line is there's nothing to be gained from this interpretation. Any potential gains are offset by additional complications. Clearly, there is no easy answer, but I find Interpretation 5: E/G# most compelling.

Another simple example of rhythmic displacement can be heard in “Houses of the Holy”, the fourth track of Physical Graffiti (1975). In this case, rhythmic displacement is built in to the main riff and so repeated frequently throughout the song. A three-beat pattern is first played on beat one, then immediately following on beat four. This syncopated phrasing helps give the track its funky character.

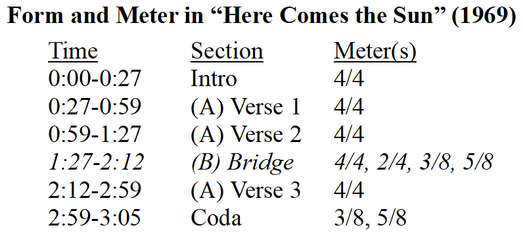

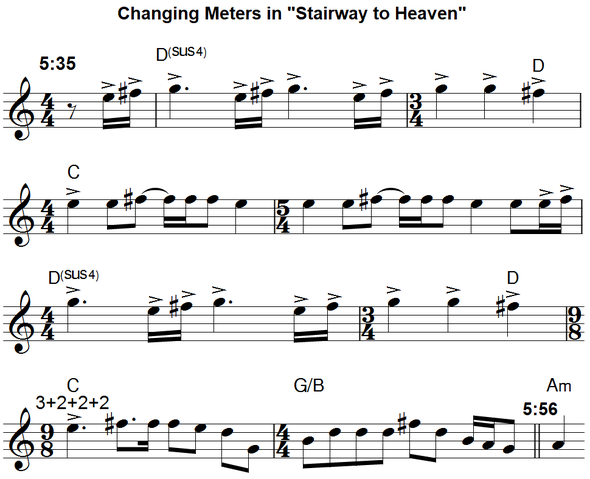

I've looked at rhythmic displacement in Led Zeppelin's music through several previous blogs. Another rhythm trick Zep loves is changing meters. And this, I suspect, also shows how Zeppelin's music grew out of The Beatles' music because The Beatles also love changing meters. Several John Lennon songs like “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Happiness is a Warm Gun” are good examples, but it's in the hands of George Harrison that The Beatles took this technique to extremes. Back in 2014 I blogged about the rhythmic sophistication of “Here Comes the Sun”, and in 2016 I created a BEATLES MINUTE video based on the same concept. It's significant that these constantly changing meters are used in the bridge – NOT in the verses – because the rhythmic instability accentuates the sense of arrival with the subsequent verse, which goes back to the rhythmically stable meter of 4/4 at 2:12. It's a technique many composers – both popular and classical – have employed. And Led Zeppelin does something similar in “Stairway to Heaven”.

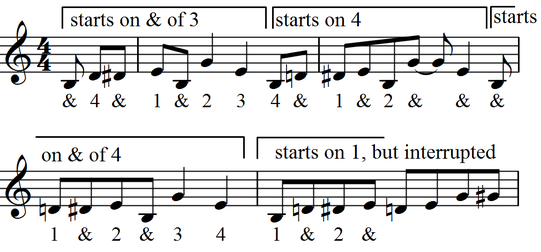

While the structure of “Stairway” is far more sophisticated than “Here Comes the Sun” (something I'll be blogging about in detail in the next few days), it features a similar climactic arrival at 5:56, right as Jimmy Page launches into his epic guitar solo. And, just like “Here Comes the Sun”, that arrival is emphasized through the use of changing meters immediately prior. After two rather substantial examples of rhythmic displacement in “Dazed and Confused” and “When the Levee Breaks”, the next two examples will be comparatively lite. In “Stairway to Heaven”, the fourth track of Led Zeppelin IV (1971), Robert Plant sometimes displaces his vocals by two beats during the lyrics “it makes me wonder”. That phrase is heard a total of five times. Since Plant takes some rhythmic liberties between iterations, we'll look at the placement of the word “make” to ensure a fair comparison. In the first and fifth times (at 2:15 and 4:46), “make” falls on beat 4 (highlighted in red in the examples above). But in the second, third, and fourth times (2:27, 3:07, and 3:19), “make” falls on beat 2, (highlighted in blue).

|

Aaron Krerowicz, pop music scholarAn informal but highly analytic study of popular music. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed