|

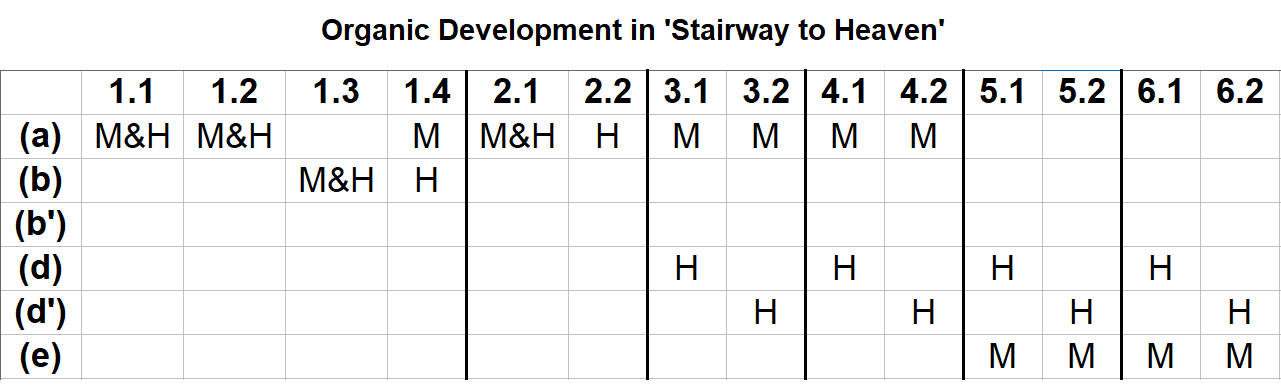

Having looked at each section of 'Stairway to Heaven' in detail, now we can draw conclusions and address why it's one of the greatest achievements in rock history. My answer to why it's so great is its organic development – the way the melody and harmony of the verses grow out of what came before, continuously blending old material with new material. This graph illustrates: The x axis indicates the verse # and phrase #, separated by a period (ex: 1.4 means verse 1, phrase 4; 3.1 means verse 3, phrase 1). The y axis refers to the phrases. M = melody H = harmony So the melody and harmony are together for the first three phrases of the first verse, and the first phrase of the second verse, but they are split for the fourth phrase of the first verse, and all of the third through sixth verses. It is that split that allows for organic development. Because when the harmony uses the new (d) phrase in verse 3, the melody simultaneously keeps the (a) phrase. Then in verse 5, the melody uses the new (e) phrase, while the harmony simultaneously keeps the (d) harmonies. Each step grows out of what came before by incorporating something new while also retaining something old. The fundamental goal for any composer is to keep the material familiar and internally consistent enough so that it clearly belongs together, but different enough to avoid monotony. A succession of unrelated material will appear disjointed and confusing, while a succession of unchanging material will become predictable and boring. Compositional skill is in large part the ability to balance the two. And one of the best ways to strike that balance is through structure. Indeed, the organic growth and structure of 'Stairway to Heaven' strikes that balance as well as any piece of music I've ever encountered.

0 Comments

Continuing the organic development we saw in verse 3, verse 5 retains the (d) harmonies while simultaneously introducing the new (e) melody. 4:20-4:45 (C) Verse 5 (9 measures) 4:20 (d & e) |C G |a |C G |a | “If there's a bustle...” 4:31 (d' & e) |C G |a |C G |a |C G | “There are two paths...” Verse 6 is identical to verse 5, just with different lyrics.

5:08-5:35 (C) Verse 6 (9 measures) 5:08 (d & e) |C G |a |C G |a | “Your head...” 5:19 (d' & e) |C G |a |C G |a |C G | “Dear lady...” Verse 3, like verse 2, contains two phrases. Those phrases are identical except that the latter is extended by a single measure (five bars long instead of four). Both reprise the (a) melody from the first and second verses, but with new (d) harmonies. 2:40-3:31 (B) Verse 3 (9 measures) 2:40 (a & d) |C G |a |C G |a | “There's a feeling...” 2:52 (a & d') |C G |a |C G |a |C G | “In my thoughts...” This third verse cannot be called a new section because it brings back an old melody. But it also cannot be called an old section, either, because the chords are new. So it's half new, half old. This is a technique known as organic development because the music grows out of what came before, just like a seed sprouts and flowers. I analyzed the organic development of 'Good Times Bad Times' earlier. This is the same technique, but on a much grander scale. While Verse 3 is the first time those (d) harmonies are used, they will be heard again six more times (two each in verses 4, 5, and 6): 3:31 (d) Verse 4 3:42 (d') Verse 4 4:20 (d) Verse 5 4:31 (d') Verse 5 5:08 (d) Verse 6 5:19 (d') Verse 6 Verse 4 is identical to verse 3, just with different lyrics.

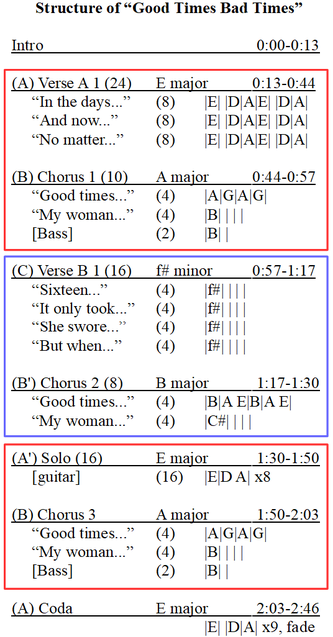

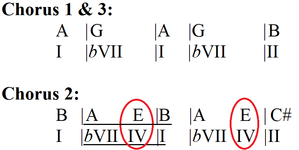

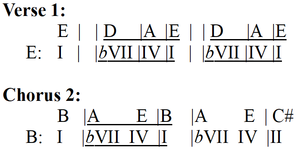

3:31-3:55 (B) Verse 4 (9 measures) 3:31 (a & d) |C G |a |C G |a | “And it's whispered...” 3:42 (a & d') |C G |a |C G |a |C G | “And a new day...” I started the analytical (as opposed to the introductory) part of the blog yesterday with a structural analysis of “Whole Lotta Love”. In it, I implied that early Zeppelin songs illustrate how they grew out of their predecessors like The Beatles. That is true to a certain extent, but that's not entirely true. I oversimplified a bit. Of course there are exceptions. And as evidence to the contrary, I present a structural analysis of “Good Times Bad Times”, the opening number of Zeppelin's 1968 self-titled debut album, which has a unique (to my knowledge, anyway) formal design. Get a load of this oddity!: Okay, so, the first thing to notice is that there are two distinct verses, here labeled Verse A and Verse B. While The Beatles occasionally employed multiple different verses within the same song (check out “Glass Onion” or “Lovely Rita”), it's rare. I don't know other bands' oeuvres well enough to cite a non-Beatles example off the top of my head, but I'm sure there are examples to be found. Some scholars have debated with me over the justification for using multiple verses instead of other labels. “Rita”, for example, is often analyzed as using verses and bridges instead of multiple verses. I certainly see the point, but I maintain these are all verses for reason I won't get into here. In any case, “Good Times” definitely uses multiple verses because each section in question is paired with a chorus – exactly what would be expected of verses. The second thing that stands out is that the chorus also has two different iterations. The distinction here is harmonic: The first and third choruses are in A major, while the second is in B major. This middle chorus grows organically out of what was heard in the first chorus as it adds an E chord (IV) on the third beats of the second and fourth measures, circled red in the example below. This addition results in a double plagal cadence (A-E-B, bVII-IV-I, underlined below) from the second to third measures. This ties in to the harmony of the initial verse (shown in the example below), which also employs double plagals but in E major (D-A-E) and twice as long (four measures where the same pattern in the chorus lasts only two). Also, the middle chorus elucidates the tonality of the outer choruses. The first and third choruses are harmonically ambiguous on their own – are they really in A major? We don't necessarily have enough information to make that claim - there are no cadences to confirm such a conclusion. But the addition of those double plagals in the middle chorus implies that the harmony of the first and third can be interpreted as “incomplete double plagal cadences” which are missing the IV chord. With that in mind, we can indeed infer that the outer choruses are in A major.

One last thing about the choruses: The middle iteration is abbreviated. While the first and third choruses both feature a two-bar bass transition, the second chorus omits it. This further differentiates the choruses, which strengthens the eventual conclusion (see below) that "Good Times" is a compound ternary structure. Finally, the solo replaces a verse. It employs identical harmonies, but rhythmically halved. This, too, grows organically out of what preceded it. The solo also uses double plagal cadences, just like the first verse and second chorus. It uses the tonality of the verse's double plagals (D-A-E) but with the chorus's rhythms (two measures instead of four). So the solo is related to both the first verse (through tonality) and to the second chorus (through rhythm). The overall structure of “Good Times Bad Times”, then, is a hybrid AB|CB'|A'B – it's part compound simple (an AB x3 in which the middle AB is actually a CB') and part compound ternary (ABA'). If I had to pick one of those designations, I think the latter more accurately and precisely articulates the form. Even though this song is from Zep's first album, it shows a spectacularly advanced hybrid formal structure and organic development that breaks with their predecessors' work (to the extent of my knowledge). It certainly would not be the last time they would use such a sophisticated musical design. |

Aaron Krerowicz, pop music scholarAn informal but highly analytic study of popular music. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed