|

I discovered the late-night radio talk show Loveline, with Adam Carolla and Dr. Drew Pinsky, just before Christmas 1999. I was in eighth grade and starting to assert personal independence. With the benefit of hindsight, it's difficult to overestimate how important that discovery was because hearing frank and explicit discussion of sexual matters helped me realize, understand, and accept my own maturation process, both physical and mental. I suspect I'd be a very different person today had I not randomly encountered that broadcast while scanning the radio dial that night. Like many adolescents, I used musical preference as a way to establish an identity, or at least the beginnings of an adult identify. I suspect many of a certain age connect The Beatles with this process, one major reason they're still so popular a half-century later. And Loveline would frequently feature guests, including many pop bands who were promoting their recent records. One night, I turned on the radio and heard for the first time a band called Stone Temple Pilots. They played a song called 'Sour Girl' from their 1999 album No. 4, which immediately captivated my 14-year-old ears. Fast forward 19 years, and I've forgotten about 'Sour Girl' - but not about Loveline. A while back, I discovered the website www.lovelinetapes.com, which contains exhaustive archives of Loveline shows. In a nostalgic bid, I decided to listen to the entire archive in chronological order. And the other night I stumbled upon that same broadcast with STP that I heard two decades ago, including its performance of 'Sour Girl' (and now I even know the exact date: 10 May 2000). This time, my musically-trained 33-year-old ears heard all sorts of new and fascinating musical subtleties that my eighth-grade ears were too inexperienced to notice. And so I set out to analyze it. Here's a transcription:

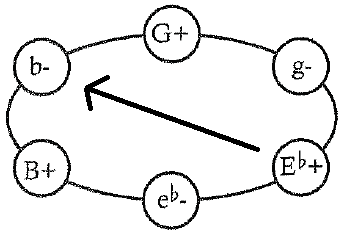

One of the first things I noticed was the change in key between the verse and chorus. The former seems to be in D major while the latter is in C major. What particularly captures my current attention is Robert DeLeo's bass line, which, by often playing the third and fifth of the tonic D major chord, constantly undermines any authoritative tonal conclusions about the verse. This is an example of what Mark Spicer calls a "fragile tonic", in which “the tonic chord is present but its hierarchical status is weakened." DeLeo's bass line is also what determines the BbMM7 chord (bVI in D) that appears near the end of each verse, differentiating that particular progression from the D minor chord that appears earlier in the same location. By altering the bass line, DeLeo also alters the progression, changing things up to keep a listener engaged. Even more fascinating is the harmony. That BbMM7 chord in the verses foreshadows the Bb that initiates the chorus. This time, however, because of the key change to C major, Bb is now bVII instead of bVI. While Bb moves to F in both the verse (bVI-bIII) and chorus (bVII-IV), in the verses that F proceeds to G (IV), while in the chorus it resolves to C (I). It's a great example of what I call "multifunctional harmony", where the same chords can function in different ways, even within the same song. Lastly, and most important, the harmony is also heavily chromatic. The intro riff and chords employ 10 of the 12 tones (only C# and G# are absent). While the progressions from F-C and C-G are extremely common, the move from Eb major to B minor is striking and most unusual. This is what Richard Cohn calls a "hexatonic pole" because it jumps across the hextonic cycle - in other words, it's as far away as you can get and still be in the same hexatonic cycle (Cohn, p. 18). Hexatonic poles are exceedingly rare in pop music - I cannot think of any examples. The closest I can think of is The Beatles' 'Michelle', which uses a similar but not identical progression from Eb6 (Eb-G-Bb-C) to B°7 (B-D-F-Ab). So 'Sour Girl' is, at least to my knowledge, the first pop song to employ a hexatonic pole.

REFERENCES Cohn, Richard. 2012. Audacious Euphony. Oxford University Press.

6 Comments

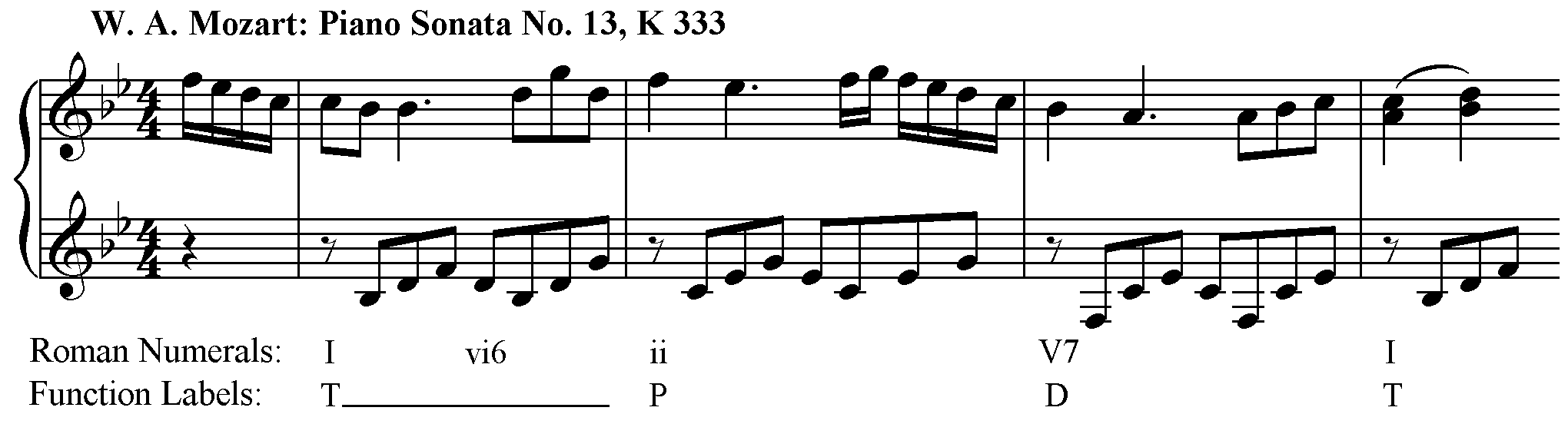

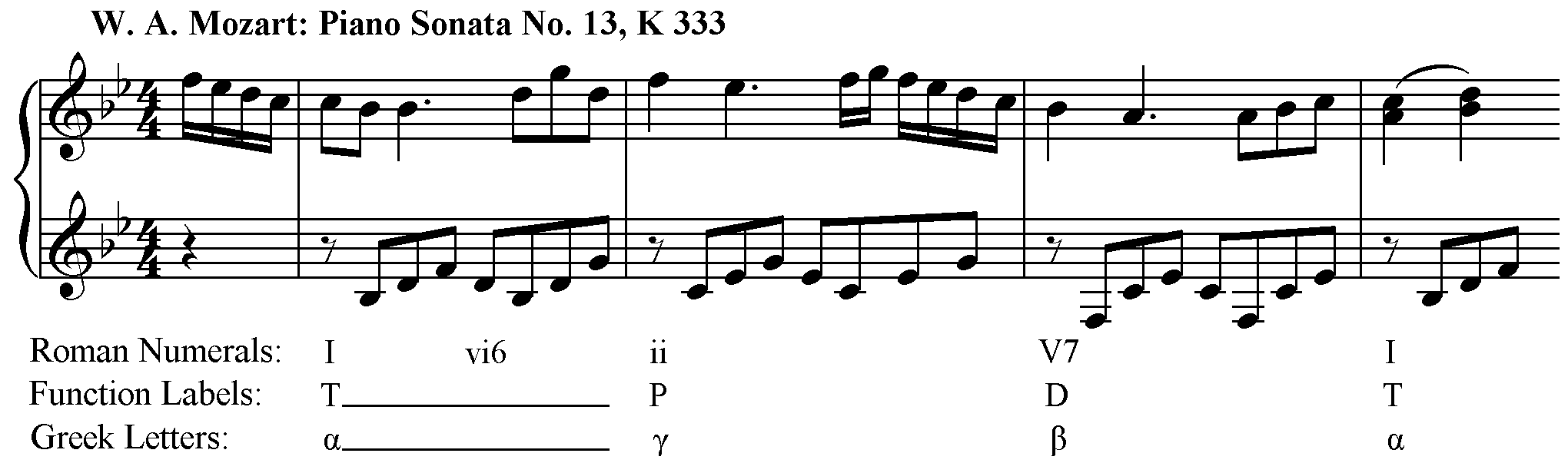

Common-practice functional harmony is predicated on the progression from predominant to dominant to tonic. In the below example of Mozart's Piano Sonata No. 13, those functions are abbreviated by their initial. Like classical harmony, pop harmony is also functional in the sense that certain chords lead to other chords, usually culminating in a cadence. However, unlike classical music, pop chords are subject to far less strict rules of progression. In other words, the progressions found in pop music are more flexible than those found in classical, with the same chords (or at least the same Roman Numerals) functioning in multiple ways. And that means any theory of popular music harmony must account for this multifunctional flexibility. Enter Christopher Doll. In his book Hearing Harmony (University of Michigan Press, 2017), Doll implements Greek letters to indicate distance from tonic:

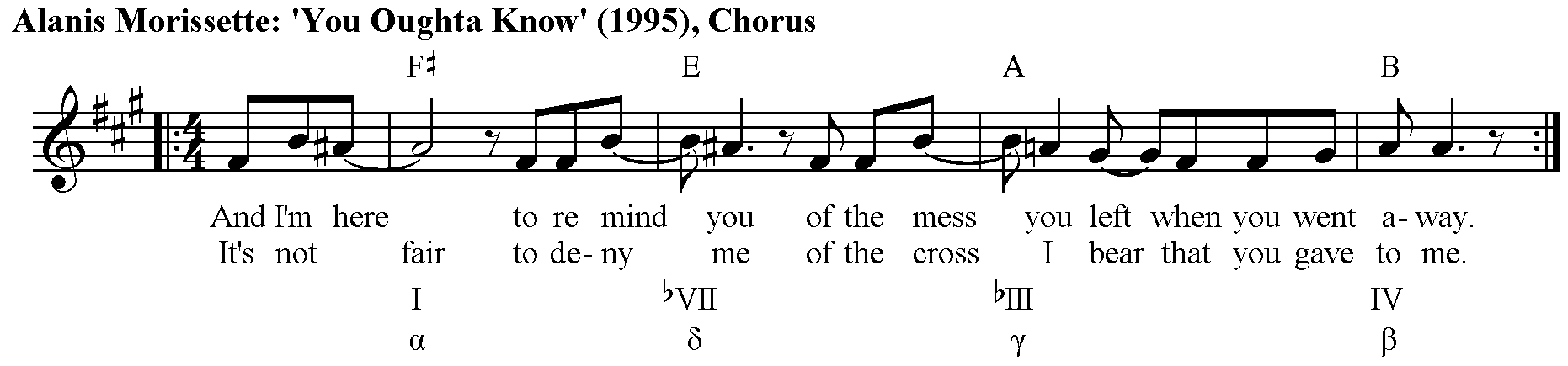

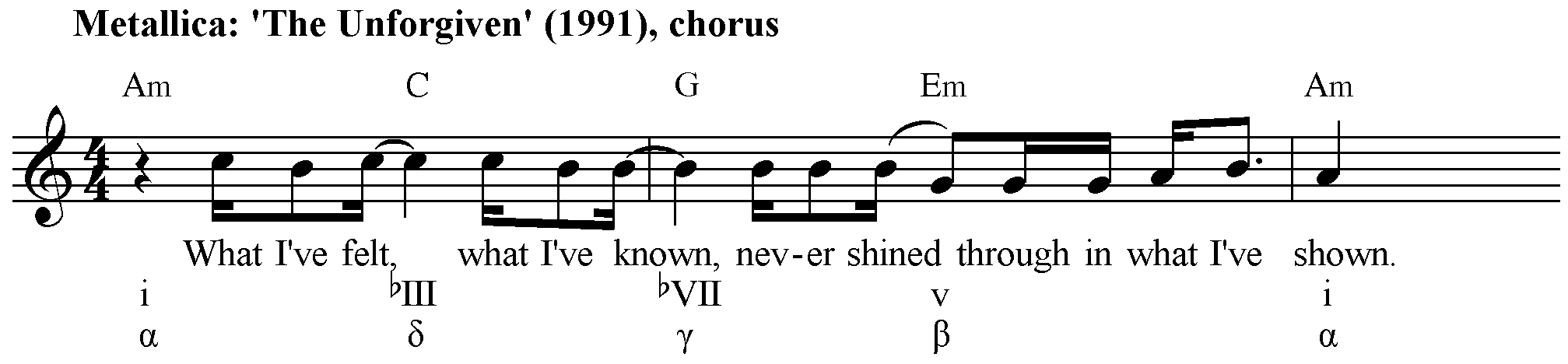

Doll goes into some depth in an appendix, specifying all possible chords in each of these functions and providing names like "hypo pre-subdominant (mediant of a subdominant)" and "medial pre-dominant (mediant of a dominant)". While I appreciate the thoroughness of his theorizing, I find the exhaustive details cumbersome to the point of being unusable in practice. But I find his notion of Greek letter functions quite compelling and practical. Applying Doll's Greek letters to the same Mozart example shown above yields the following: In this case, ii (c) functions as the predominant (γ), V7 (F7) as dominant (β), and I (Bb) as tonic (α). It's a straight-forward, textbook example. But what about a pop song, such as Alanis Morissette's 'You Oughta Know'? Here's the chorus from that song, which clearly employs functional chord progressions but in a rather different way from Mozart: In this case, IV (B) is the pretonic chord (β). It resolves to I (α) on the subsequent downbeat. bIII (A), then, is the pre-pretonic (γ); and bVII (E) the pre-prepretonic (δ). But that is just one example. What makes these Greek letter functions so compelling and useful is how flexible they are. The same chords can function in different ways depending on their syntactical order. Here is the chorus from Metallica's 'The Unforgiven', which incorporates similar chords but with different functions: This time i (a) is α, V (e) is β, bVII (G) is γ, and bIII (C) is δ. To avoid constantly scrolling up and down to compare the two songs, here are the Greek letter functions of both 'You Oughta Know' and 'The Unforgiven' side-by-side:

Tonic, whether major (I) or minor (i), will always be α - that will not change from one progression to another. But all other Greek functions are liable to change. Notice how β is IV in one song but V in the other. And how both bIII and bVII are γ in one but δ in the other. This is what I mean when I say pop harmony is multifunctional - the same chords can function in different ways. This is contrast to classical harmony, where chords typically function one way, and only one way. The value of Christopher Doll's Greek letter functional nomenclature, then, is that it addresses pop music's more flexible rules of progression - it illustrates the linear harmonic motion without the restrictive and loaded terminology of classical analysis.

In 1975, Pink Floyd released what I consider to be their best album, Wish You Were Here. The album consists of five tracks:

Despite its seven-and-a-half-minute length, 'Welcome to the Machine' employs only four chords: E minor, C major, A minor, and A major. Of those four, the A major might be the most curious because it is heard only once (during the second verse, at 4:18), where it substitutes for the A minor chord heard during the initial verse. The obvious question, then, is why? Why does the second verse use an A major chord where the first verse uses an A minor? What is the point of making that substitution? Before we can answer that question, we first need to progress to the next track.

Like its immediate predecessor, 'Have A Cigar' also uses only four chords: E minor, C major, D major, and G major. Notice that two of these four chords (E minor and C major) were used in 'Machine', while the other two (D major and G major) were not.

So we have seen how 'Machine' uses the chords E minor, C major, A minor, and A major, and how 'Cigar' uses E minor, C major, D major, and G major. Now, given the title of this blog, can you make an educated guess regarding what chords are used in the title track? I'll give you a hint: There are six of them. Those six chords are E minor, C major, A minor, A major, D major, and G major. They should be very familiar since they are the combined harmonies from the two previous tracks - no more, no less. This is what I mean by the term "chordal accretion". Here's the same concept using color-coded mathematical symbols: The chords of 'Welcome to the Machine' (E minor, C major, A minor, A major) + The chords of 'Have A Cigar' (E minor, C major, D major, G major) = The chords of 'Wish You Were Here' (E minor, C major, A minor, A major, D major, G major)

So, getting back to that curious A major chord in 'Welcome to the Machine', the reason it's an A major in the second verse instead of A minor is to help set up this chordal accretion process, which culminates in the focal point of the entire album, the title track.

|

Aaron Krerowicz, pop music scholarAn informal but highly analytic study of popular music. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed